Presented by the Great Plains Black History Museum

September 6, 2021 – October 18, 2021

“Black and White in Black and White: Images of Dignity, Hope, and Diversity in America” is curated by Douglas Keister and based upon the physical exhibition of the same name touring through Exhibit Envoy.

This exhibition is generously sponsored by Robert A. Terrebonne.

All photos © Douglas Keister Collection except where noted.

Introduction

[Johnson’s photographs] speak to a time and a place where African-Americans were treated as second-class citizens but lived their lives with dignity…You can read about it and hear people talk about it, but to actually see the images is something entirely different.

Michèle Gates Moresi, curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, on John Johnson’s photographs

The beginning of the 20th-century was a time of great promise and hope for race relations in America. This optimistic era was fueled by what was known at the time as the “New Negro Movement,” a period which set the stage for the Harlem Renaissance. No one better captured the essence of this time of advancement than African American photographer John Johnson.

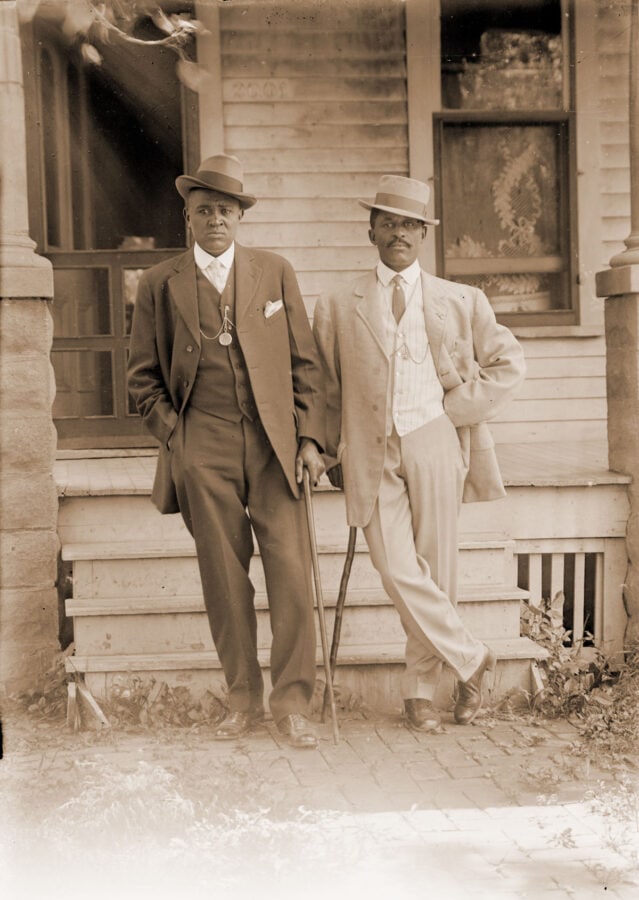

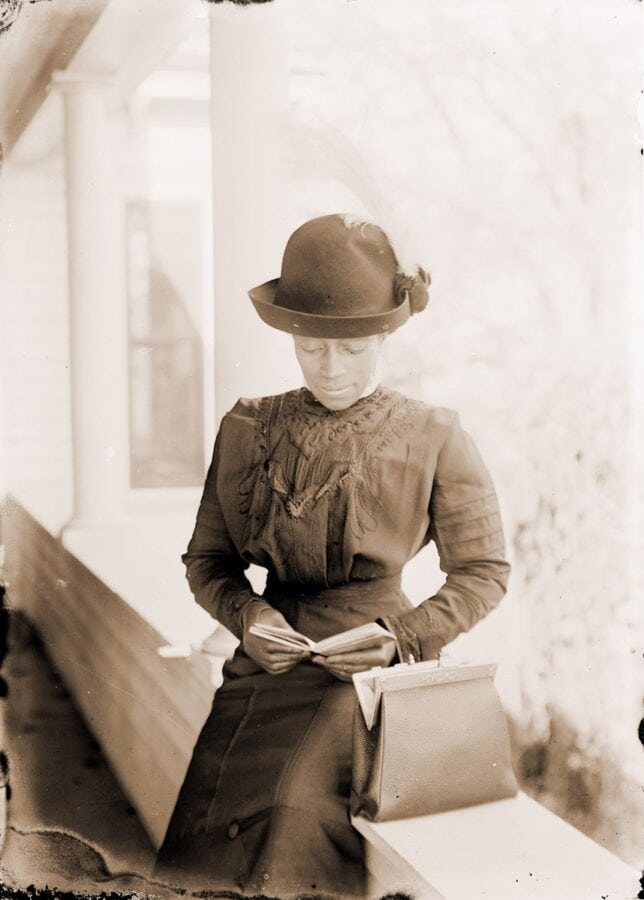

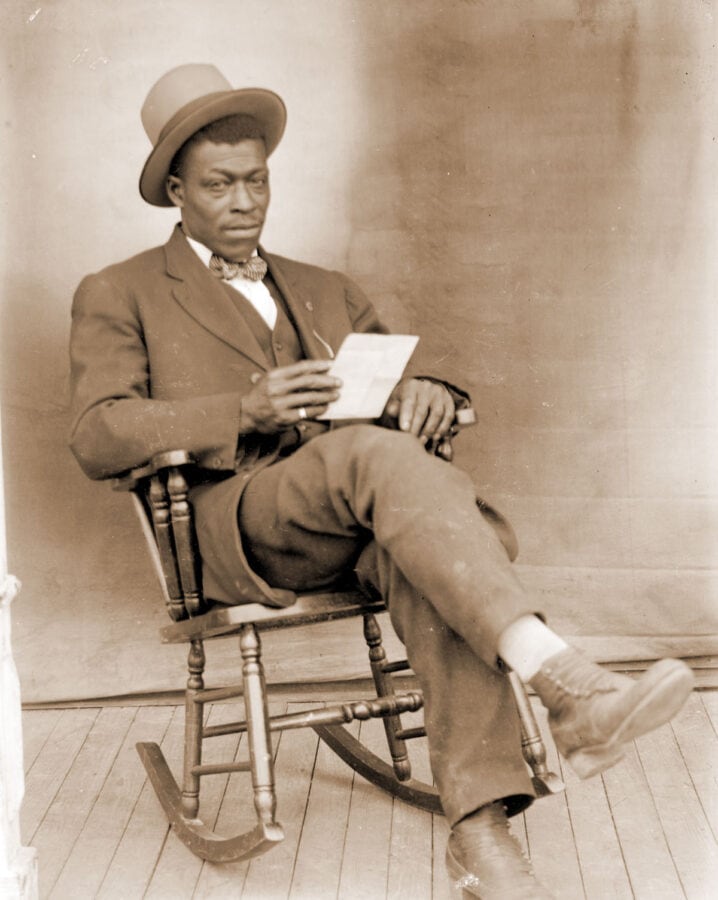

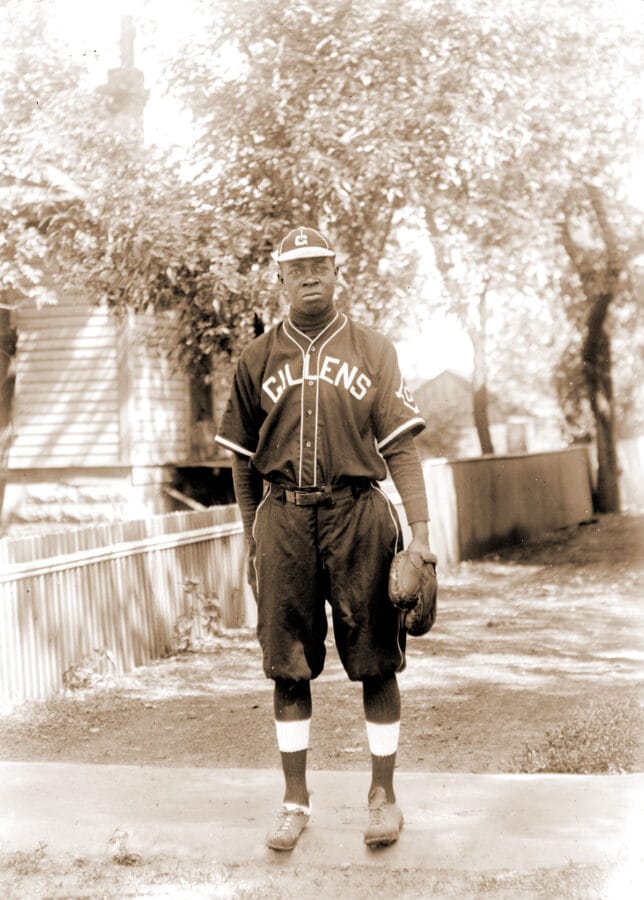

Primarily using his neighborhood in Lincoln, Nebraska as his canvas, Johnson crafted powerful portraits of his Black friends and neighbors from 1910 to 1925. Equally as important as Johnson’s ennobling images of African Americans are his images of mixed racial groups, which depict a vibrant and integrated community. His subjects may have lived modestly, but Johnson’s lens portrayed a nobility and optimism far beyond their circumstances.

