Presented by Laguna College of Art + Design

March 9, 2025 – May 4, 2025

Introduction

Today, more women than men have tattoos.

Almost a quarter of American women have permanent ink, compared to just 19% of men. Younger people are even more likely to be tattooed, as more than a third of Americans between the ages of 18 and 40 have skin art.

But, what about the first women to get tattooed? Who were they, and why did they get inked?

They came from across the U.S. and crossed class lines. From the society women who followed trends, to the working-class women who worked in circus sideshows, American women have always had an intimate and fascinating relationship with tattoos – and in California, it was no different.

Step right up to discover stories of just some of the tenacious and tattooed women in California’s history, all of whom lived and worked in the Golden State prior to World War II.

Tattooed and Tenacious: Inked Women in California’s History is a traveling exhibition from Exhibit Envoy in partnership with the Hayward Area Historical Society and History San Jose. The exhibit was curated by Amy Cohen, who is only slightly tattooed and often dreams of writing a book about some of the Tattooed Ladies you’ll meet here. Special thanks go to Lyle Tuttle, Adrienne McGraw, and Susan Spero for their support of this project.

Navigating the Online Exhibit

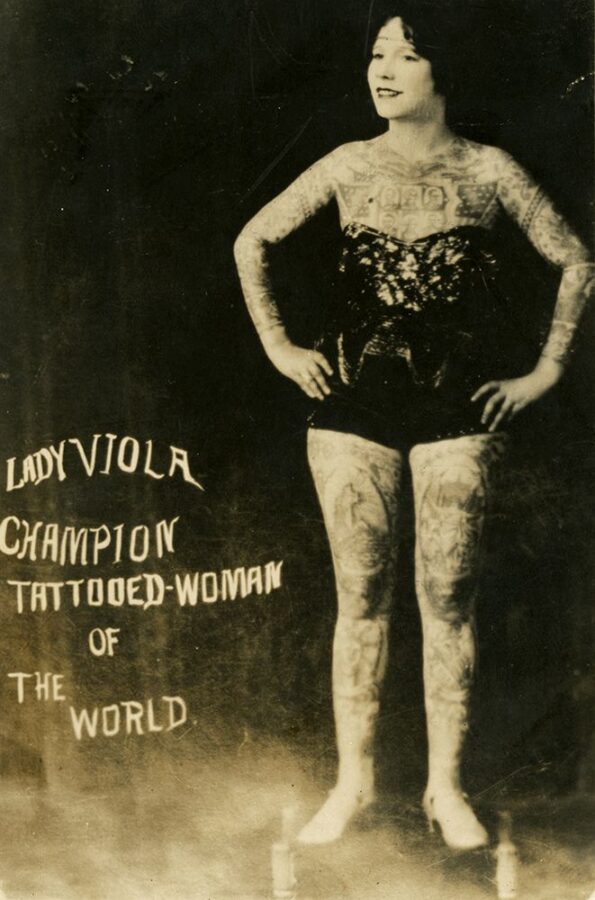

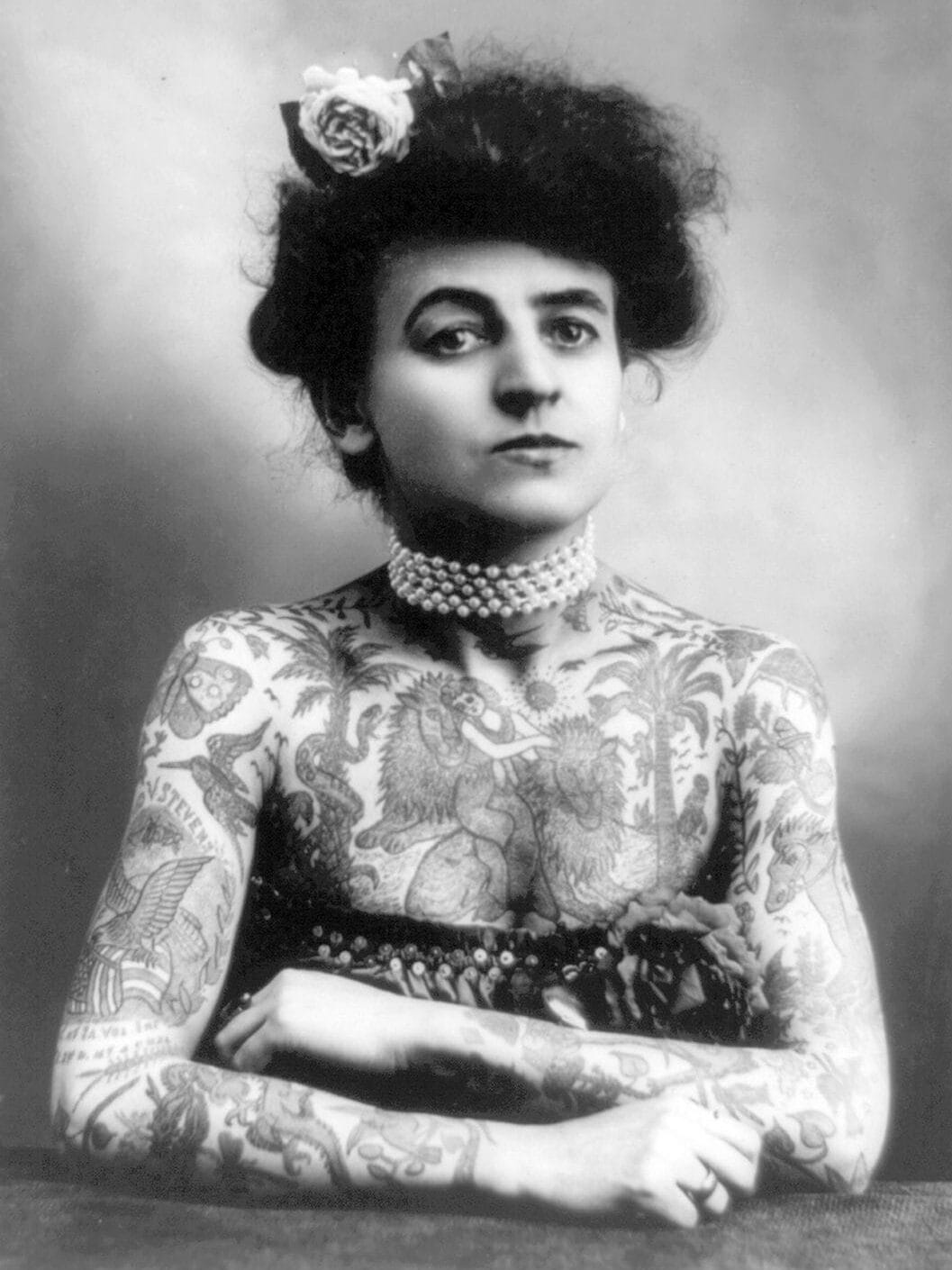

As you peruse this exhibit, you’ll be able to dive more deeply into the images presented. To discover more about the woman or item seen in each image, simply click or tap to learn more. Try it with the image here to learn more about Lady Viola, who was a tattoo artist and performed as a Tattooed Lady.

Please note: this exhibition contains some nudity.

How to Tattoo

