Presented by the C.N. Gorman Museum

Feathered Relations originated at the C.N. Gorman Museum at UC Davis. This online exhibition is brought to you in partnership with Exhibit Envoy.

Introduction

This exhibition is about relationships: relationships to the land, to cultural knowledge, and to the nonhuman beings that we share space with. Our feathered relatives are important to our environment. They have specific names, and they have a certain role within our cultures. I’m honoring them, and thinking about those cultural stories that go with them through the Navajo way.

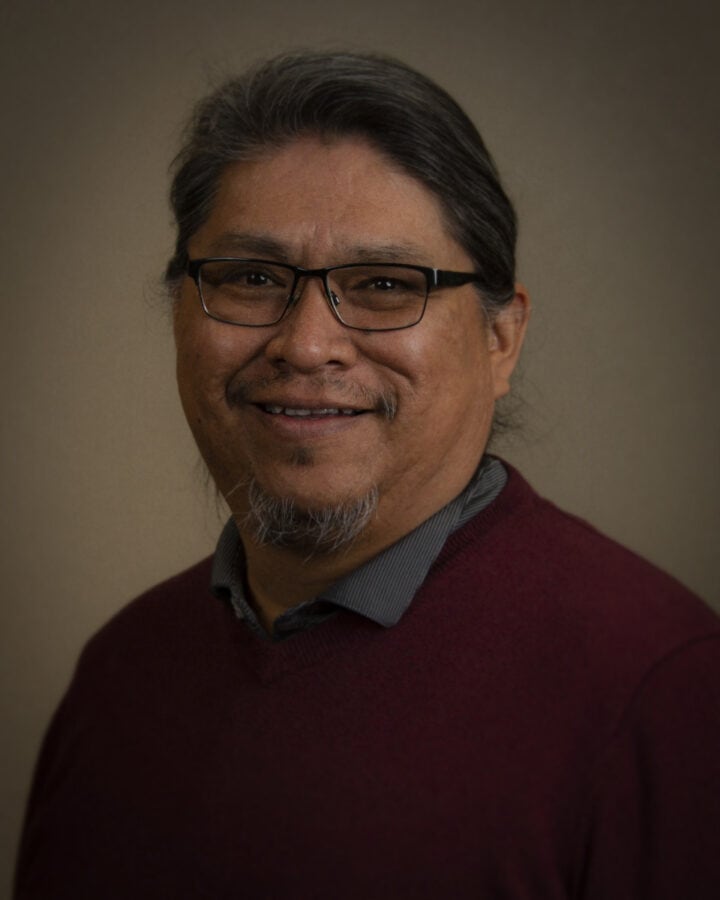

Marwin Begaye

Welcome to Feathered Relations: Works by Marwin Begaye.

Growing up in New Mexico, Marwin Begaye began drawing and creating at a young age, inspired to become a printmaker by the long line of silversmiths and rug weavers from whom he descends. The influences of his family, his Navajo heritage, and shared cultural knowledge and stories are evident throughout this exhibition, coming together within his works. Begaye’s intricate compositions serve as a way for him to share and remember place, remember stories, and remember songs.

As you view this exhibition, take time to connect with the birds and patterns in each piece; look carefully and see what comes to you about your own relationships with birds, nature, and the living things all around us.

Navigating the Online Exhibit

As you peruse this exhibit, you’ll be able to look closer at each print, and the detail within it. To view a larger version of each image, simply click or tap on the work.

Artist Statement

Birds are about our relationships – to nature, to one another, to culture. In a way, they provide a link back to the landscape. They connect the sky to the earth and through their natural patterns of migration and annual nesting cycles, they connect us to place.

This connection to place and nature is a stark contrast to our social concepts of “staying connected.” In the digital age, we are virtually connected to one another though increasingly disconnected from nature. The birds are a link back to nature.