These photographs are extraordinary documents of a time of change in America. Indeed, Johnson’s contributions are so significant that the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture acquired Johnson’s work for their collection; Johnson’s work is even on display in their permanent and rotating exhibitions.

A number of the people depicted in Johnson’s photos eventually migrated across the country to pursue better opportunities. They positively impacted their new communities, becoming educators, artists, parents, and business owners.

Navigating the Online Exhibit

As you peruse this exhibit, you’ll be able to dive more deeply into each image, and meet many of the people that John Johnson photographed. To read each caption, simply click or tap on the photograph to learn more. Try it with the images above to learn more about Mamie Griffin and George Butcher, and with the image here to learn more about this musician.

Later in the exhibit, you’ll also see colorized versions of John Johnson’s photographs. These digitally-retouched images can help bring new details into focus, and can help us better imagine the lives of the people that Johnson photographed.

Listen While You Look

Ragtime music, followed closely by jazz and the blues, was all the rage during the years that John Johnson photographed his friends and neighbors in Lincoln, Nebraska. Immerse yourself in the time period with these hit songs, written and performed by Black musicians, as you view the exhibit.

Please note: within this exhibit, you will see some outdated terms in primary source materials.

The New Negro Movement

Why do not more young colored men and women take up photography as a career? The average white photographer does not know how to deal with colored skins and having neither sense of the delicate beauty or tone nor will to learn, he makes a horrible botch of portraying them.

W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Crisis” Magazine, 1923

Setting the Stage for a Movement

Ask many people about pivotal moments in African American history and they will point to the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. The century between those events, however, also saw progress. This was largely as a result of what was then called the New Negro Movement (founded in 1916) and the Harlem Renaissance (1917-1928).

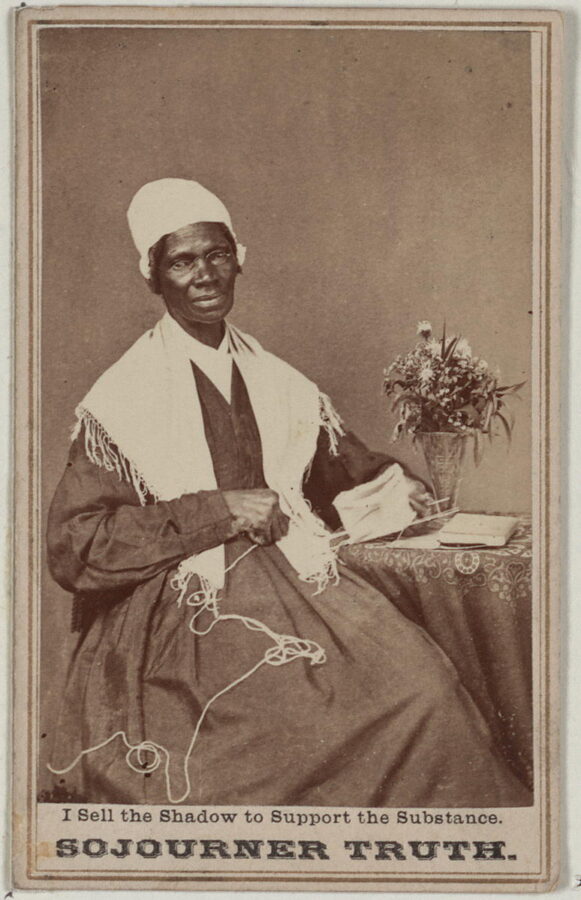

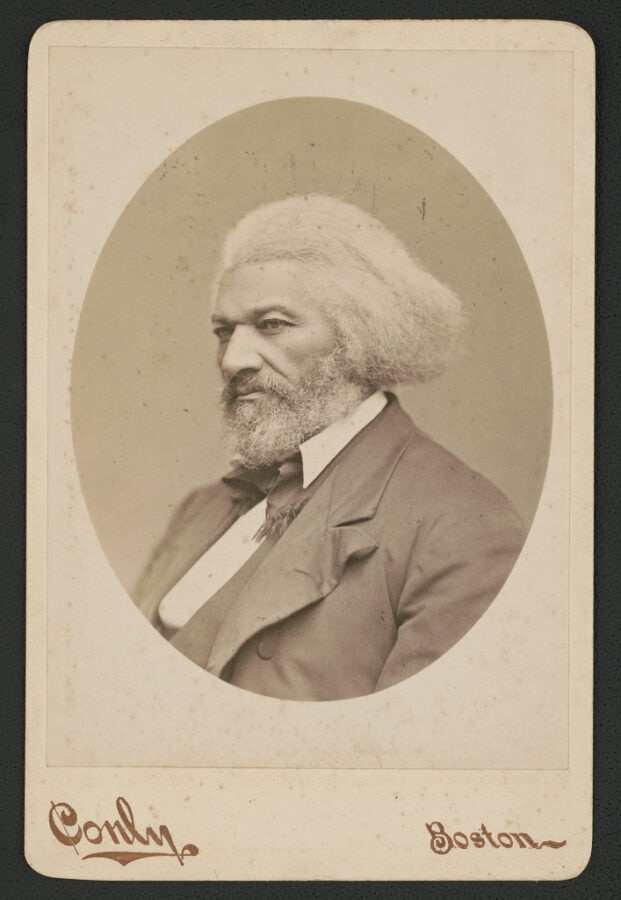

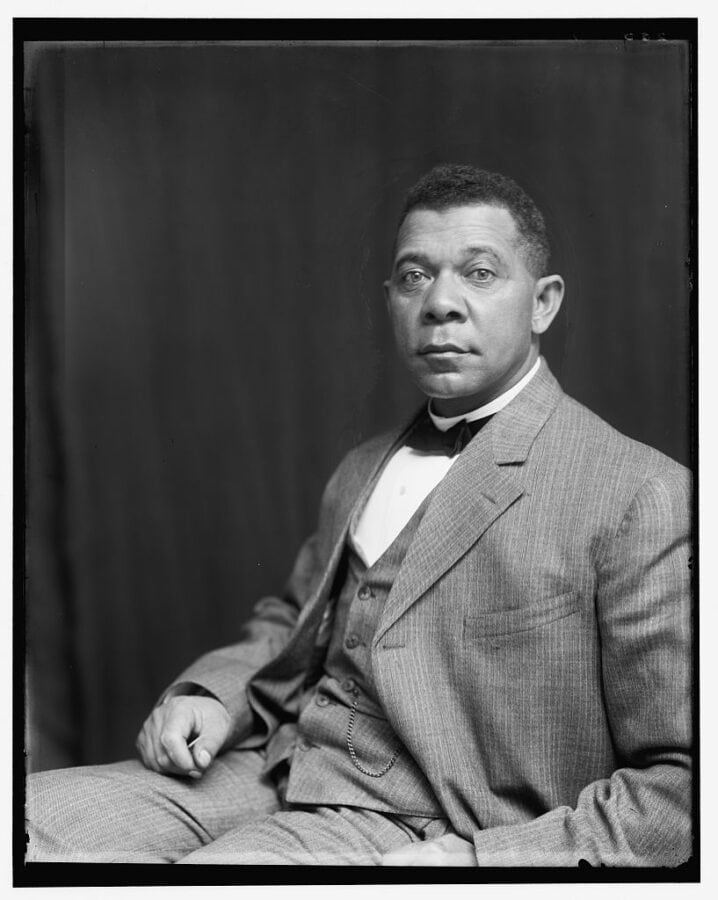

The New Negro Movement, in particular, built upon the work of three key Black leaders who lifted up and called attention to African Americans: Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Booker T. Washington.