Tattoo needles push ink into the skin to leave a lasting mark.

Originally, all tattoos were done by hand. First, the tattooist would dip a single needle, sharpened bone, thorn, or other stylus into pigment. Then, she or he would poke the stylus into the second layer of skin, forcing the ink a millimeter deep. Sometimes called “hand tattooing” or “stick-and-poke,” this method is still used around the world.

In the U.S., most tattooists use an electric tattoo machine. Patented in 1891, the machine punches from one to thirty-two pointed needles through the skin at once. Tattoo ink is then forced into the open holes.

Needles can puncture the skin up to 3,000 times per minute during a tattoo. Artists use a foot pedal to control the machine’s electric motor, which in turn controls the speed that the needles move. Tattoo artists also use different types of needles for different parts of the process, depending on how detailed the image is or how much ink they want delivered to the skin at once.

The ink is typically made of metal salts – like zinc (yellow or white), cobalt (blue), and iron (black, brown, and red) – and suspended in a carrier solution. The carrier, usually ethyl alcohol or purified water, helps to keep the color evenly distributed while also disinfecting the pigment.

Inked people often describe the sensation of getting tattooed as similar to a bee sting, a pinch, or even a slight tickle. If you’ve never been tattooed before, try pinching yourself a few times in a row to get an idea of what it feels like. But remember, the level of discomfort depends on a number of factors, including the location of the tattoo, the skill of the tattoo artist, and personal pain tolerance.

Native Women’s Ink

From north to south, and from the valley to the coast, Native women are part of a rich tattooing tradition.