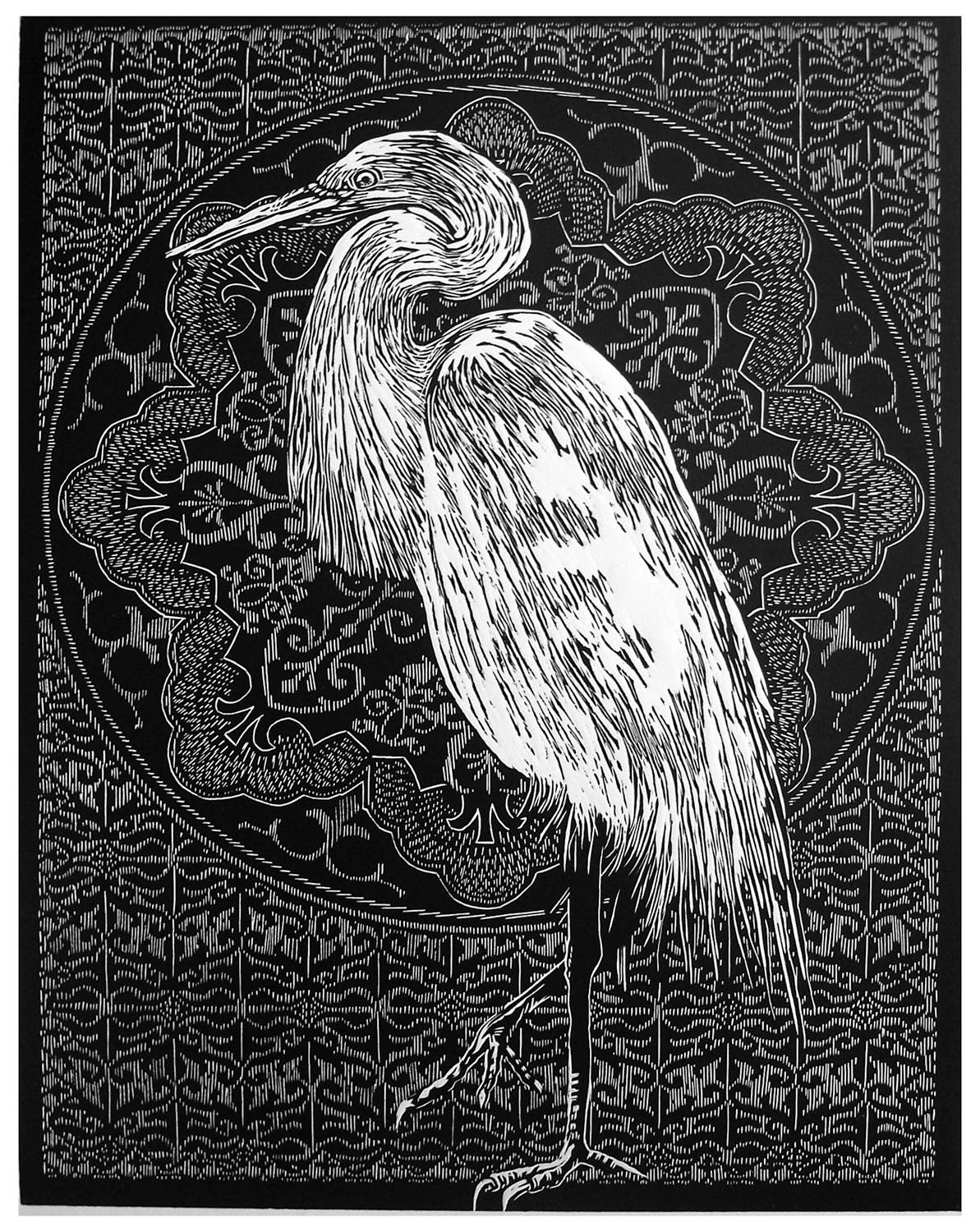

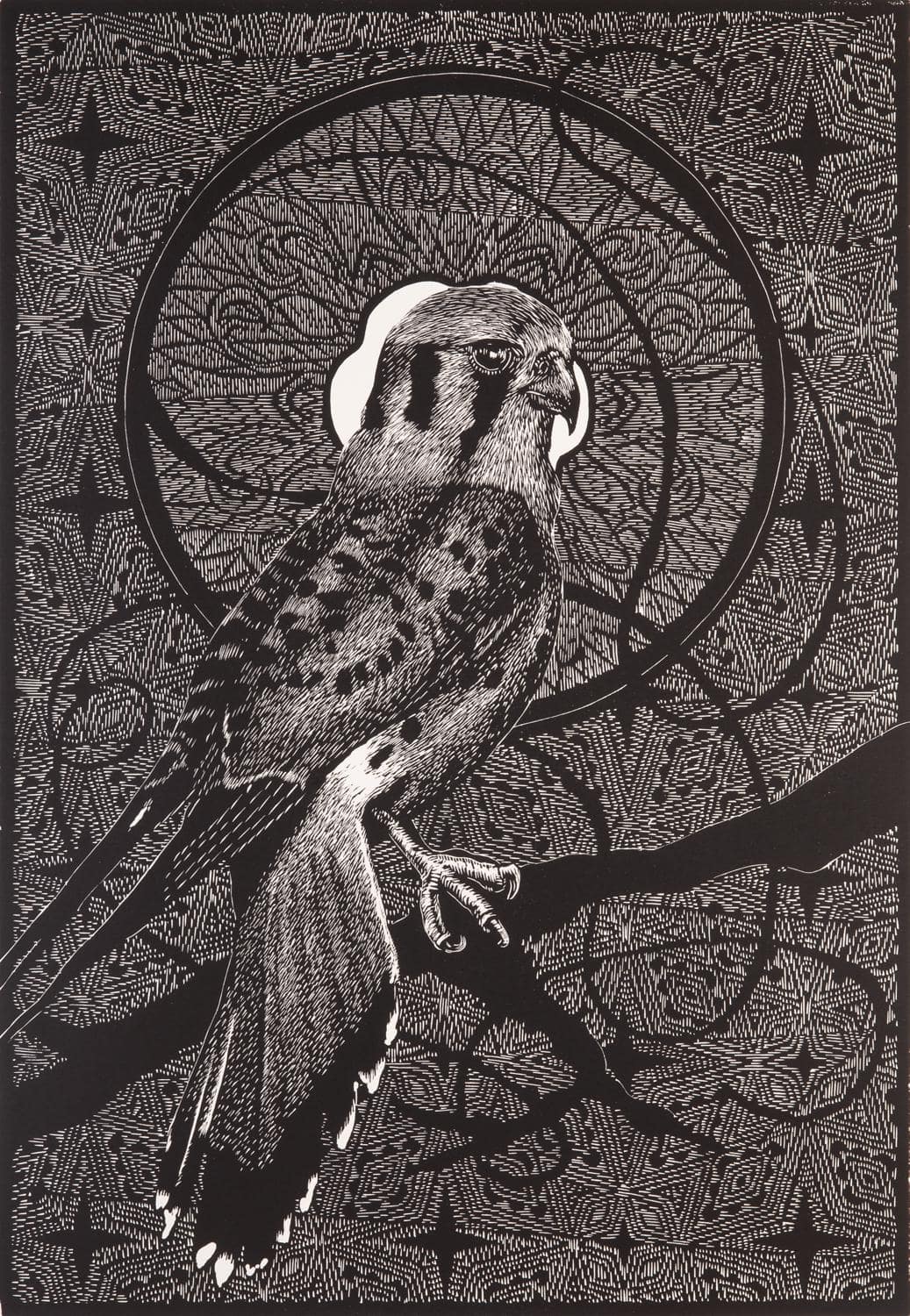

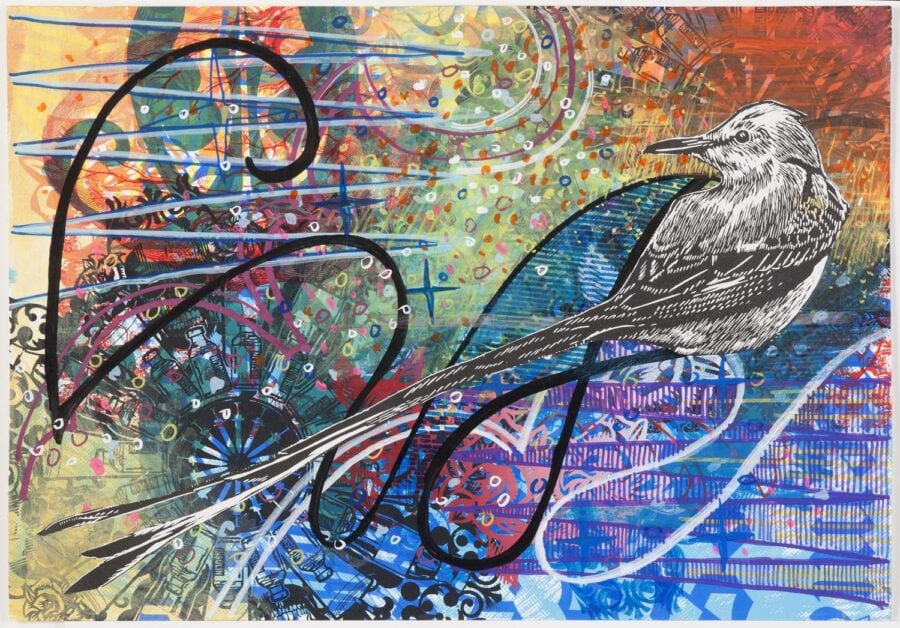

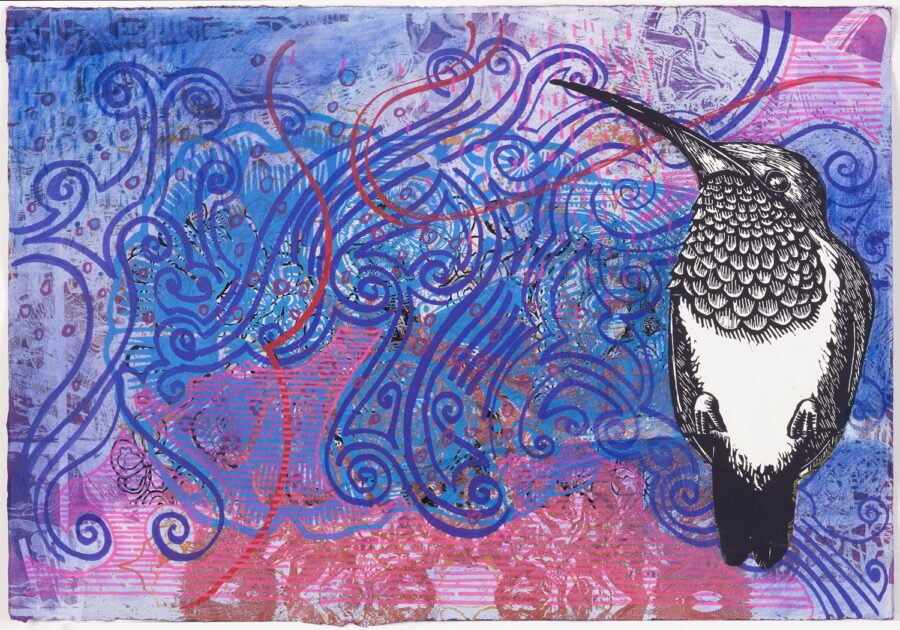

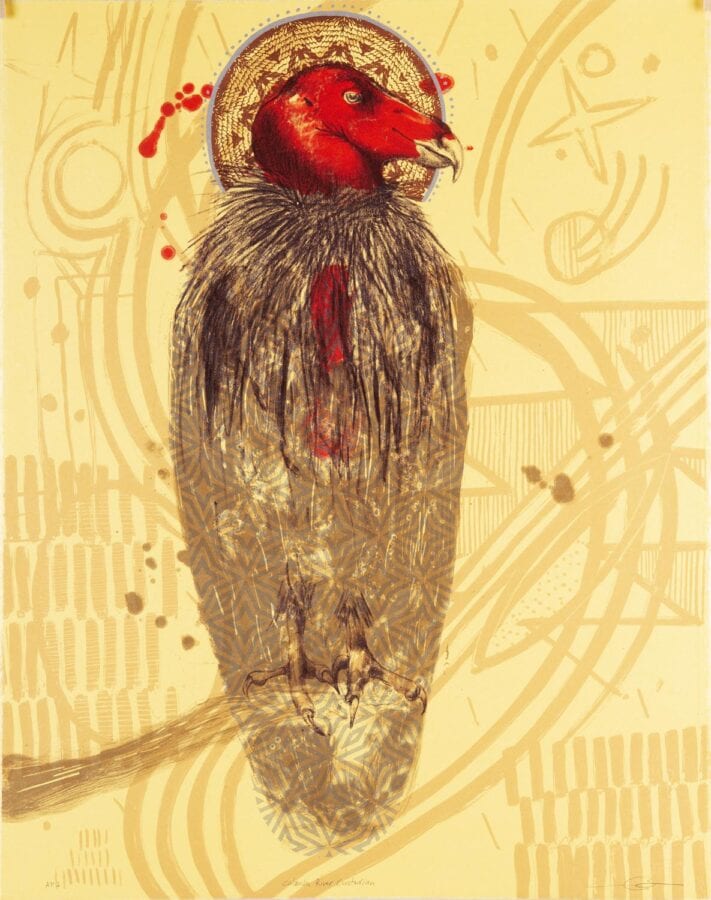

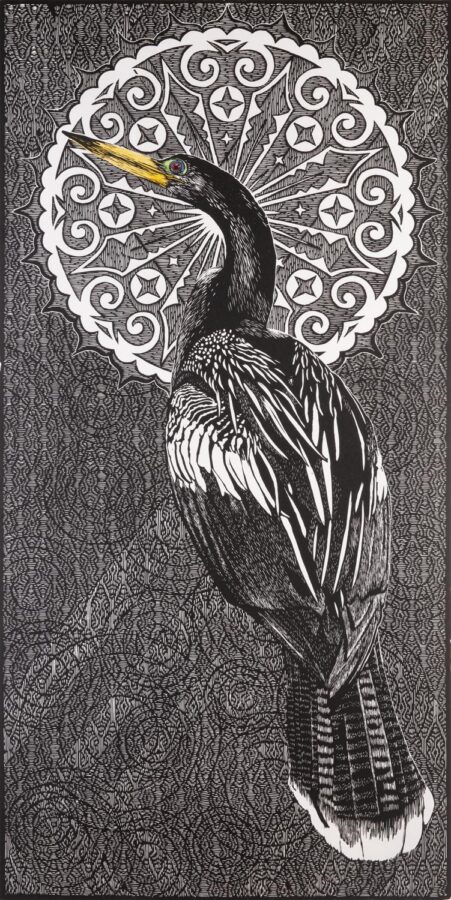