Douglass, Truth, and Washington labored for years to show that Blacks were equal with whites, but their work was far from over. They passed the torch to the next generation of African American leaders, who continued to work to defeat segregation and racism. This new period of struggle took place at the same time that John Johnson photographed his family and neighbors, and was deemed “the New Negro Movement.”

The New Negro Movement

The Younger Generation comes, bringing its gifts. They are the first fruits of the Negro Renaissance. Youth speaks, and the voice of the New Negro is heard.

Alain Locke

At the beginning of the 20th-century, Black authors and activists worked hard to discard the stereotype of the “Old Negro,” the plantation slave depicted as subservient, uneducated, and lazy. Instead, they championed what they deemed the “New Negro,” the contemporary African American man or woman who was educated, refined, and sophisticated. Members of the New Negro Movement prided themselves on their political advocacy, and drew attention to inequality and the need for Black empowerment, self-confidence, and organized protest.

Two books, in particular, influenced the movement and advocated for Black education and opportunity: W.E.B. DuBois’ The Souls of Black Folk (1903) and Alain Locke’s anthology The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925). Another well-known manifestation of the New Negro Movement lives on today: the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909 in New York City.

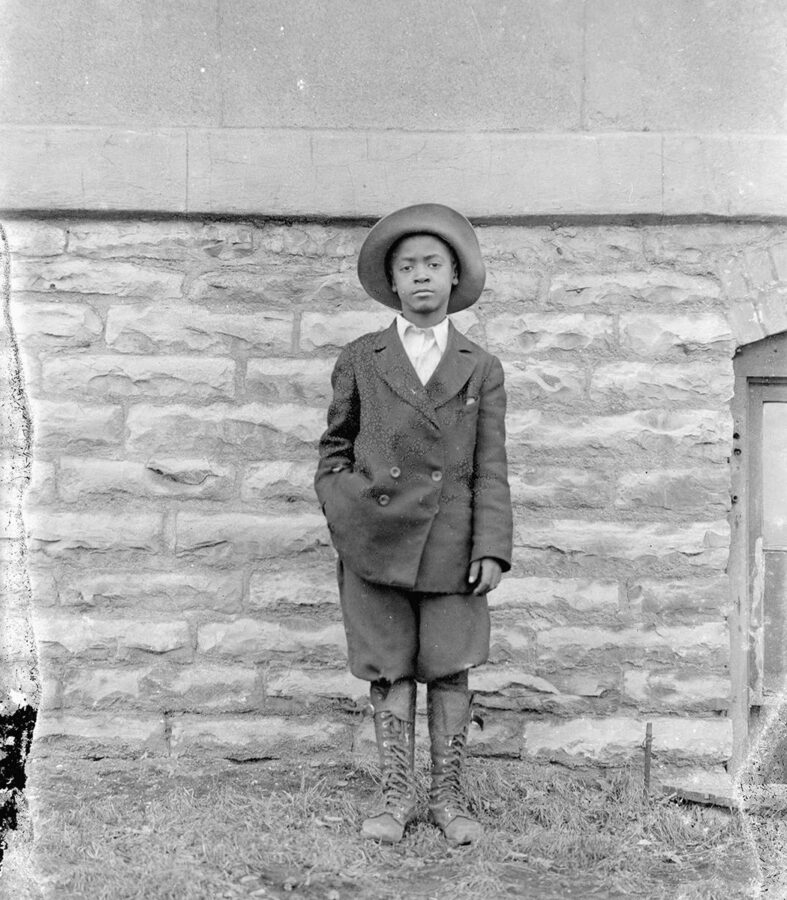

Photographer John Johnson captured the lives of his friends and neighbors in Lincoln, Nebraska in the midst of this movement. As such, it is no surprise that Johnson’s portraits reflect the period’s ideals. His images are studies in empowerment, ennoblement, respect, and dignity. The faces of his subjects radiate hope and strength. And, many of his subjects are photographed holding books, symbolizing the education and intelligence of the “New Negro.”

Uncovering History

Five Decades of Discoveries

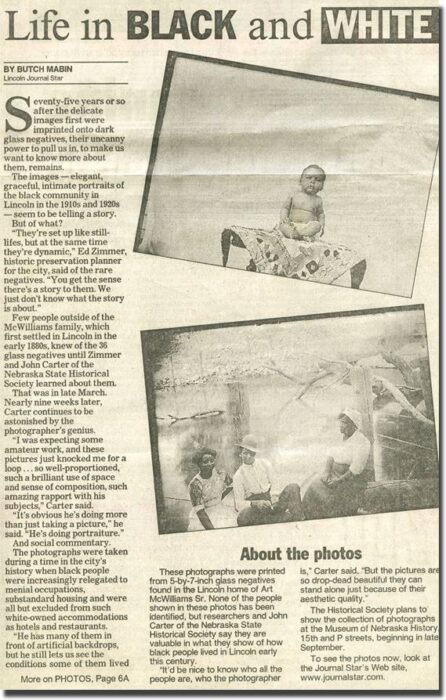

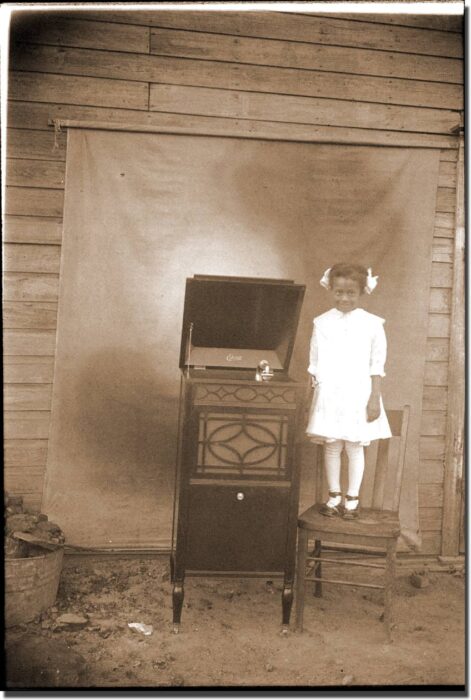

In 1965, as a junior at Lincoln Southeast High School in Lincoln, Nebraska, Doug Keister acquired 280 glass plate negatives. The plates, originally purchased at a garage sale by his friend Doug Boilesen, first struck Boilesen’s fancy because one was thought to show a young girl posing beside a phonograph. After unearthing the plate and adding it to his phonograph memorabilia collection, he sold the others to Keister. Keister immediately made “contact prints” (prints the same size as the negative) from some of the 5” x 7” plates. These prints revealed local street scenes and a number of portraits, primarily of African American men, women, and children.

When Keister moved to California in 1968 to become a professional photographer, Keister stacked the negatives in shoeboxes and stored them in his parents’ basement. A few years later, he transported the boxes to his new home in Oakland.

Over 30 years later, in March 1999, Victor and Juanita McWilliams shared 36 glass negatives with the Nebraska State Historical Society. The negatives depicted the city’s African American residents and were attributed to Earl McWilliams (1892-1960), Victor’s uncle and a one-time assistant at Lincoln’s Townsend Photography Studio. When the Lincoln Journal Star ran a story about the discovery, Keister’s mother saw the article. She sent it to him with a simple note. It read, “Don’t you have some old glass negatives?”