Whether done to ensure a long and happy life, to enhance a woman’s features, or as part of a complex puberty ritual, almost every California tribe has a tattooing tradition.

While tribes like the Pomo, Eastern Miwok, and Chukchansi practiced body tattooing, California native women most commonly inked their chins. Designs varied by tribe, but usually consisted of straight lines of varying thicknesses, dots, or zig zag-type lines. Often, a female elder held special knowledge of tattooing and any related rituals, making these women the earliest female tattooists in the state.

Chin tattoos became less and less common throughout the twentieth century as the U.S. government attempted to permanently erase Native traditions and cultures. But now, some California Native women have revived the practice, permanently inking their faces using the same hand tattooing process as their ancestors. Bertha Peters and Lyn Risling, pictured below, are just two contemporary Native women who chose to get tattooed with their tribes’ traditional designs.

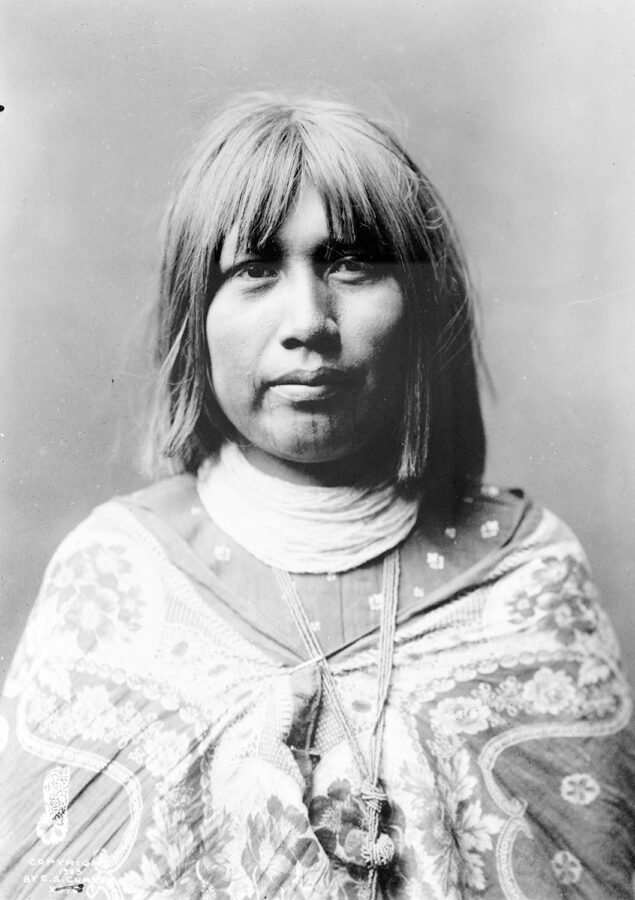

Olive Oatman

Traveling west with her family in 1851, 13-year-old Olive was kidnapped by members of a Yavapai tribe.

Treated as slaves by the Yavapai, Olive and her sister were held captive for a year before they were traded to a friendly Mohave tribe in Southern California.

It was near the border between modern-day California and Arizona that Olive received her facial tattoo. These five blue lines were carefully placed to emphasize Olive’s broad features. Olive’s upper arms were also marked with vertical bands. This ink physically reflected the love of her Mohave family, and was a permanent reminder of this even after she returned to white society in 1856.