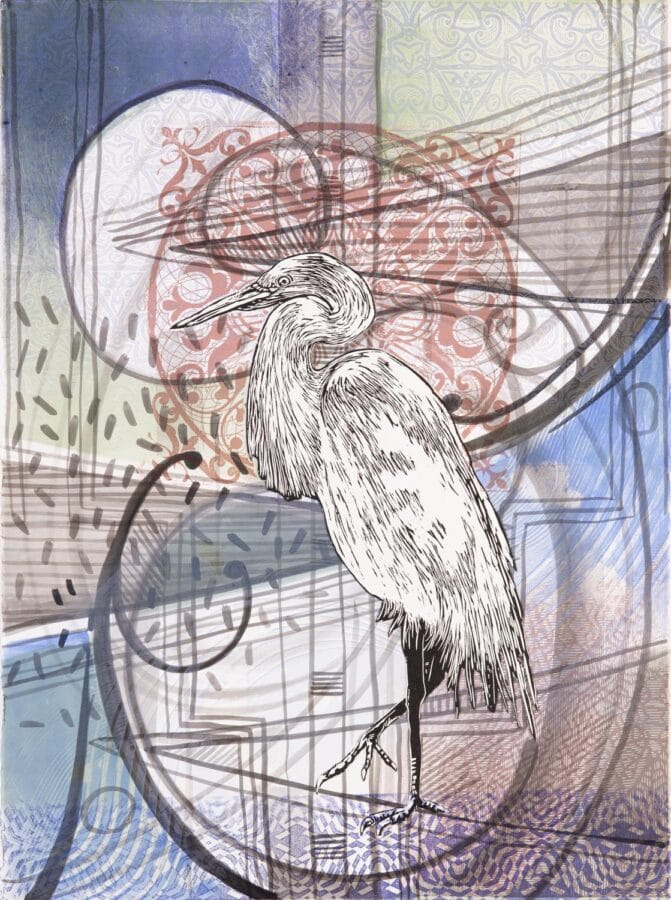

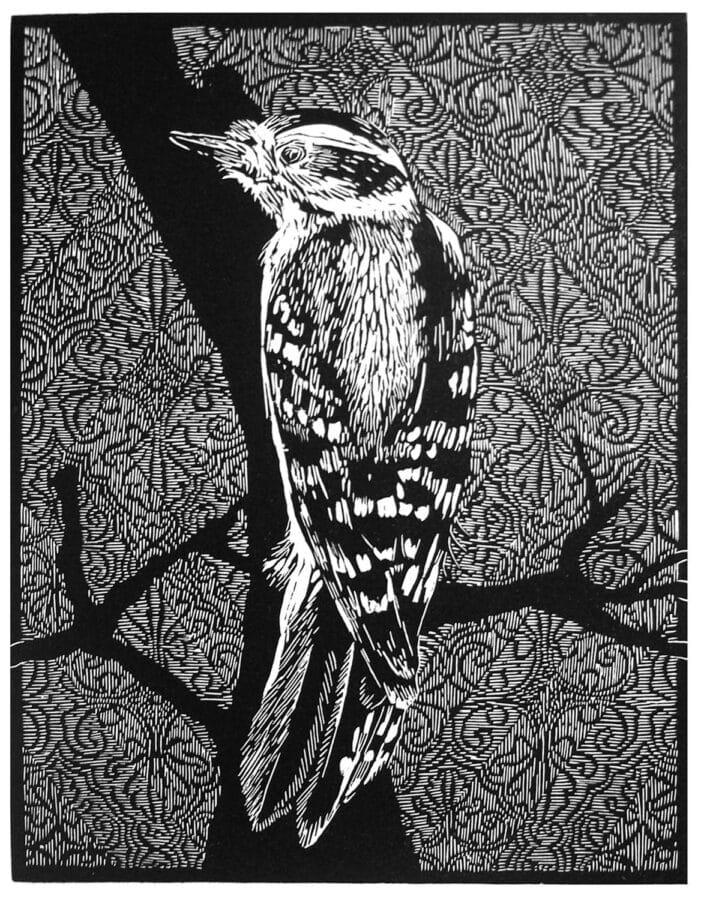

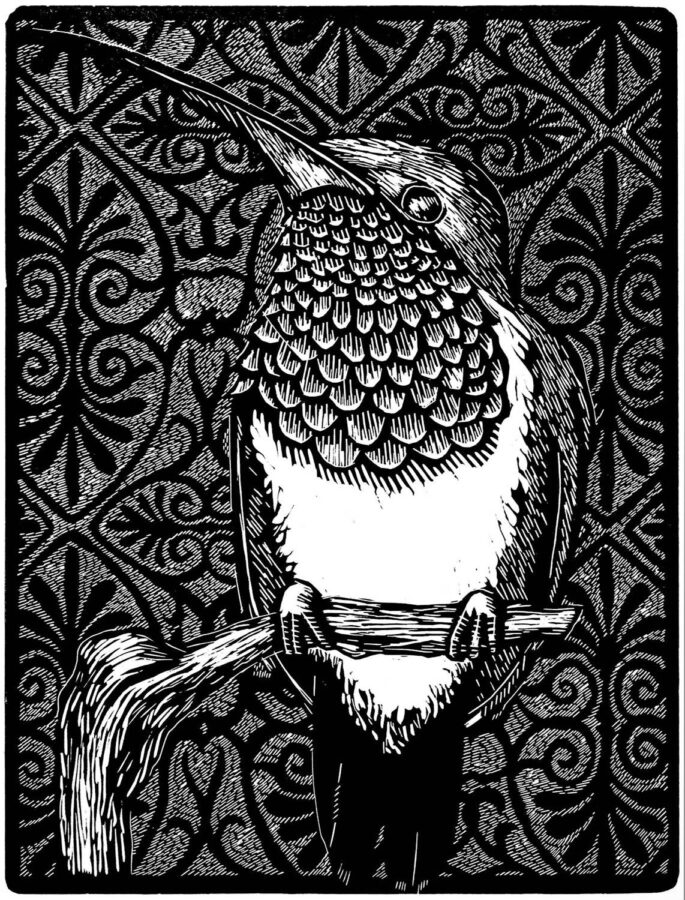

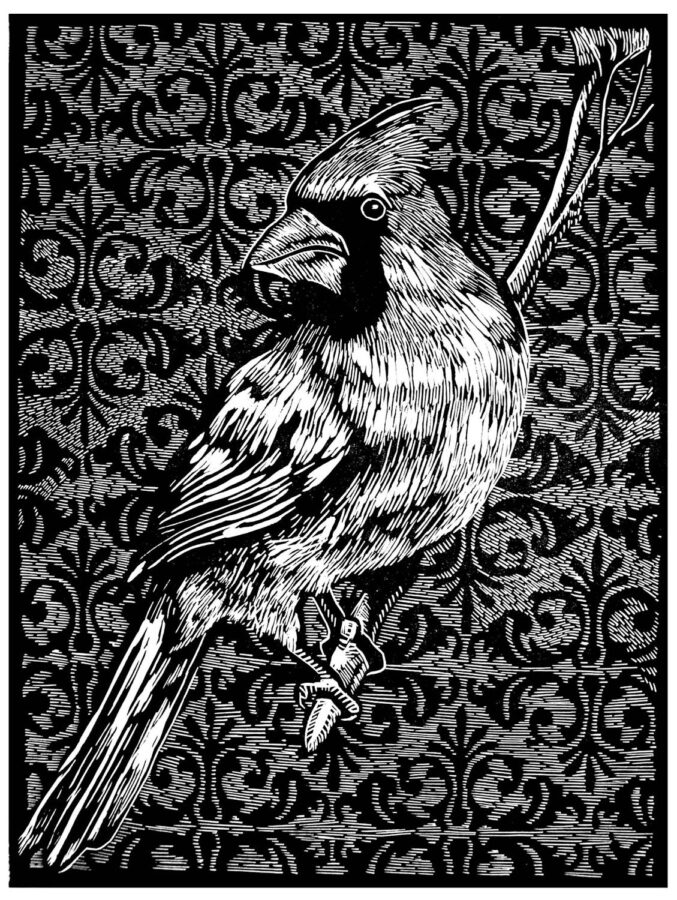

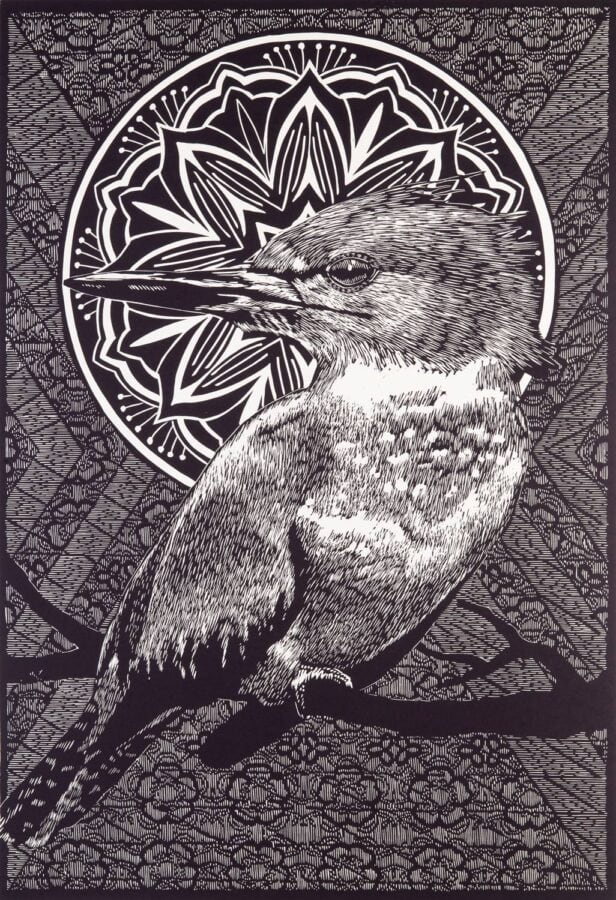

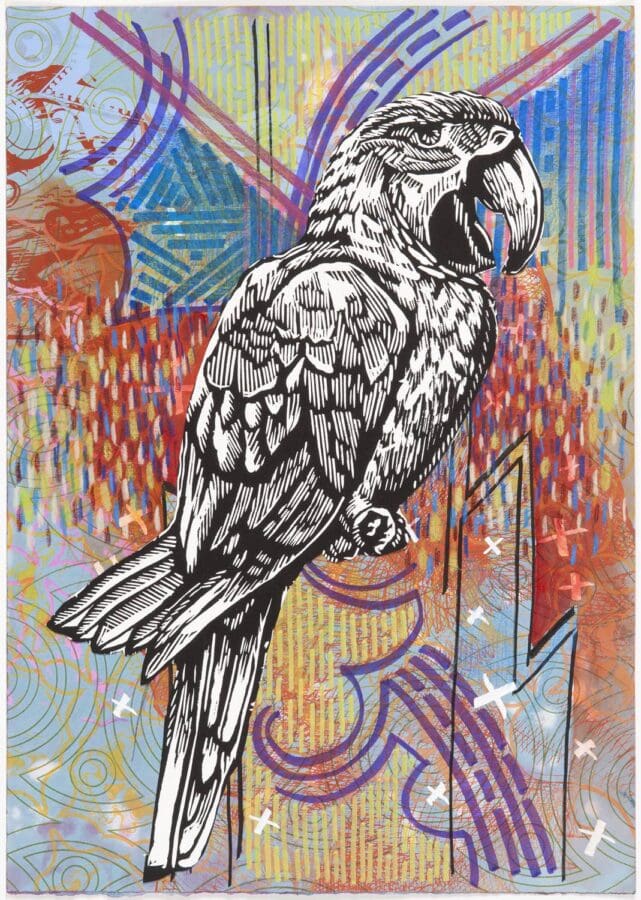