Experts soon concluded that Keister’s collection appeared to have been taken by the same “eye.” A few months later, they entered the national stage through a Newsweek magazine feature.

Keister and Ed Zimmer, Historic Preservation Planner for the City of Lincoln, continued to look into the photographs’ provenance. They studied images for details that would indicate dates, photographic techniques, or personal history of the artist. A major breakthrough came from Ruth Talbert, a woman who remembered an African American man named John Johnson (1879-1953) as the one who took the photographs.

More research revealed a booklet compiled by Johnson: “Negro History of Lincoln, 1888-1938.” The text listed Johnson as the only photographer, with McWilliams and others as assistants. Historians now consider Johnson to be the photographer, but research continues to verify a collaboration between Johnson and McWilliams.

Finding the Photographer

This image is pivotal in our understanding of these photographs. The glass negative reached California as part of the Keister collection, but an original print survived in the possession of Ruth Talbert. She told researchers in 2002, “Mr. Johnny Johnson took our picture,” providing key information related to the identity of the photographer.

Here, Reverend Albert W. Talbert, his wife Mildred, son Dakota, and daughter Ruth (the same Ruth that remembered Johnson as the photographer) posed in front of Newman Methodist Episcopal Church around 1914. The Talberts came to Lincoln in 1914 from Guthrie, Oklahoma, and Rev. Talbert ministered to his African American congregation until 1920. Mother Millie later worked as a hairdresser to support Ruth as she earned her teaching certification at the University of Nebraska.

In this photograph, which was taken around 1917, Dakota is wearing a swastika pin. Long before the Nazi party claimed the symbol to represent its extreme white nationalism and racism, the swastika symbol represented good luck. The symbol is historically seen in different countries, cultures, and religions throughout the world. While it’s unclear why Dakota chose to wear this pin in the photograph, we do know that he was not proclaiming his support of the Nazi party.

The Man Behind the Camera

Who was John Johnson?

In 1879, photographer John Johnson was born in Lincoln, Nebraska in the house his father built. After graduating from Lincoln High School in 1899, Johnson attended the University of Nebraska. But, even for an educated African American man, employment in Lincoln was restricted largely to service occupations or heavy labor. Johnson was no exception. City directories listed Johnson as a drayman (cart or wagon driver), laborer, and janitor at the Post Office/Courthouse.

However, from approximately 1910 until at least 1926, Johnson also worked as an accomplished photographer. He created hundreds of unique images in Lincoln, Omaha, and Kansas City. Working without a studio, most of his extraordinary images were taken outdoors or in homes, churches, and workplaces. That photography was more than a hobby to Johnson is suggested both by the quality of his photographs and by the quantity of his images discovered so far — approximately 500 glass plate negatives have been found in various collections.

Johnson married Odessa Price in August 1918, when Odessa was 27 and John was 39. The couple had no children, and died within months of each other in 1953. They lived in Lincoln for their entire married life.

John’s parents, Margaret and Harrison Johnson, had both hailed from the South. During the Civil War, Harrison Johnson escaped from slavery in Arkansas at the young age of 13 or 14. He “sought protection inside the lines of the First Nebraska regiment,” allowing him to enlist as a private in the otherwise all-white unit. His wife, Margaret, had been born in Mississippi in 1854, most likely into slavery.

When Harrison and Margaret settled in Lincoln, Nebraska, “Hary” worked as a cook at a hotel. After he died in 1900, Margaret remained in Lincoln where she lived with her son. A small, prim woman, Margaret was often seen riding to church “ramrod-straight” in John’s horse-drawn wagon.

Johnson’s Earliest Photographs

The photographs below are the earliest known photographs taken by John Johnson. It’s possible to date these photographs because newspaper articles and other records note the date of each disaster. While we do know the date range of Johnson’s portraits (1910-1925), many of the photos in this exhibit are undated simply because there are no sources to definitively corroborate dates.

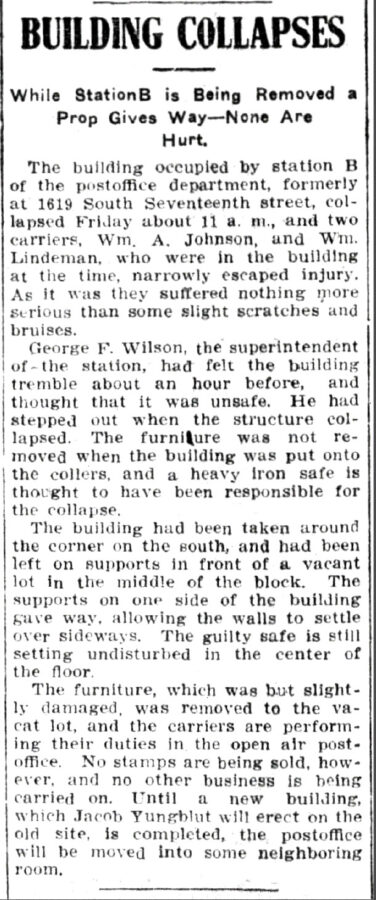

On May 13, 1910, in the process of moving the old post office to another location, the frame building collapsed.

This article reveals that “a heavy iron safe is thought to have been responsible for the collapse.”

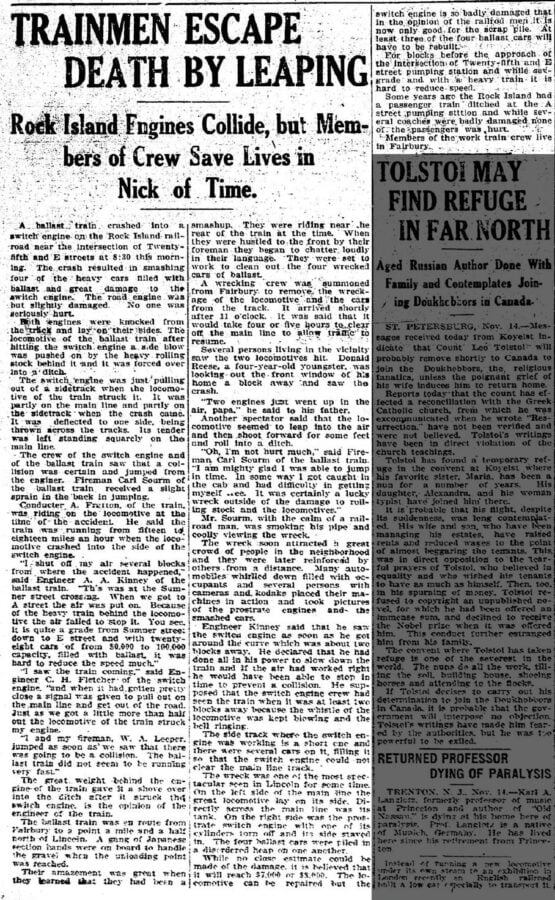

On November 14, 1910, a ballast train collided with a switch engine not far from John Johnson’s home.

An article details the wreck, noting that the two trains that collided were staffed by their crews and a group of Japanese workers.

Scroll over to see all of the images. Click for full captions.

Life in Lincoln

John Johnson’s photographs deftly captured the lives of his family, friends, and neighbors in Lincoln, Nebraska. Click on each photograph to learn more about the men, women, and children in each picture, and to view each photograph as a full-size image.

Hannah Rosier, c. 1910-1915

Recent research reveals that the woman depicted here is Hannah Rosier, who lived in Lincoln for over 40 years.

Hannah’s father, Daniel Bruce, was born in 1779. He bought his wife, Hannah Brigette, from her slave master when she was 38 yrs old. Their daughter, also named Hannah (and the woman pictured here), was born in 1821. The family was free and lived in Washington, DC.