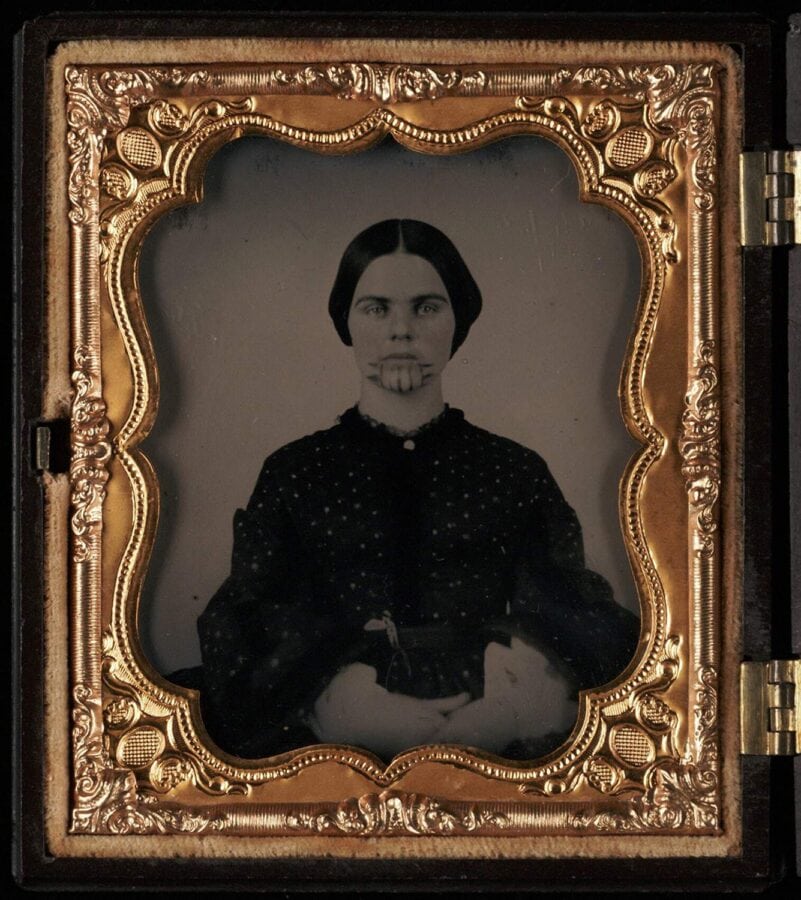

Wealthy Women & Tattoo Fads

In 1897, The New York World reported the shocking “fact” that 75% of American society women had permanent ink.

While it’s highly unlikely that 75% of these women really got tattooed, upper-class American women had indeed jumped on the tattoo bandwagon. Taking cues from their European counterparts, elite American women chose to get inked to display their daring, adventurous spirits. While their tattoos depicted family crests, portraits of lovers, or nature imagery, these women had only one requirement: that the art could be hidden by clothing.

Society women could easily conceal their tattoos under the clothing that was fashionable at the time. Dresses had high necks, long sleeves, and long hems, providing ample coverage for these proper ladies’ body art. Their tattoos ranged from illustrations of family crests, animals, and flowers to, later on, depictions of their cars.

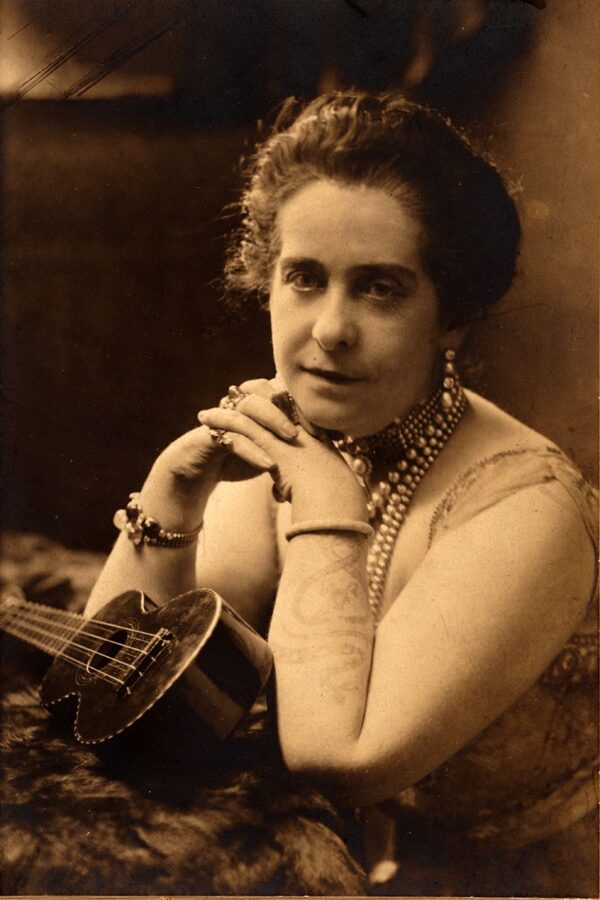

Aimée Crocker

Aimée Crocker, the Sacramento railroad heiress, got multiple tattoos throughout the course of her unconventional, world-traveling life. A woman who cared little for society’s norms, she loved showing off her multiple tattoos.