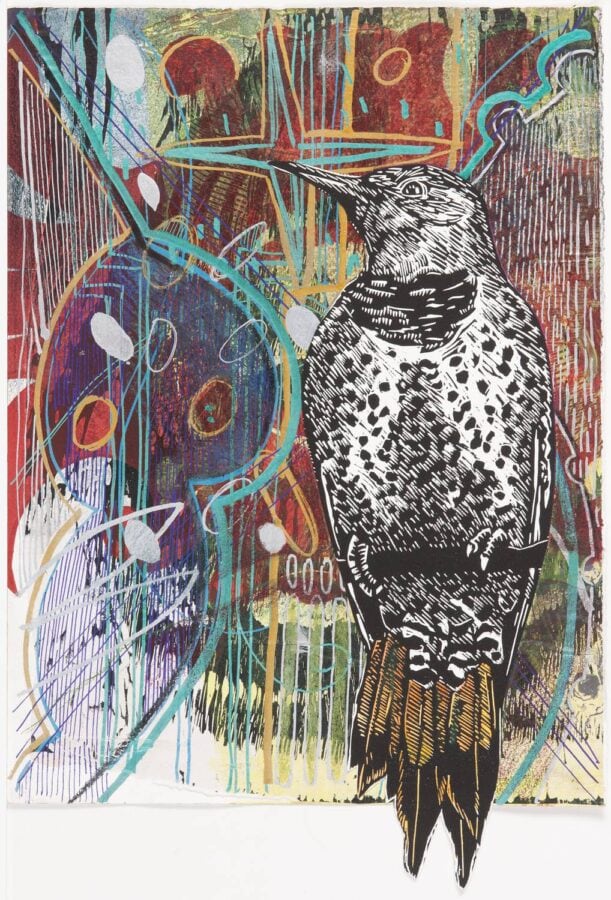

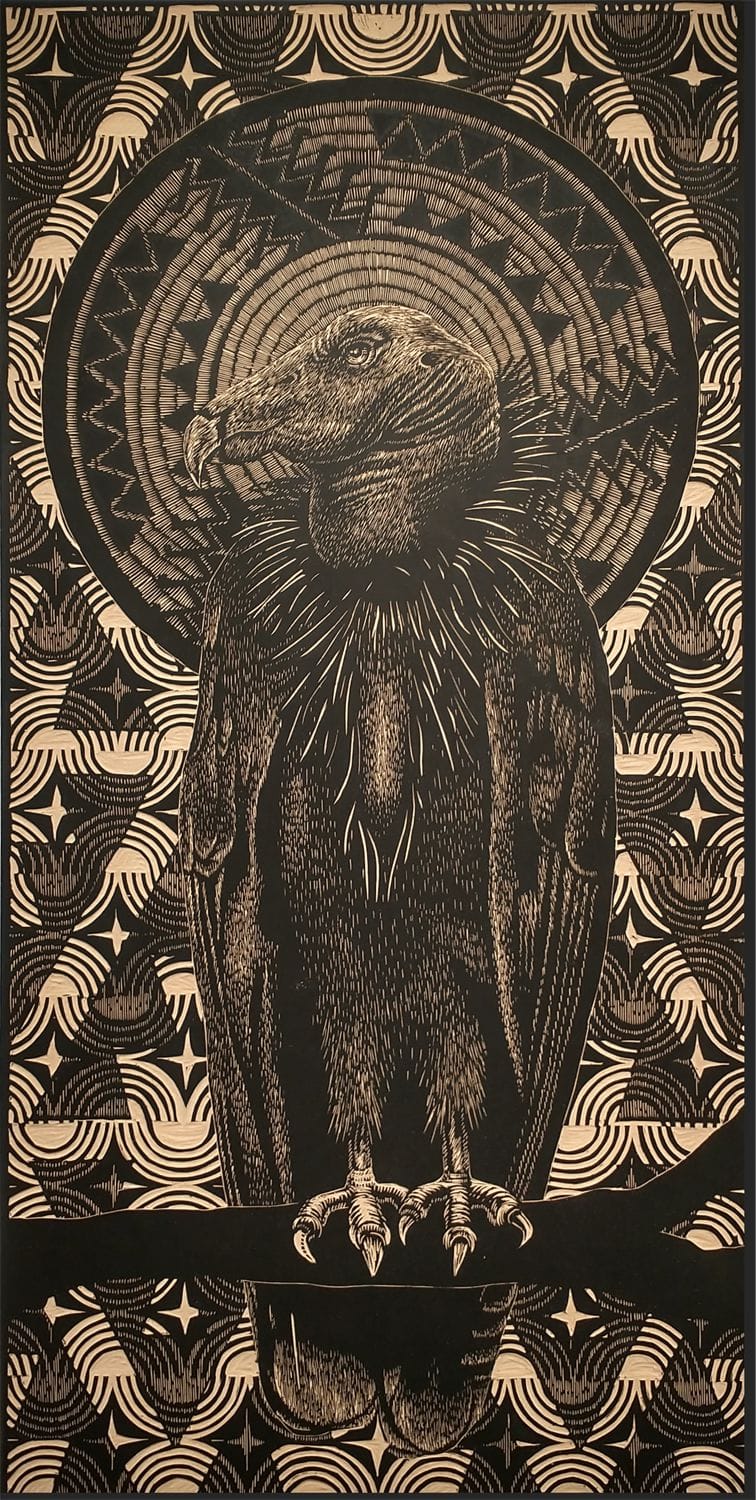

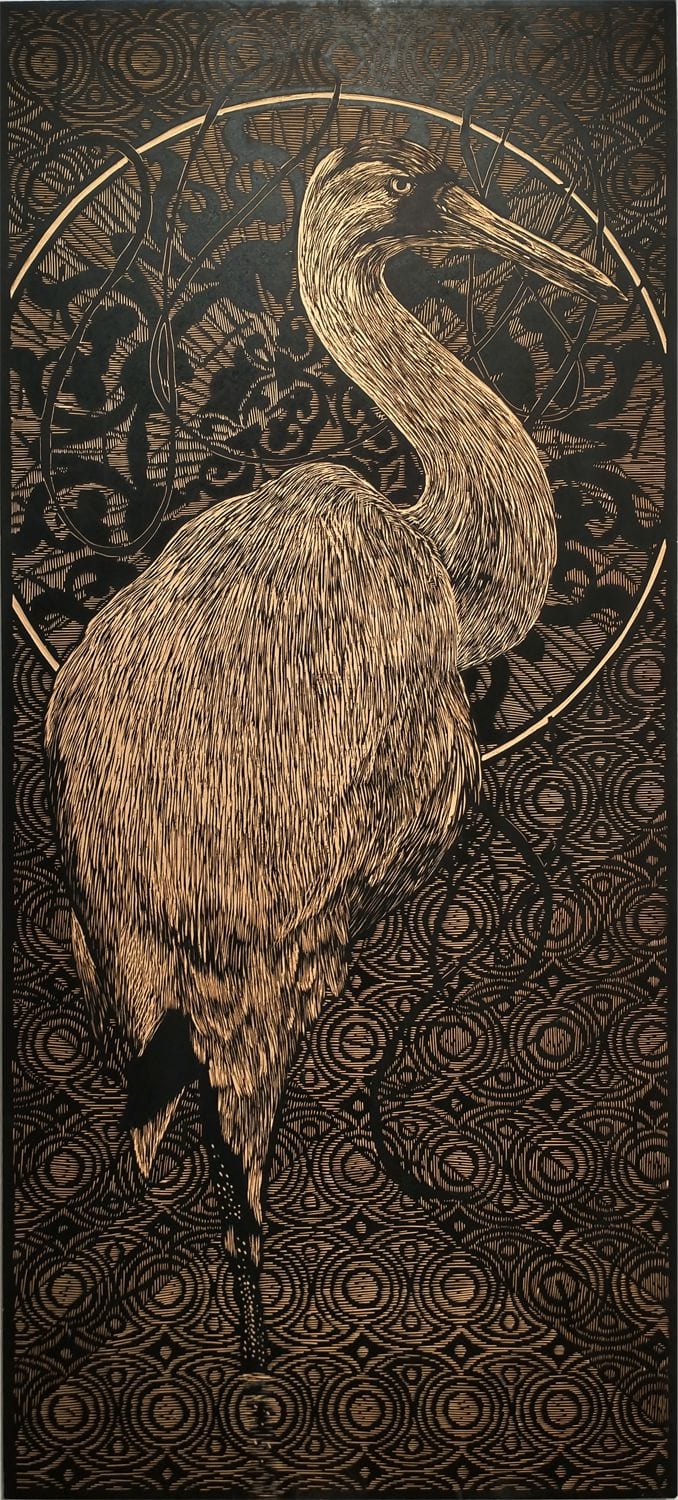

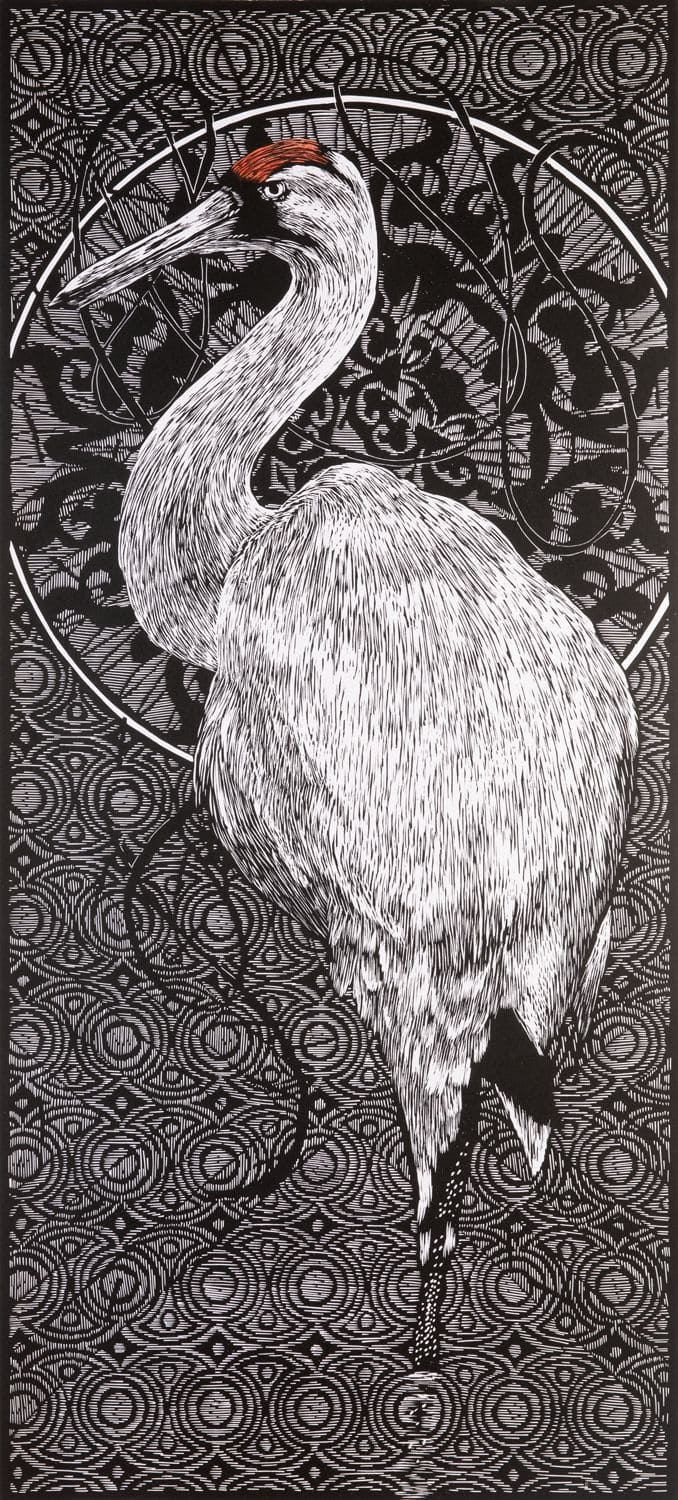

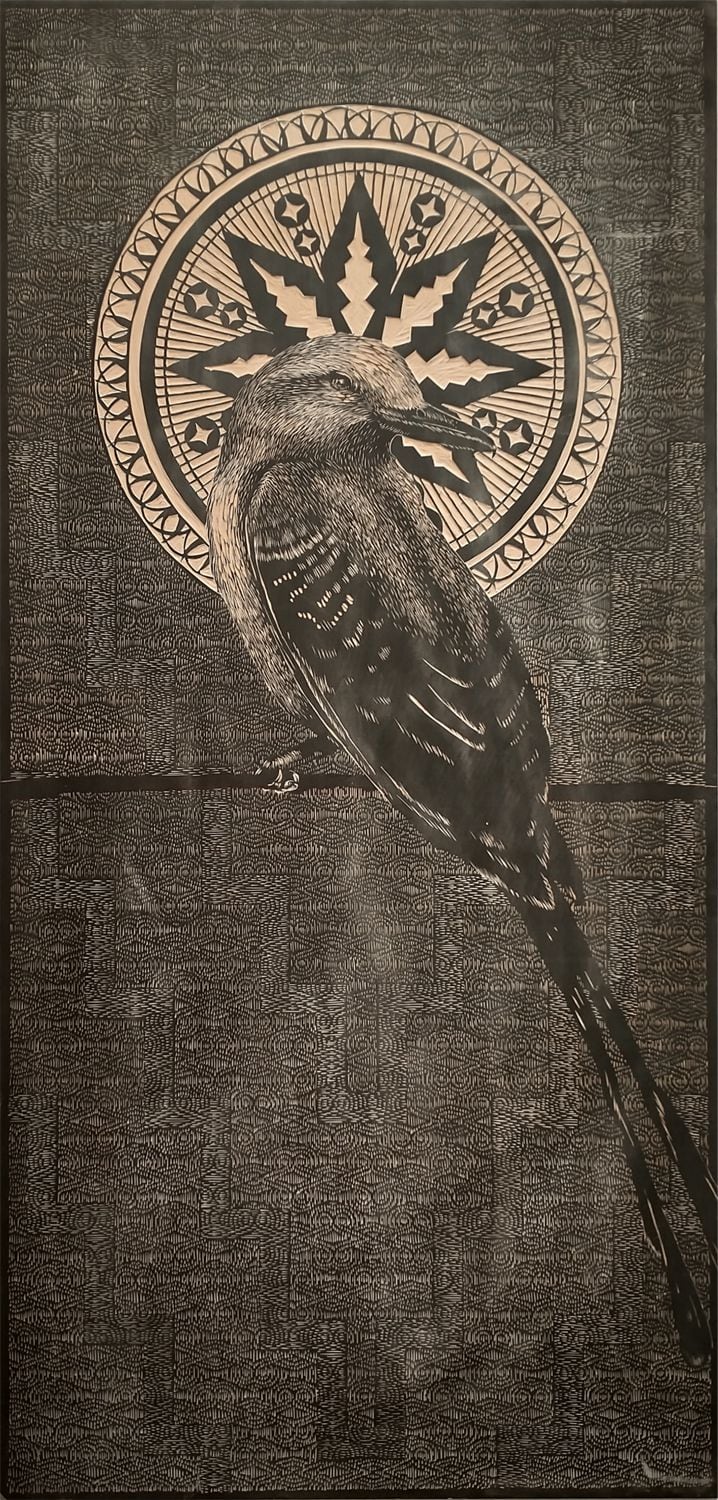

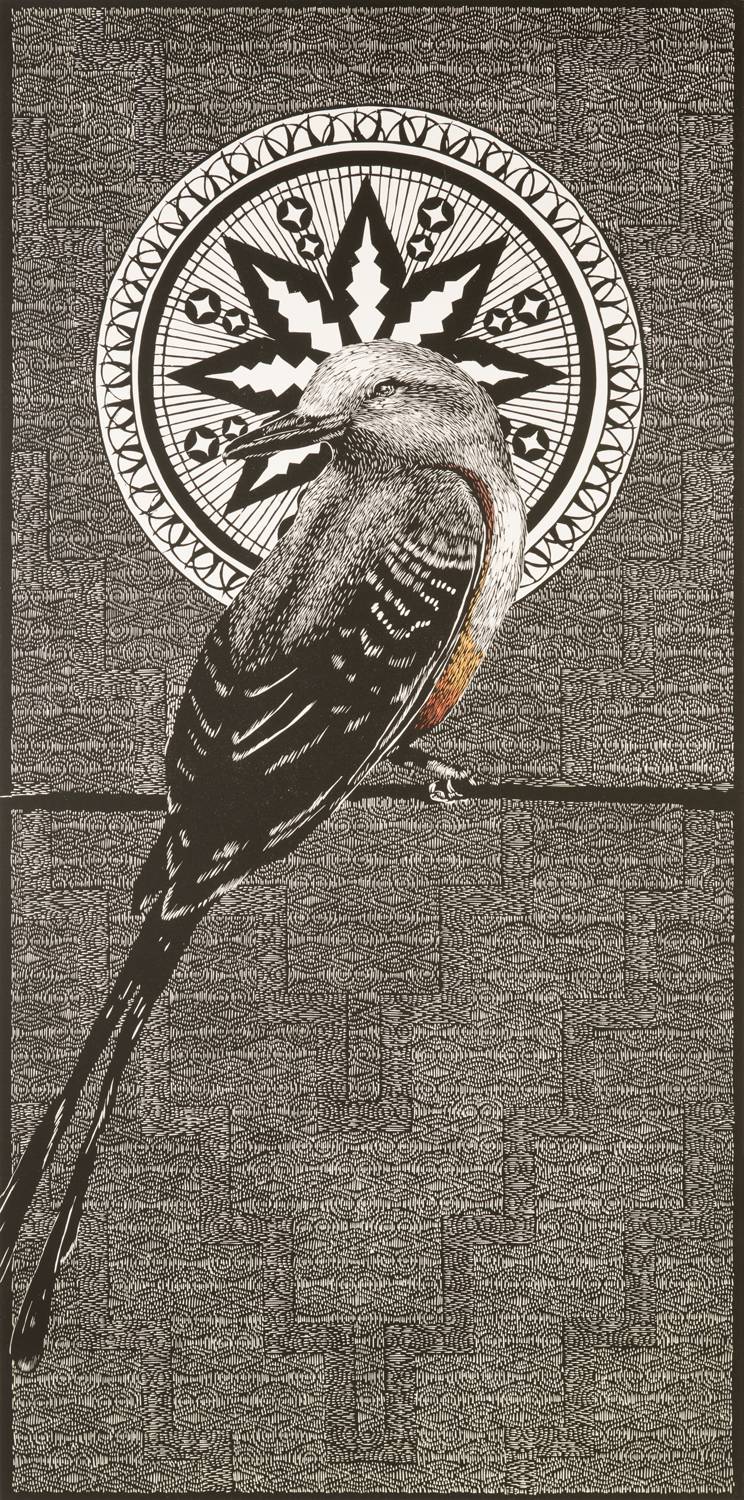

I honor the birds by giving them halos, and the marks often associated with sacredness, because in our beliefs, the birds have powers for healing and for ceremony. The birds carry these power, shared with us through the gift of their feathers. The birds are sacred.