In 1848, Hannah married young John Rosier, who was a barber. Sometime in the late 1850s, Hannah and her family moved to a small farm in Wisconsin. By the early 1860s, John was drafted into the U.S. Army. He fought with the 5th Wisconsin Infantry Reorganized Co E, and was sent to Virginia to pursue General Lee and cause him to surrender; John looked on as Lee did so at Appomattox. John returned home to his farm after the war but passed in 1869, possibly from war injuries. Hannah and her children soon left the farm and sought out a new life in Lincoln, NE around 1872. In Lincoln, Hannah spent over 40 years nursing women and delivering their children. She died in 1915 at the age of 94, close to when this photo was taken.

Thanks to Stan Schmunk for his additional research.

Scroll over to see all of the images. Click for full captions.

The Colley and Malone Families

Walter R. Colley (1871-1970) is pictured at right with his son-in-law Clyde Malone (1890-1951) standing behind him. Colley’s wife Lula (1875-1958) shares the bench with her husband. Between them is their daughter Izetta (1892-1966); at left, her sister Helen.

Clyde was 20 and Izetta only 18 when they married in 1910, around the time this photograph was taken. Clyde wrote in 1946: “After graduation from high school, I was fatally bitten by the matrimonial bug and deluded Miss Izetta Colley, of the Missouri Colleys, into saying ‘I do’, (and she has for lo’ these many years).” Their marriage lasted over 40 years.

Clyde was later the executive director of the Lincoln Urban League. Following his death in 1951, the Lincoln Urban League was renamed the Clyde Malone Community Center.

Then and Now

Over the past century, some of the locations that Johnson photographed have changed drastically or disappeared. Others, however, remain recognizable. These two short videos, both with no sound, show how we are still connected to the people and places of 100 years ago.

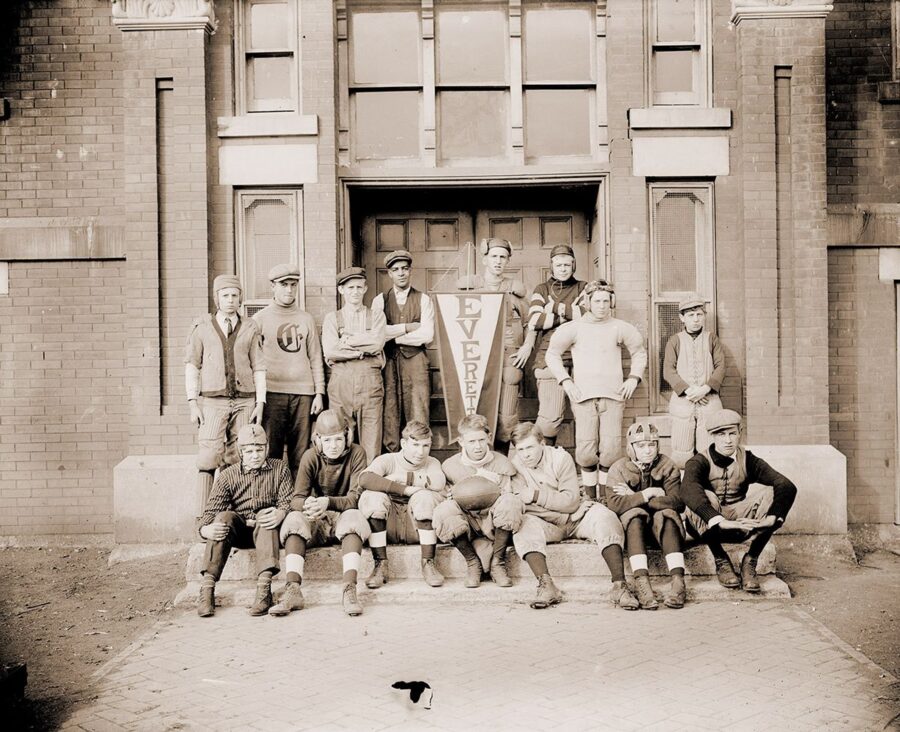

Together in Black and White

One reason that John Johnson’s work is so important is that his images depict people of different races living, working, and playing together. These images of mixed racial groups reveal a vibrant and integrated community in America’s heartland.

The Zakem Children and Friend, c. 1921

After this photograph was featured in Newsweek magazine in November 1999, collection owner Douglas Keister received a call from a radiologist in Atlanta. The man, who identified himself as Jim Zakem, said the child on the far left was his father, also named James. Jim provided detailed information on the family.

Lebanese-born Alexander K. Zakem (1879-1942) immigrated to America in the 1890s and came to Nebraska around 1900. When his first wife died, he returned to Lebanon, married a woman named Anise, and came back to Nebraska, joining relatives who had settled in the area. He operated restaurants in Lincoln and smaller Nebraska communities.

Alexander and Anise had three children. James, born in Michigan in 1917, is pictured at left beside little sister Lillian. Older sister Adeline, at right, was born in Montreal in 1916. The blonde boy was a playmate.

The Zakem children and their friend, above, appeared in another of John Johnson’s photographs taken on the same day and in the same location. This incredible image shows two Black men, three Lebanese-American children (the Zakems), and a Caucasian boy, who was most likely a Volga (Russian) German. A century ago, this would have been an extraordinary group.

Surprisingly, this photo was enclosed in a heart at the end of a ceremonial wooden axe. This axe may have been used in rituals for the Colored Odd Fellows, a secret society. Like their white counterparts, many African Americans belonged to these clubs, which were usually segregated along the lines of race and gender.

The Odd Fellows had dozens of symbols. One of their primary symbols was the axe, often accompanied with three links of a chain (friendship, love and truth) and a heart in hand (charity). The axe symbolized that Odd Fellows must cut down and remove barriers to friendship, love, and truth in their lives.

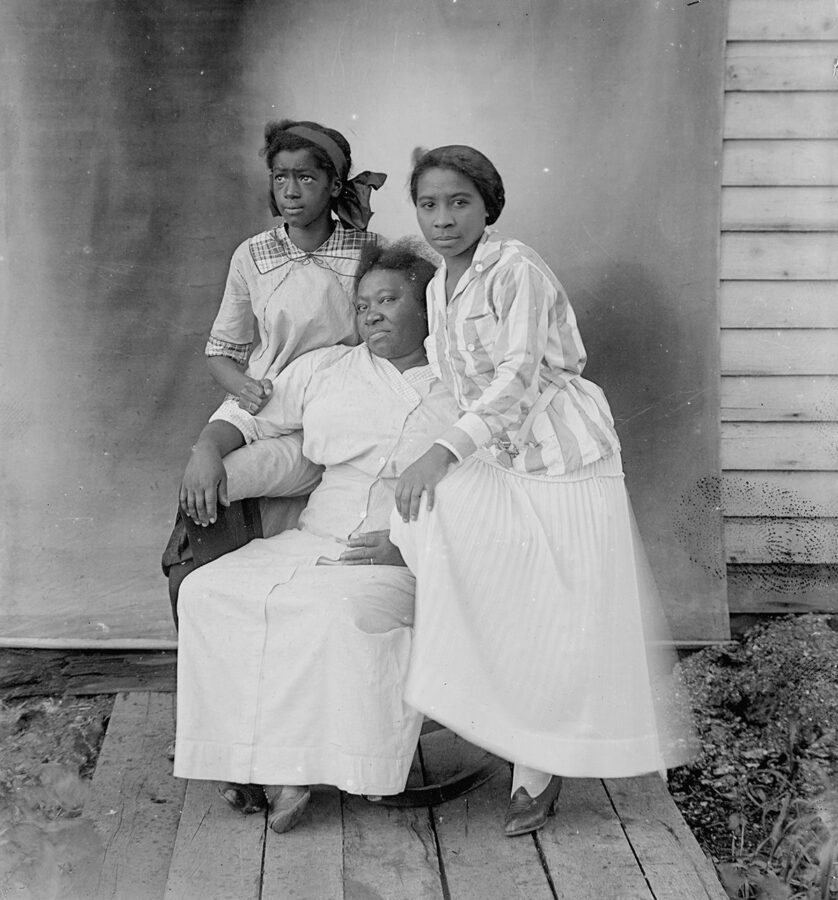

The Thomas Family and Frances Hill

Although family members, friends, researchers, and Lincoln residents have helped uncover the stories behind some of Johnson’s photographs, details remain relatively sparse for many. The Thomas Family and Frances Hill are two clear exceptions. These two stories reflect how family lore and historic documents help shed more light on our shared past.