Born Amy Isabella Crocker in Sacramento in 1864, Aimée inherited $10 million – approximately $232 million today – at the tender age of 10. As she grew up, the eccentric Aimée became a fixture in America’s newspapers, earning the epithets “The Most Fascinating Woman of Her Age” and “The Queen of Bohemia” (as an adult, she changed her name from Amy to Aimée because, she said, it was more exciting). She was well known for her lavish and lascivious parties, her extensive list of paramours, and her commitment to the arts. Aimée married five times, including twice to Russian princes who were decades younger than her, and had five children.

She also traveled the world, spending almost a decade in Asia, where she got most of her tattoos. Her favorite tattoo was the one visible in this picture, featuring two snakes coiled around the initials “J.G.” These letters stood for Jackson Gouraud, her third husband, who many claim was the one true love of her life; he died of tonsillitis in 1910.

Aimée died in 1941. At the time of her death, her full name was Princess Aimée Isabella Crocker Ashe Gillig Gouraud Miskinoff Galitzine, reflecting her full life and world travels.

A Life on Display

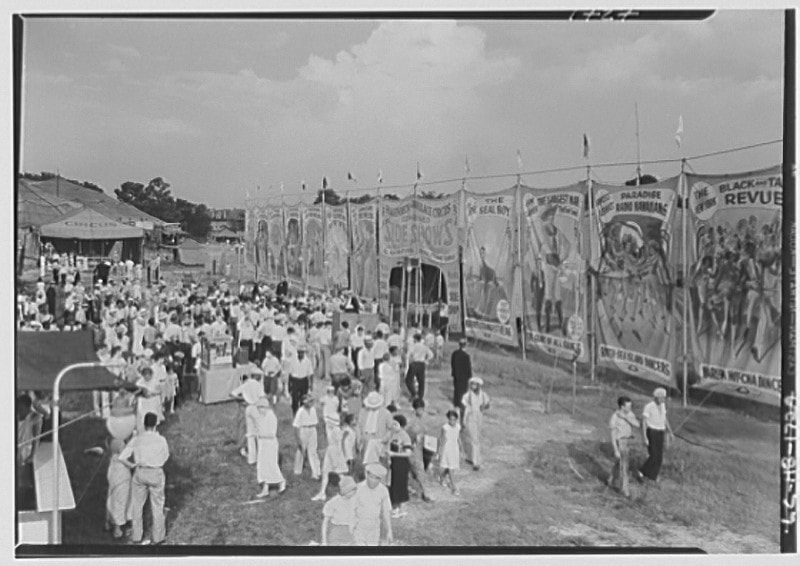

When the first Tattooed Ladies appeared on stage in 1882, they were billed as “living art galleries.”

“Tattooed Ladies,” as these heavily inked performers were called, traveled across the country in circus sideshows (throughout this exhibit, Tattooed Ladies will be capitalized to indicate that this references the women who worked as sideshow performers, rather than simply women who had tattoos). Their presence in sideshows was announced ahead of time in newspaper advertisements, and, on the day of the circus, through huge banners that lined the walkway leading to the sideshow tent.

Primarily working-class women, these Tattooed Ladies were covered with permanent body art from neck to feet. It wasn’t the art that customers paid to see, however. Men, women, and children ogled Tattooed Ladies as they stood on display with other “freaks” in the sideshow.

It would have been a titillating display – these women were fully inked and less-than-fully dressed. But for Tattooed Ladies, presenting their bodies in this way was a small price to pay. After all, they thought, what could be better than getting to travel the country, and even the world, when women had few options outside of marrying and staying home to raise children?

Although Tattooed Ladies’ lives were balancing acts between public display and personal independence, the salary certainly didn’t hurt its appeal. In the 1890s, most working-class families lived on $300 to $500 a year. A Tattooed Lady – especially a well-known one – could make $100 to $200 a week, equivalent to $2,500 today.