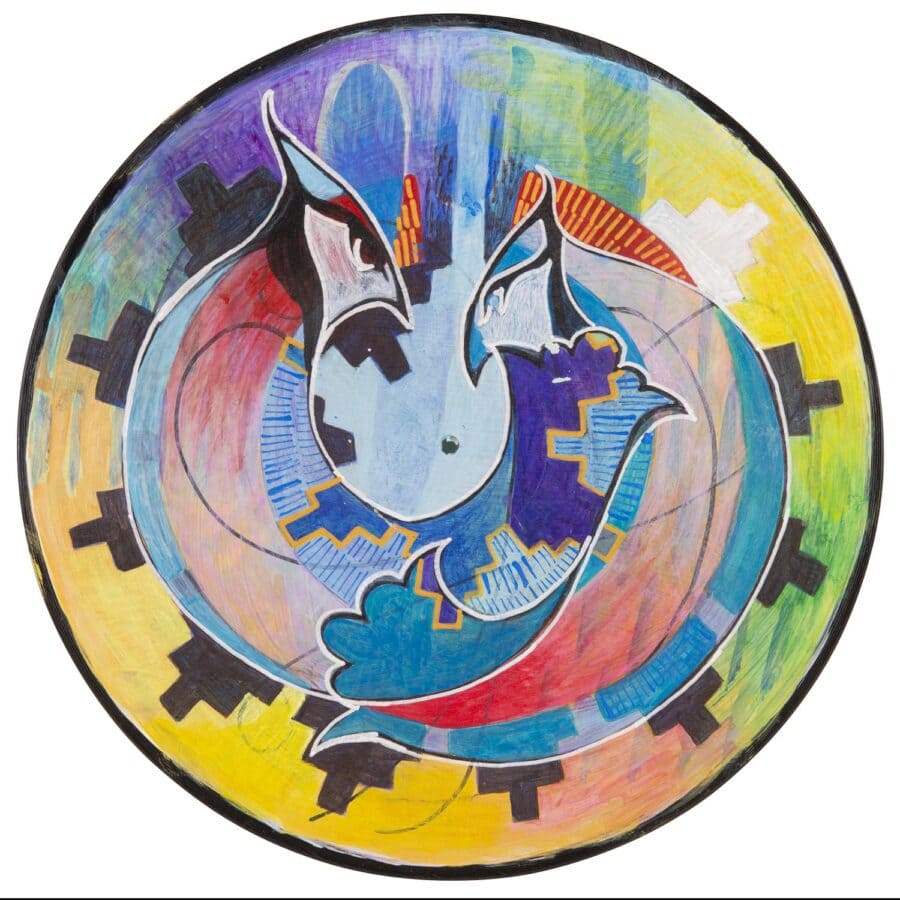

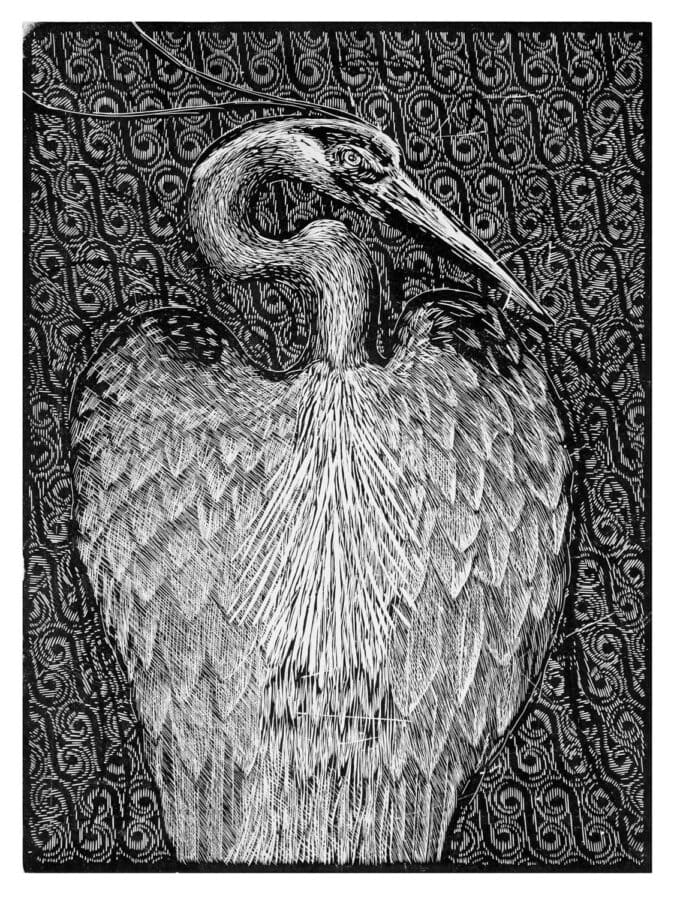

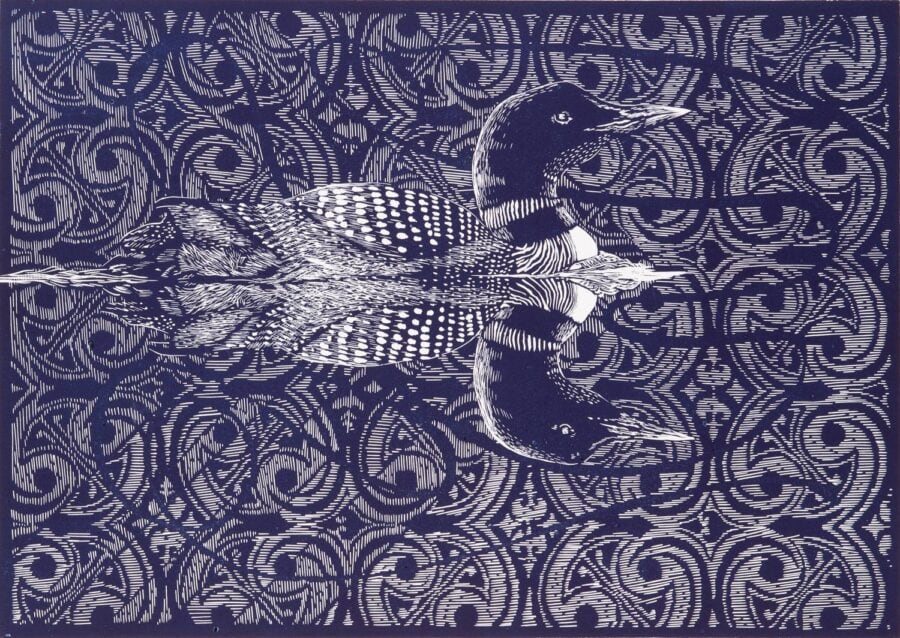

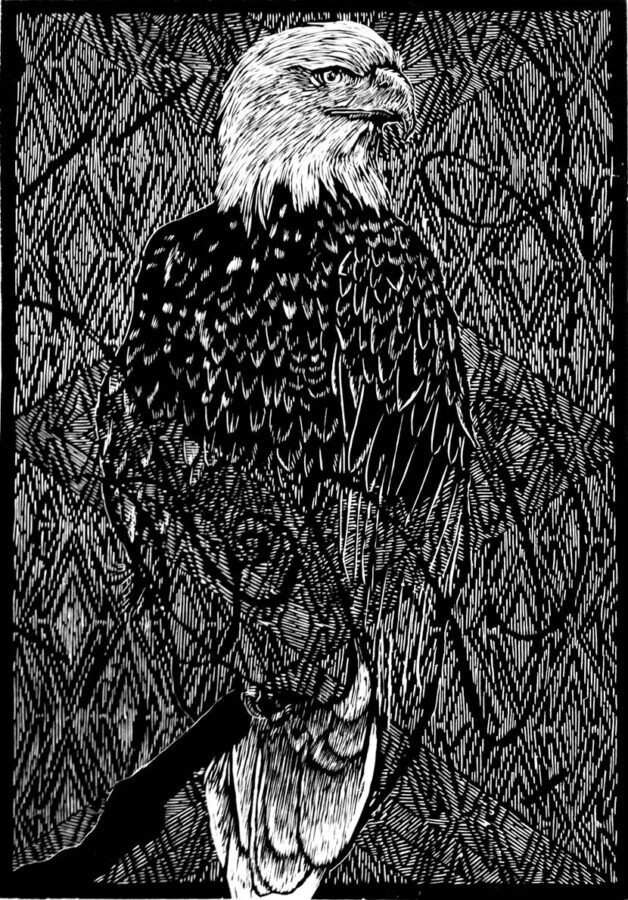

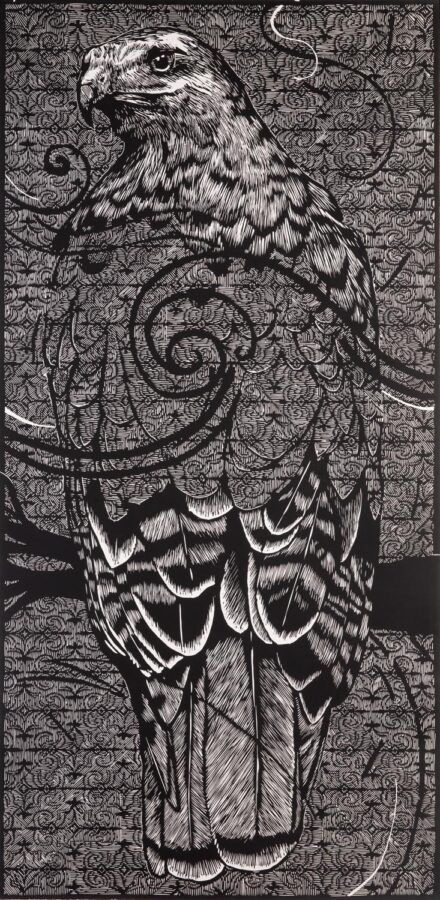

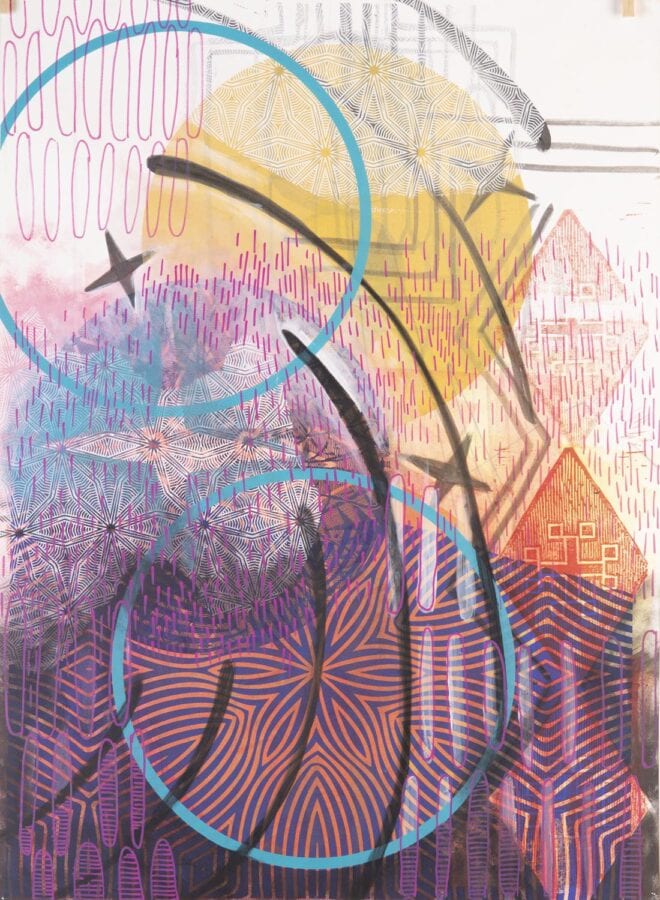

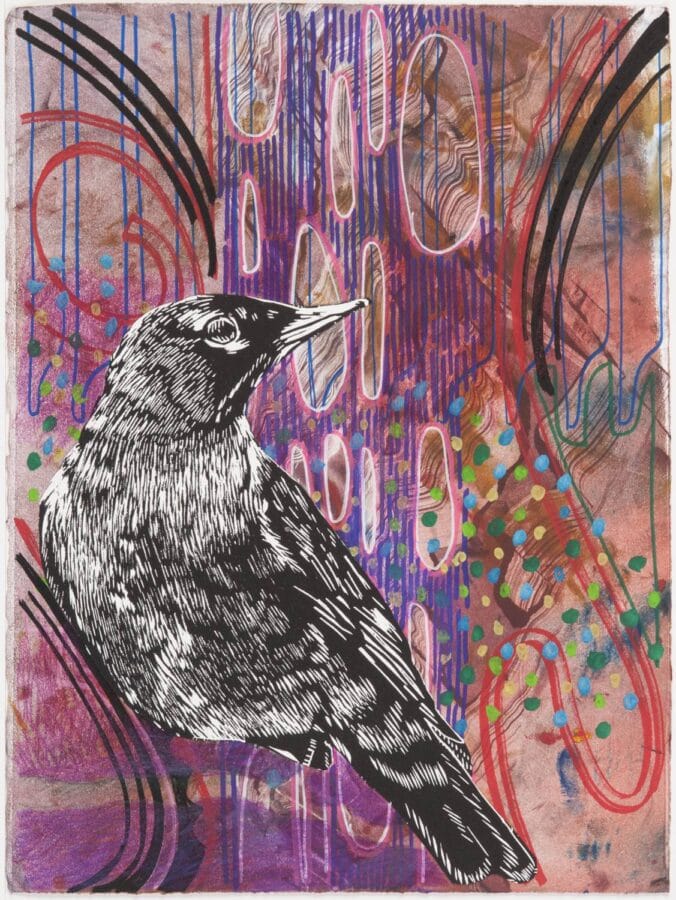

Their distinctive forms, each has its own crest and body shape, allow me to elaborate through relief printing and the gestural mark the beautiful simplicity of their line. The linear structure of their feathers allows me to activate the composition by using directional marks, whether paint or woodblock cuts.

I am interested in the combination of a conceptual homage to the birds with my development of aesthetically graceful compositions. It is very satisfying when collectors offer their own connections to the birds as a supplement to the stories shared through these images.

– Marwin Begaye, 2020

Marwin Begaye (Navajo) is an internationally exhibited printmaker, painter and nationally recognized graphic designer. As Associate Professor of Painting and Printmaking at the University of Oklahoma’s School of Visual Arts, his research has been concentrated on issues of cultural identity, especially the intersection of traditional American Indian culture and pop culture. He also has conducted research in the technical aspects of relief printing and the use of mixed-media.

His work has been exhibited nationally across the U.S. and internationally in New Zealand, Argentina, Paraguay, Italy, Siberia and Estonia. He has received numerous awards, including the Oklahoma Visual Artists Coalition Fellowship, First Place at the Red Earth Festival and Best in Category in Contemporary Painting at the Gallup Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial Best of Category in Graphics at 2015 Santa Fe Indian Market, and Best of Show in Painting/Drawing/Graphics/Photography at 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market. He has been featured in many publications and is represented by Exhibit C in Oklahoma City.

Curatorial Statement

Living in the Sacramento Valley, I am able to witness and experience the annual migration of millions of birds on the Pacific Flyway who make their winter home in local seasonal marshes. It is always a welcome sight when the Tundra Swans return and geese fly high overhead in their chevrons, hearing their calls. These seasonal visitors add to the population of year-round bird residents.

Every day there are visitors – the hummingbirds in our garden each morning, owls in the nearby trees hooting at night, white cranes taking over whole trees and fields, herons that line the waterways, wild turkeys that roam the neighborhood, and massive flocks of crows that congregate each night as I leave work. Often it feels they are visiting and greeting us, while at other times we are out and visiting them, but mostly it seems we are simply living together in the same environment as we get on with our day. Their presence is both of awe and beauty, as well as respect for their resilience and survival. Their visits foster reassurance and warmth for which I am thankful to experience.

Marwin Begaye’s works in this series create a moment of pause, a stillness in which to experience this mutual encounter. Each work focuses on a single bird, rendered in extraordinary detail set in a halo of Indigenous design and on a background of ornate geometric patterning. The scale of many of the prints being over four feet tall enhances their presence and entices the viewer to come closer to see the fine articulation of the artist’s designs.

Equally engaging as the prints are the actual woodblocks from which they were created. Laser and hand cut, the large blocks are exhibited alongside their mirrored print giving perspective to the complexity of the artist process. The growing series includes birds from across the continent and beyond placed in backgrounds that evoke a sense of migration and movement that can even reach to the stars.

The exhibition debuted at the C.N. Gorman Museum at UC Davis just before the pandemic and we are grateful to Marwin Begaye and Exhibits Envoy to share it with you in this virtual format.