The Thomas Family

Cora and Alonzo “Lon” Thomas operated a small grocery from the front room of this house at 715 C Street, which was originally built for a Civil War veteran in 1886-1887. Four of their five children are seen here. Baby Lonnie sits on Herschel’s lap, Agnes stands at left, and son Wendell stands at the center. The young man at right is probably Lucius Knight, their mother’s half brother.

The Thomas family and many other African American families lived in the South Bottoms, a neighborhood they shared with many Germans from Russia, Lincoln’s largest immigrant group. The little blonde girl who leans into the right edge of this view was Marie Busche, seen here at age 3. The daughter of a German immigrant, her presence in this picture reminds us that Lincoln’s residential neighborhoods were not segregated by race in the early 20th century; working-class people of many ethnicities lived together. A few years later, however, residential segregation became prevalent in Lincoln. A close-knit black neighborhood arose from that adversity.

As the years went on, the Thomas family illustrated the change that slowly came to America’s heartland. Older brother Wendell worked the jobs typically available to African Americans in Nebraska – waiter, clerk, porter, laborer, and janitor – before founding the Thomas Funeral Home in Omaha. Baby Lonnie eventually became a championship golfer, worked in the county assessor’s office in Omaha, and was treasurer of a number of civic organizations. His wife, Delores Hall, became a teacher, civil rights activist, and director of the Urban League in Sacramento, California. The couple raised four children; daughter Deborah Thomas became a singer/songwriter/performer who has recorded with entertainers like Whitney Houston and Janet Jackson, performed with Dionne Warwick and Gladys Knight, and recorded and toured with Lionel Richie and many others. Below, she reflects on her father’s experiences living in Lincoln in the 1920s.

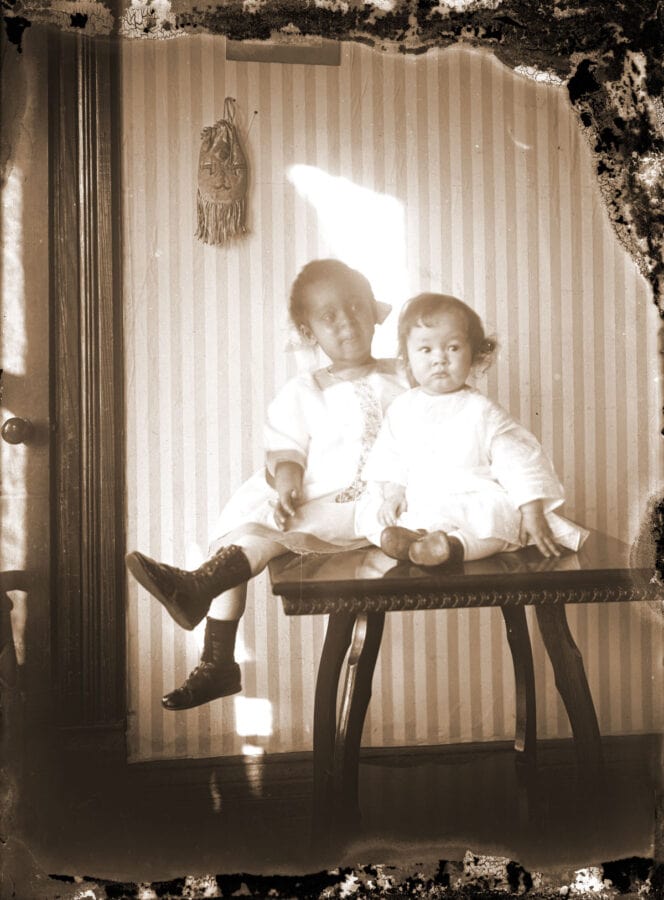

Frances Hill

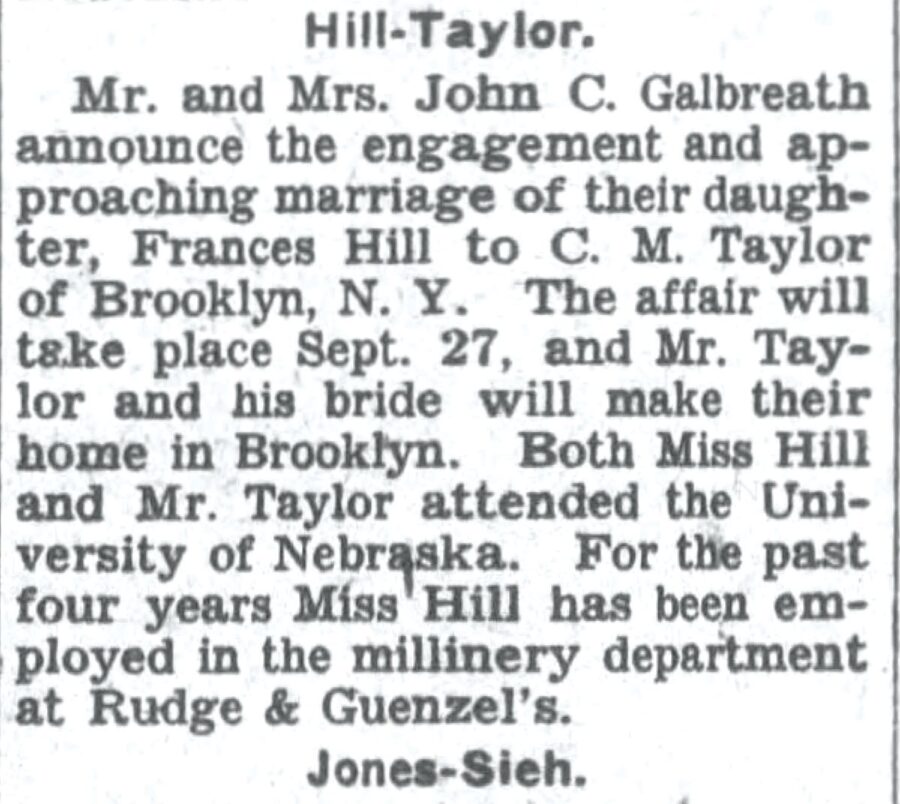

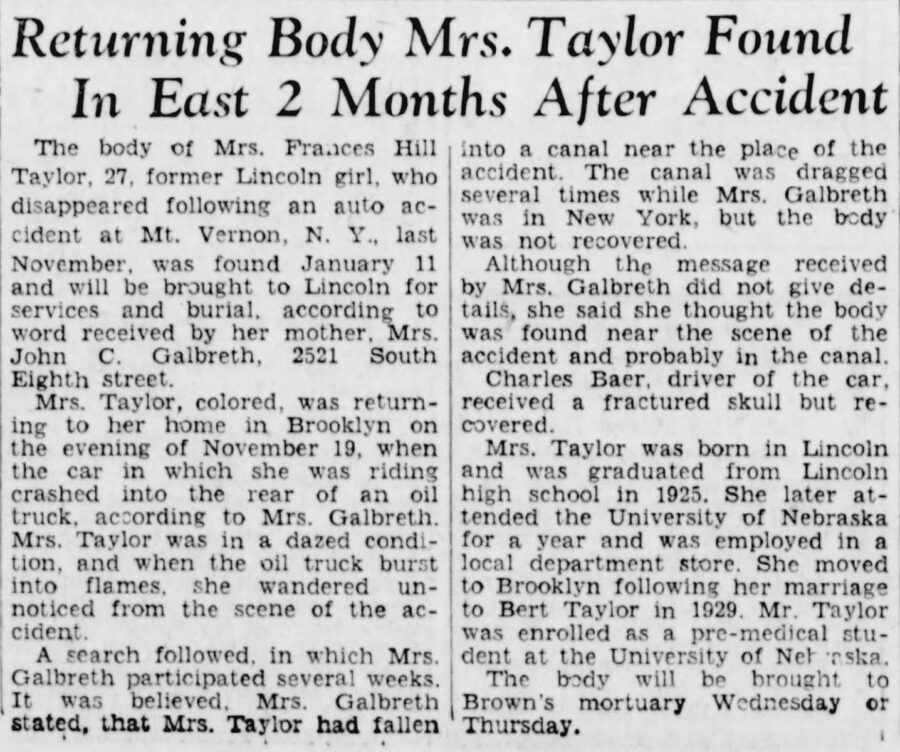

Once a person’s name is verified, old newspaper clippings can help to illuminate their story. Such was the case of young Frances Hill, whose marriage and tragic death were documented in Lincoln, Nebraska newspapers.