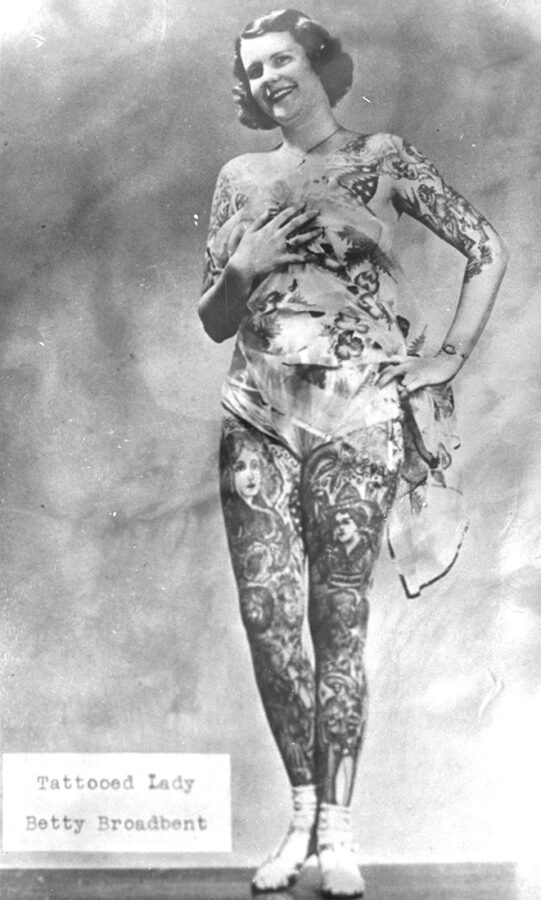

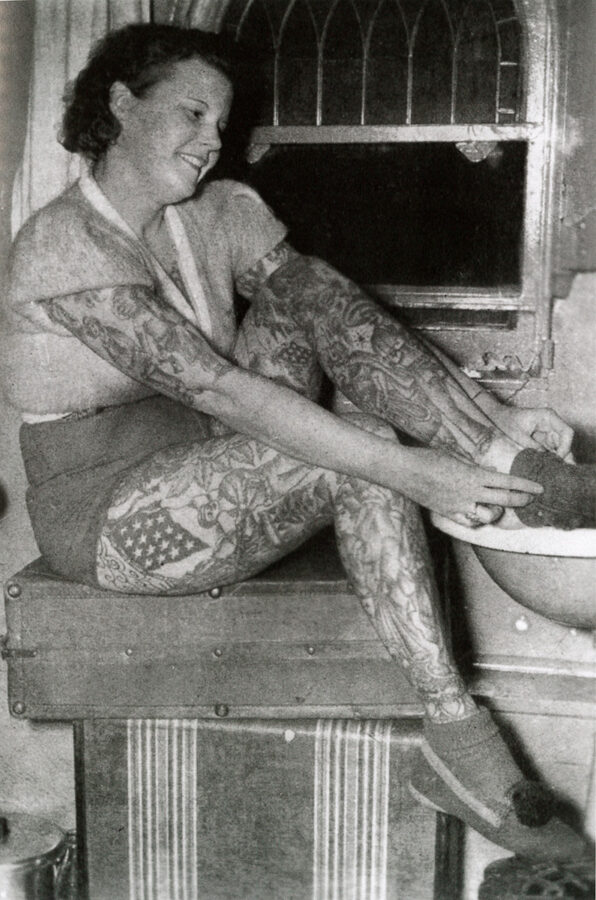

Betty Broadbent was the most famous and beloved Tattooed Lady of all time.

After seeing a Tattooed Man on the boardwalk at the age of 14, Betty Broadbent becamed fascinated with tattoos. She chose to get inked with a variety of images, from portraits of public figures like Charles Lindbergh, Pancho Villa, and Queen Victoria to religious icons like the Madonna and child. She eventually wore over 350 distinct designs.

Betty memorably displayed her tattoos during a beauty pageant at the 1939 World’s Fair to challenge conventional standards of beauty. Sadly, she didn’t win. Until her retirement in 1967, Betty performed and traveled with circus sideshows; in addition to working as a Tattooed Lady, she was also an accomplished steer rider. Although sources differ on this, some consider Betty to be the most photographed Tattooed Lady of the 20th century.

In addition to performing, Betty also worked as a tattoo artist. After tattooing in San Francisco, New York, Montreal, and Florida, Betty became the first person inducted into the Tattoo Hall of Fame in 1981.

Tattooed Ladies crafted stories about their body art to appeal to the masses.

Tattooed Ladies made a personal choice to get inked, but this truth was not scandalous enough to sell sideshow tickets. Playing to Americans’ fascination with the Wild West, many Victorian-era Ladies invented stories of kidnappings and forced tattooing by “savage” Native Americans.

These stories changed with the second wave of performers in the 1920s and 1930s. These women “revealed” that they got inked to secure the affection of a tattooist husband-to-be or to find a life of adventure. These themes of love and independence reflected the changing roles of women in American society.