– Veronica Passalacqua, Curator

Veronica Passalacqua is Curator at the C.N. Gorman Museum, University of California, Davis. As a writer, curator, and scholar of Native North American art, her research focus is contemporary Native American art with an emphasis in Native American photography. She has curated exhibitions nationally and internationally including the Autry National Center, Pitt Rivers Museum, Navajo Nation Museum, and Barbican Art Gallery. She recently published the anthology, Native Art Now!: Developments in Contemporary Native American Art since 1992 (2017).

For the Winged Ones

By Miranda Belarde-Lewis (Zuni/Tlingit)

The birds knew something was happening. They were observing change.

Marwin Begaye

When I was a little girl I used to wake up to mockingbird songs. I can still hear the long high note that started it off, dipping down into the melodic sing-songey four notes that followed. Over and over the mockingbirds sang their song. For a while during my surly teen years their song got on my nerves. “Don’t they know any other song – jeez!” And now, thirty some years later, I can’t get their song out of my head: I wish I could wake up to their sweet little tune.

Marwin and I grew up less than 30 minutes from each other in west central New Mexico and I’m willing to bet he grew up hearing the same song. The birds move freely between Zuni Pueblo and the area outside of Jones Ranch where Marwin spent his childhood. The birds travel well beyond our little section of the world to wherever birds go.

The high-desert/plateau landscape of western New Mexico is not the harshest desert in the southwest by any means, but it does require a deep respect of the land, water, animals and seasons in order to survive, let alone to thrive for millenia, as both Marwin and my respective ancestors have done. Survival for thousands of years requires careful observation of one’s environment and surroundings and has influenced every aspect of our aesthetics; the richly layered textures, the subdued color palette of the desert floor, the intense fiery sunsets all show up in our pottery, weavings, baskets, and paintings.

The interdependence of plant people, animal people, insect people, winged people and human people forms the basis of most Native and Indigenous epistemologies. Our philosophies instill values about what it means to be human in this world. Our languages reflect our kin and how we assign levels of respect and reverence based on our closeness and proximity to various entities, both human and non-human.

Both our respective communities use feathers in ceremony. I grew up watching the men in our family carefully lash different types of feathers to wooden sticks several times a year. My father explained the feathers carry our prayers, blessings and aspirations to our ancestors and to our spiritual helpers. My uncle explained the feathers were from birds associated with the six directions. Each time I’ve witnessed family members making their prayer sticks, I appreciate their attention, their focus. That focus is evident in Marwin’s process, especially for the massive wood block prints. Deciding on the story each print will tell, meticulous mapping of the negative and positive areas, and sharpening the knives – this routine requires patience and a plan, one of the hallmarks of Indigenous peoples.

The hyper technological, instant-gratification world we live in demands our attention at every moment, whittling away at our patience and our attention spans. The glowing connections to a global network regularly bring us news and information that has immense impact. In September 2019 my pocket-sized rabbit hole informed me that scientists discovered three billion birds had vanished from North America since the 1970s. Three. Billion. Birds. This news hit me like a punch in the stomach. It has to be a humbling realization for Marwin to know that his images of birds will likely become an entry in the historical record, documenting the birds that used to be part of our lives.