Frances Hill was born in 1904. We first meet Frances through these interior photographs, with bold wallpaper providing a backdrop. It’s likely that this was Hill’s home at 524 N. 9th Street. There, she lived with her mother, Mabel Galbreath, and her stepfather, John C. Galbreath. John was sometimes a waiter; in the 1920 census, he was listed as operating a restaurant. The 1920 census reflects that 15-year-old Frances lived in the Lincoln home.

The 1920 census also lists Ben and Lottie Corneal, who lived next door to the Galbreaths at 520 N. 9th Street. Lottie and Ben had two boarders at that time: Aaron Douglas, a 21-year-old university student, and a barber. Aaron Douglas went on to become one of the most accomplished and influential visual artists of the Harlem Renaissance, joining W.E.B. Du Bois as an art critic at his important magazine, The Crisis, and earning the nickname “the father of Black American art.” Douglas lived in Lincoln for about 7 years; it is likely that next-door neighbors Aaron and Frances were friends.

After Frances graduated from high school, she worked at a local department store, selling women’s hats in the millinery department. She also attended the University of Nebraska, where she met Bert Taylor. Frances and Bert fell in love, and they got married in September of 1929. Together, they moved to New York City, where Aaron Douglas also lived. Whether Aaron and Frances communicated at this time is unknown, but it’s likely that they kept in touch.

Tragedy occurred in November of 1932. As a newspaper article tells us, Frances was riding in a car that crashed into an oil truck. After the accident, “[she] was in a dazed condition, and when the oil truck burst into flames, she wandered unnoticed from the scene of the accident.” Frances went missing for several weeks, and her mother helped organize a search for her. Sadly, Frances’ body was found almost two months after the accident, and her body was returned to Lincoln for the funeral and burial. Frances was 27 years old.

Photography Then and Now

Glass Plate Negatives

In the early 20th-century, most photographers captured images using black and white negatives. Amateurs often took photographs on flexible film, usually made of nitrocellulose or cellulose acetate. Embedded on the film surface was a sensitized coating, called an emulsion, that was activated by light.

While amateurs took pictures using film, more professional photographers like John Johnson often took photographs on glass plates embedded with emulsion. Although glass plates are more stable and last longer than film, they are also very breakable. And, unlike its film counterpart, which allowed for many pictures to be taken on one roll, only one picture can be exposed on a glass plate. This made glass plates much more expensive than film.

Whether using flexible film or glass plates, the photographer next took the exposed image into a darkroom. There, she or he used chemicals to process the film or glass plate, turning it into a negative. On these negatives, black is white and white is black (see first picture).

If the photographer liked how the negative looked, she returned to the darkroom and placed the negative on top of a sheet of photographic paper. She then shined a light on the negative to expose the photographic paper. Using other chemicals turned the photographic paper into a black and white print (see second picture).

Professional photographers often took the process one step further by applying a sepia brown tone (see third picture). This application was particularly popular for portraits.

Bringing Photographs to Life through Color

Before the widespread availability of color film in the 1950s and 1960s, most photographs were taken in black and white. For special occasions such as weddings and formal portraits, photographers often hand-colored photographs using time-consuming and tedious air brushing and tinting techniques.

Nowadays, digital photographic artists can use a variety of techniques to apply color to old photographs. Members of the “Teach Me to Color” Facebook group colorized the images seen here. Although the artists may not know the precise colors of the clothing or objects in Johnson’s photographs, the group refers to vintage clothing, fabric swatches, and other historical research to inform their work.

These reimagined interpretations of John Johnson’s photographs give the subjects new life, highlighting details and nuances that were not always readily noticeable in the original versions.

Scroll over to see all of the images. Click for full captions.

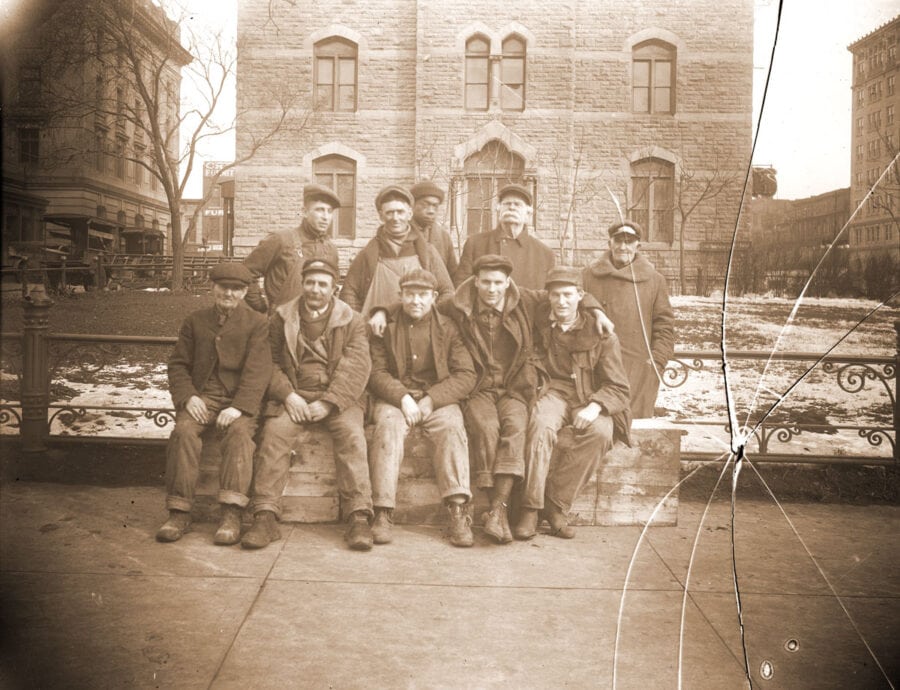

Repairing Damages Electronically

Additionally, electronic graphics programs can be used to repair damaged photographs and reassemble broken glass negatives. Glass negatives are understandably prone to breakage. The most severely shattered are lost, but ones with less severe breakage can be pieced together on a scanner bed. These “before” and “after” images of Johnson and his fellow workers exemplify the mix of physical and digital reconstructions that can be applied to a broken negative.