![An old poster shows a drawing of a bearded, fully-tattooed white man. The headline reads, "Farini's Latest Novelty [at the] Royal Aquarium. Captain Costentenus, the Greek Albanian! Tattooed from head to foot in Chinese Tartary, as punishment for engaging in rebellion against the king."](https://exhibits.exhibitenvoy.org/wp-content/uploads/Captain-Costentenus-Poster-for-Web.jpg)

Tattooed Men paved the way for their female counterparts.

One of the most famous Tattooed Men was Captain Costentenus, seen here. He was covered with tattoos, including his face, scalp, genitals, and finger webbing. The Captain claimed to be an Albanian prince forcibly tattooed by island natives, but historians believe that he got inked for the sole purpose of exhibition.

The popularity of Tattooed Men waned when Tattooed Ladies began to work in sideshows. The women’s risqué clothing and defiance of traditional gender roles made for a much more scandalous – and profitable – display.

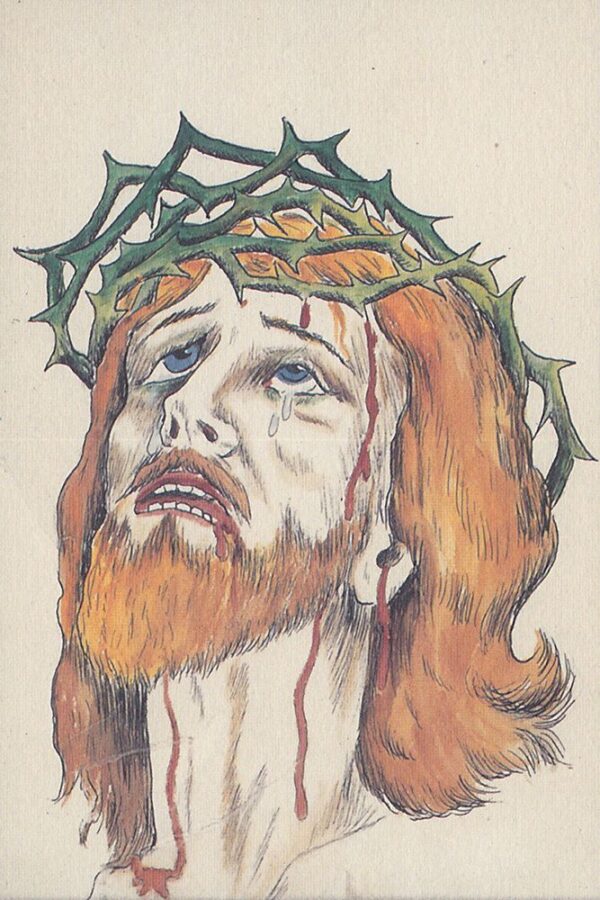

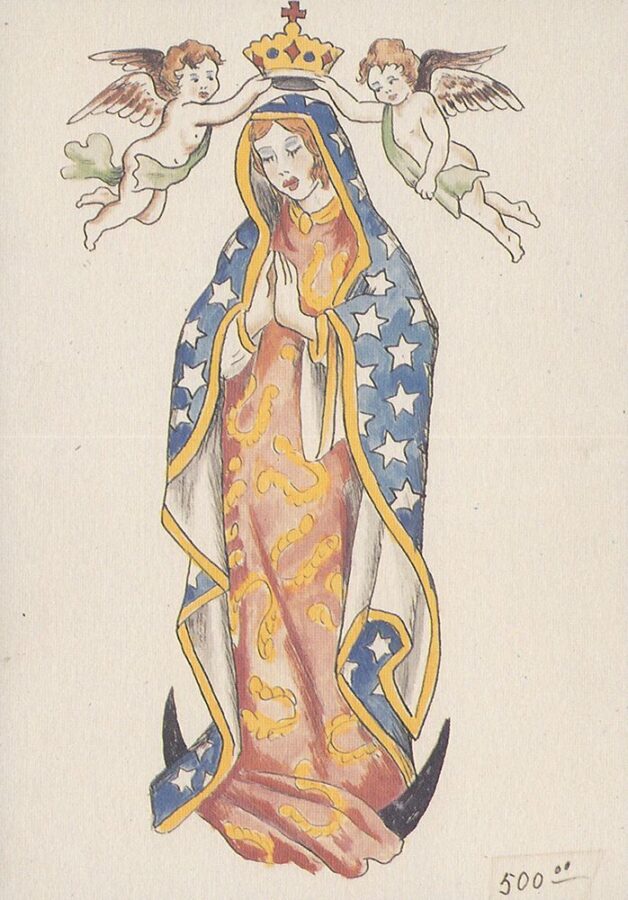

Limited technology, not gender, influenced the tattoo choices of sideshow performers.