In a media driven world, a message has to be able to compete with all the noise on the web and the noise in our lives. Marwin’s layered homage to birds is subtle, communicated through the calm, gentle manner of speaking typical of our shared territories. These images are a departure from his earlier activist-based work; the birds, the backgrounds and the striking detail are rendered mostly in blacks and whites with dazzling backgrounds that boggle the mind but require intense observation.

To the unschooled eye, one might ask how these prints and paintings are “Native art.” Forget the argument that they are Native art because Marwin is Navajo. If we’re searching for loud and obvious visual indicators but are not paying attention, it would be easy to miss the details that document not only the highly detailed physiological renderings of the birds, but the quiet nods to Marwin’s Navajo heritage and to the original peoples of this continent. There are textile and basket designs incorporated into the backgrounds that reflect Diné sensibilities; the halos on certain birds indicate their status as holy beings connected to the divine in Navajo culture; he also incorporated tribally specific designs that surround the Condor of his grandchildren’s inherited territories of California.

In many ways Marwin is challenging us all with these images. He is quietly asking us to pay more attention to our surroundings. The messages he’s communicating through his pieces encourage us to look beyond the process of how he made the pieces. Artists who create at this level are repeatedly asked, and will continue to be asked, basic questions about process. The constant surface level inquiries about how Native master artists like Marwin create what they create are tinged with a mixture of curiosity and incredulity, as if these creative, hardworking perfectionists could not possibly have created these works. The needling technical questions solely focused on how to create multi-media works, lithographs, monotypes and woodblock prints do nothing to help that type of viewer begin to understand the abundant facets of Marwin’s work. And maybe that’s okay. Maybe the deeper meaning is not for them, but for us.

The images in “Feathered Relations” reveal to us that in addition to being a husband, dad, friend, art professor, and master printmaker, Marwin is also an intense ornithologist.

If we take a closer look, if we take the time to see birds through his eyes, I hope we’re all encouraged to settle down, to pay more attention to the birds, to be more observant of the world in chaos around us, to become louder advocates for our feathered kin.

– Miranda Belarde-Lewis (Zuni/Tlingit)

Miranda Belarde-Lewis (Zuni/Tlingit) is a mother, independent curator and scholar. She has curated exhibitions at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle and the Museum of Glass in Tacoma. One of her research areas focuses on the resilience, strength and vitality provided by Native arts to Native communities. She is an Assistant Professor of Native North American Indigenous Knowledge at the University of Washington’s Information School.

Feathered Relations

A Closer Look: Woodblock Carvings

Marwin Begaye is especially well-known for his highly-detailed linocut and woodblock carvings. Below, you’ll see three prints next to the woodblock from which they were derived.

As you view them side-by-side, consider what details most draw your eye in each form, and why the artist may have chosen to add color in specific areas of the print.

Continue Exploring

View More of Marwin’s Works

Your exploration of Marwin Beyage’s work doesn’t have to end here. View more of Marwin’s mixed media works, woodblock prints, and paintings on his website at marwinbegaye.com [external link].

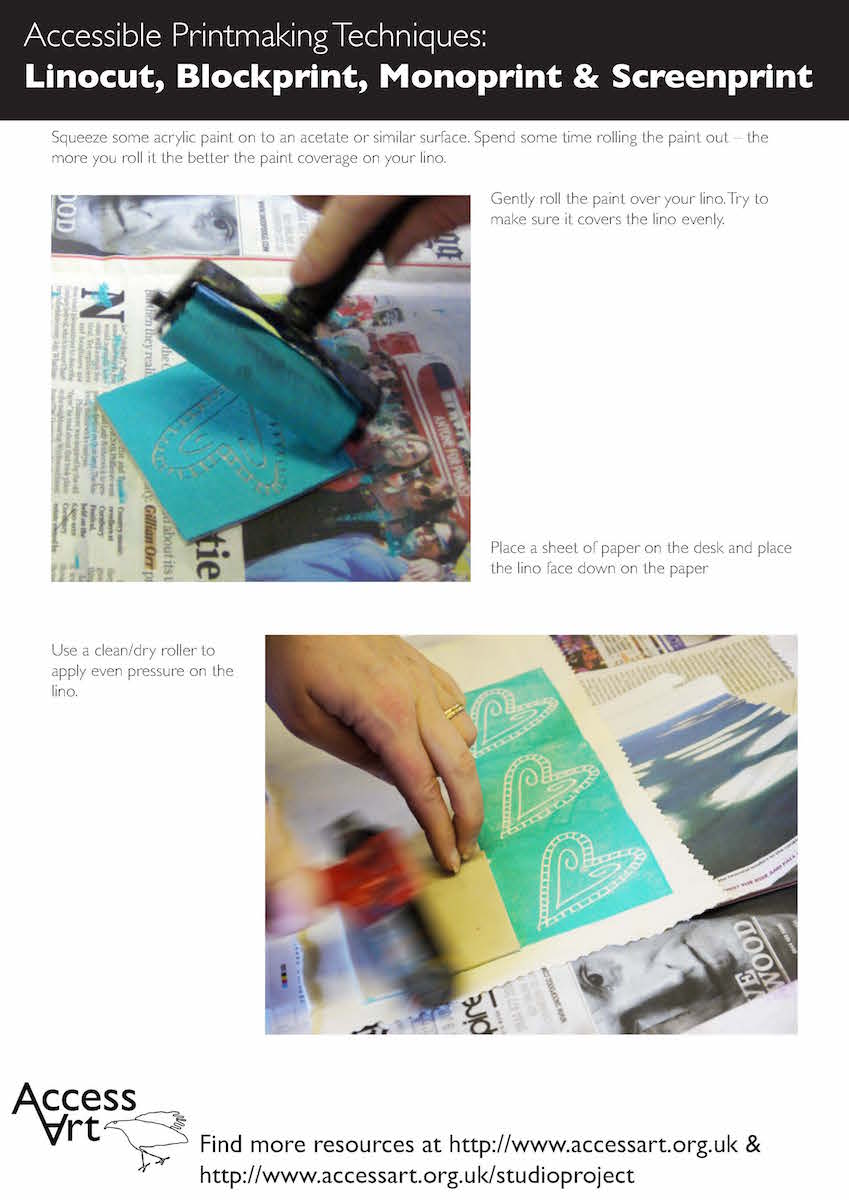

Make Your Own Prints

Create your own prints at home! Learn techniques for making four different kinds of prints — linocut, blockprint, monoprint, and screenprint — with tools that you may have at home, or can purchase from any craft store. Instructions for both children and adults are included.

This PDF is provided courtesy of AccessArt, a UK-based nonprofit supporting visual arts teaching and learning.

Piece It Together

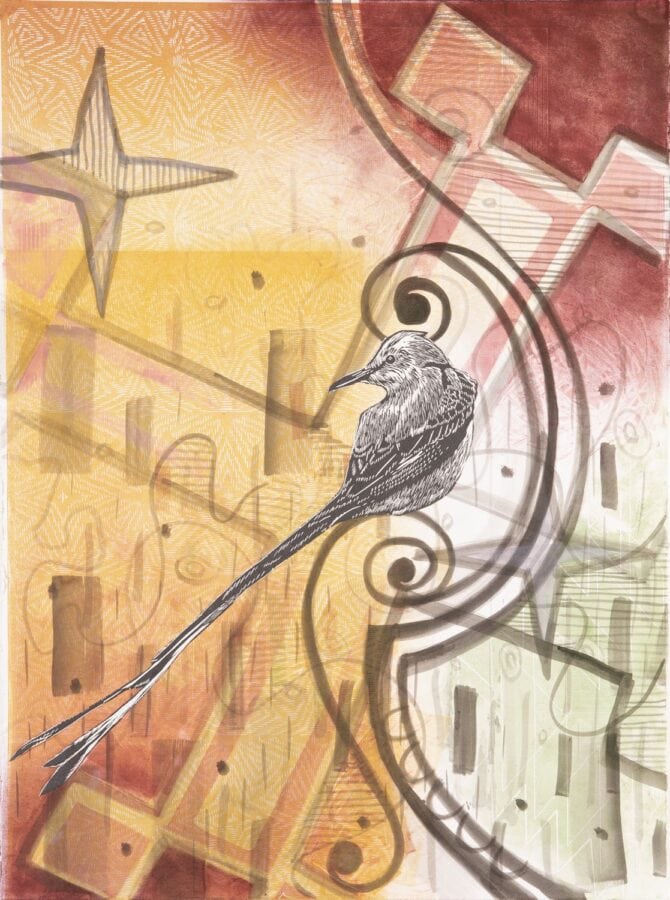

Scissortail 2, 2015, by Marwin Begaye. Mixed-media monotype on paper, 27 x 39 in.

Leave a Comment

We want to hear from you! Share your response to Begaye’s works and the exhibition as a whole below.

Please note: after you post your comment, the webpage will automatically refresh and then return you to this section of the exhibit.

Leave a comment:

Thank You

Thank you for viewing Feathered Relations as hosted by the C.N. Gorman Museum at UC Davis.

To learn more about the museum, visit gormanmuseum.ucdavis.edu.

You can also purchase the catalog for Feathered Relations: Works by Marwin Begaye from the C.N. Gorman Museum.

Feathered Relations originated at the C.N. Gorman Museum at UC Davis and features the works of Marwin Begaye. This online exhibition is brought to you in partnership with Exhibit Envoy. Thank you to Marwin Begaye and Miranda Belarde-Lewis for allowing us to publish their work.

What others are saying:

Breathtaking! So sorry it couldn’t be viewed live and so grateful that it was made available virtually. Thank you!

Beautiful Prints Thank You

Thank you so much for putting these beautiful prints online. I have no opportunity to visit your physical gallery so I would never have known about them otherwise. The detail is stunning and I can see the textile influences. Brilliant!