Explore More

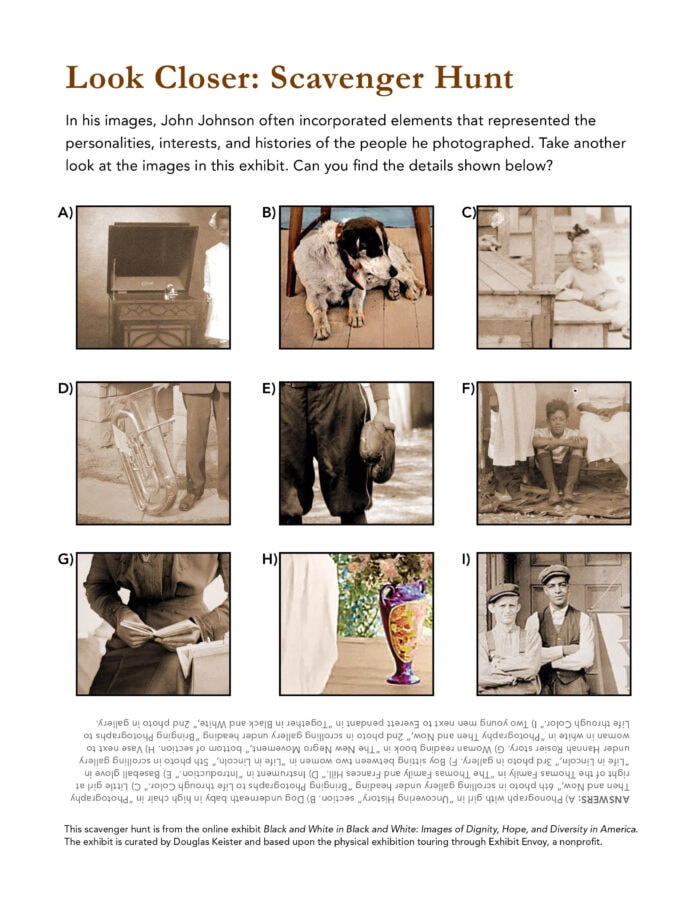

Look Closer: Scavenger Hunt

John Johnson’s photographs are rich with details, and give us more insights into the lives and interests of the people he photographed. Take a look back through the exhibit in this scavenger hunt. Can you find these details within the photographs on display here? What can these details tell us about the men, women, and children in each photograph?

Note: all details are drawn from still photographs in this exhibit. No details come from the videos in the exhibit.

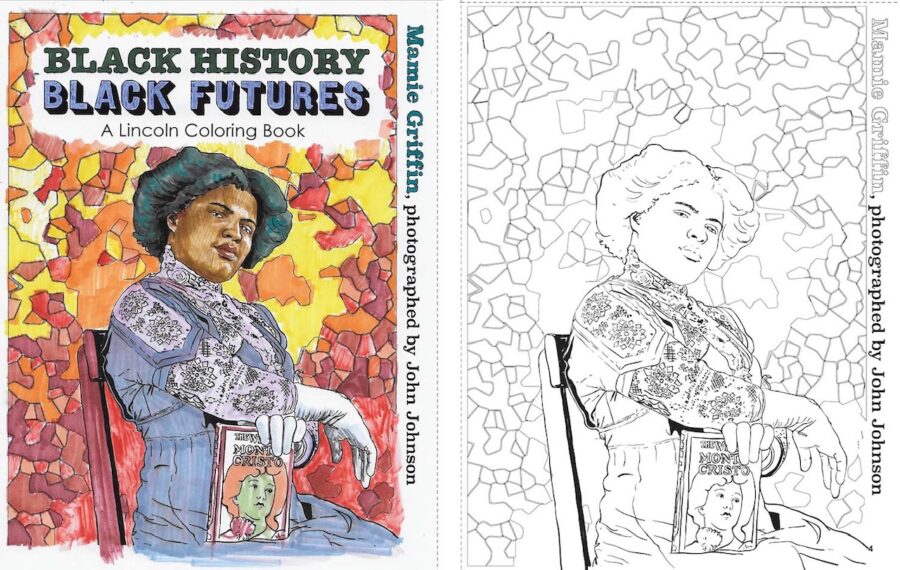

Color It In: Mamie Griffin, 1914

Mamie Griffin worked as a cook in Lincoln, Nebraska. In 1914, she posed for a photograph with the romance novel, “The Wife of Monte Cristo,” for her portrait. On close inspection, Mamie’s hairstyle matches the one of the woman on the cover. It is quite possible that Griffin’s dress, pose and hairstyle is visually intended to say, “I’m just as good as the woman on the book cover.” That ethos was a basic tenant of the New Negro Movement.

Drawing by Katharen Wiese, 2021, for the Black History Black Futures Coloring Book, photo reference by John Johnson of Mamie Griffin, 1914, courtesy of Douglas Keister. Download a free coloring book or learn more at bit.ly/BLKArtKit [external link].

Piece It Together: Dorothy Loving with Plants on the Porch

This puzzle features a colorized photograph of, likely, Dorothy Loving, who graduated from Lincoln High School and was an active member of Quinn Chapel. To view the full photo as you work, click on the square white icon with two small mountains.

Photograph of (likely) Dorothy Loving by John Johnson. Colorization by Lori Zaza.

Watch the Exhibit Tour: Short Documentary “Forgotten World” from PBS

Before becoming an online exhibition, “Black and White in Black and White” traveled across the United States as a physical museum exhibition. NET Nebraska, Nebraska’s PBS & NPR Stations, created a short documentary about the exhibition while it was installed at the Nebraska History Museum in Lincoln, Nebraska. See more of Johnson’s work, catch glimpses of the in-person exhibition, and learn more about these photos’ significance in this 7-minute video.

Leave a Comment

What item represents you?

Many of the people that John Johnson photographed chose to hold items like books and newspapers, musical instruments, baseball gloves, or medicine bags. If John Johnson were to photograph you today, what item would you pose with? How does this item reflect what’s important to you?

You may also share any general comments on the exhibit here. We look forward to hearing from you!

Please note: after you post your comment, the webpage will automatically refresh and then return you to this section of the exhibit.

What item would you include in your portrait, and why?

Thank You

Thank you for viewing Black and White in Black and White, hosted by the Great Plains Black History Museum and sponsored by Robert A. Terrebonne.

The Great Plains Black History Museum’s mission is:

- To preserve, educate, and exhibit the contributions and achievements of African Americans with an emphasis on the Great Plains region.

- To provide a space to learn, explore, reflect, and remind us of our history.

The Great Plains Black History Museum would like to thank Exhibit Envoy for the opportunity to feature the Black and White exhibit.

The Great Plains Black History Museum is currently open by appointment on Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays from 1:00-5:00. To schedule an appointment, visit the museum’s website.

Do you recognize any of the people in these images? Contact the curator, Doug Keister, at [email protected] with any and all information you may have to share. This is an ongoing project, and your insights are important!

Black and White in Black and White: Images of Dignity, Hope, and Diversity in America features selected images from the Douglas Keister Collection [external link] and is presented with support from California State University, Chico. The online and physical exhibits are traveled by Exhibit Envoy.

Special thanks to the people and organizations that made this exhibit possible: Axel Boilesen; Doug Boilesen; California State University, Chico; David Cohen; Tray Robinson, Director of the Office of Diversity and Inclusion, CSU, Chico; Joel Zimbelman, Dean of Humanities, CSU, Chico; Ed Zimmer, Historic Preservation Planner, City of Lincoln; and Dr. Paul J. Zingg, President Emeritus, CSU, Chico.

What others are saying:

I follow you on Facebook, and I honestly can’t choose any, particular photo, but I am amazed at how colorizing the photos brings them to life. It is like they are just there in our own period of time.

I teach black history, and I must say the photos also bring alive the history of the period, if one realizes that the Plessy v. Ferguson case was settled in 1896, and it took another 21 years for segregation to be implemented. That is history! I realize that during that 21 year period history was occurring, and people weren’t thrust into this artificial separation of races custom that so enveloped the nation. Your photos also make me ask the greater question of the Zakem children, and how they were treated. They have dark features and straight hair, but aren’t too distinguishable from black people at the time who were more or less mixed race.

If I could pose with one item, it would be my standup base and on the front porch. I love the front porch photo. I really enjoyed the exhibit, I am not from Nebraska and don’t often think about the black people who lived here and what they did.

I honestly cannot pick one item. All I can say is that I will make sure that my family and my ancestry and heritage are represented. I stumbled upon this in this early morning, and it was just what I needed to immerse myself in our past. These common yet uncommon images are essential to educate us about our history and remind us of our legacy. It is even crucial for me to share this with my children to inspire them. The most fulfilling feeling about this exhibition is the sense of family I felt. I was drawn to each picture as if they were my family members. Thank you for adding notes to every image. I enjoyed reading about all of them. May they rest in peace and continue to shine on us and inspire us to continue being about Black Excellence.