Patriotic, religious, and nature-themed designs reigned supreme for heavily tattooed people of all genders. However, the limitations of early equipment created a certain “look” for all tattoos. The first wave of Tattooed Ladies had designs that used heavy black ink, as well as the only other available colors: dark red and navy blue.

By the 1910s, tattoo technology had greatly advanced. Intricate designs in a variety of colors became possible. Lady Viola sported the faces of six presidents on her chest, while Artoria chose to wear her favorite religious imagery. Such icons lent an air of respectability to the Tattooed Lady.

Learning the Trade

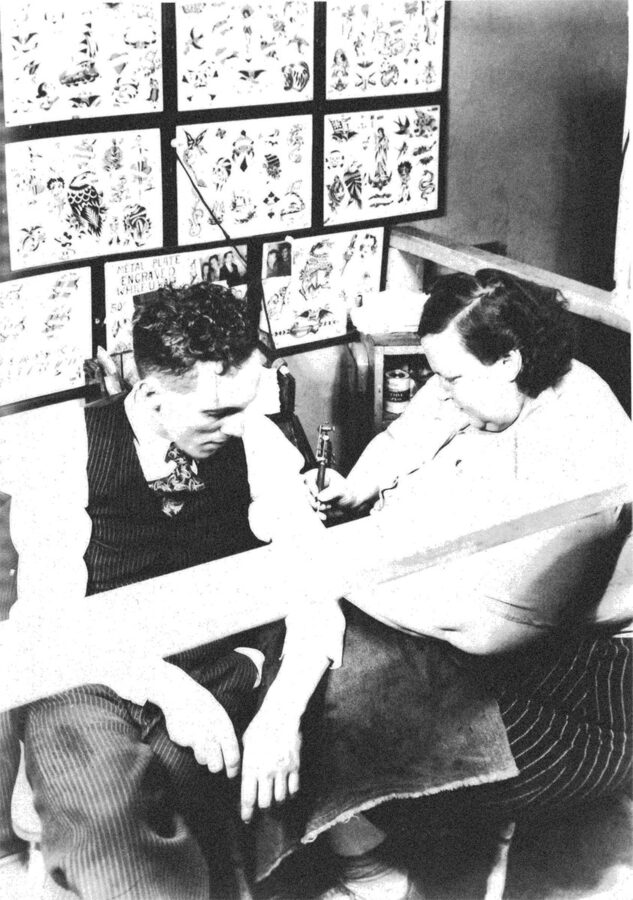

Becoming a tattooist wasn’t easy, especially if you were a woman.

Male tattooists jealously guarded the secrets of “their” trade, worried that teaching other men would create too much competition. Most disliked taking apprentices for this very reason.

It was even tougher for women looking to break into the business. Not only did women have to contend with tattooists’ concerns about competition, but they also had to deal with the sexism entrenched in American society. As such, almost all early female tattooists learned how to tattoo from – and set up shop with – their husbands.

Against the odds, these women established successful careers in California and beyond. Like their male counterparts, female tattoo artists worked in busy port towns like San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego, catering to sailors down by the docks.

From the Sideshow to the Shop

For many Tattooed Ladies, including Betty Broadbent and Lady Viola, exhibiting their bodies on stage was just the beginning. To make ends meet during the circus off-season, performers picked up tattoo machines and shifted the focus from their bodies to customers’ – both men and other women.

Tattooed Ladies of the 1920s and 1930s often worked as tattooists well into old age, ensuring a second career after their performing days were over.

Maud Stevens Wagner was the first non-Native American woman known to tattoo.

A circus contortionist and aerialist, Maud met tattooist and future husband Gus Wagner in 1904 and asked him to “tattoo her all over and teach her to tattoo.” She eventually moved to L.A., where she, her husband, and their daughter Lotteva all tattooed together.

Maud helped pave the way for female tattoo artists in the U.S. Even so, she originally had to advertise her services under the name M. Stevens Wagner, as many men wouldn’t knowingly come to a shop to get a tattoo from a woman.

While there is some evidence of earlier non-Native female tattooists, their names are lost to history.

Madam Austin

Not much is known about Madam Austin, a Californian tattoo artist, except that she worked in a shop with several well-regarded male tattooists in San Francisco.

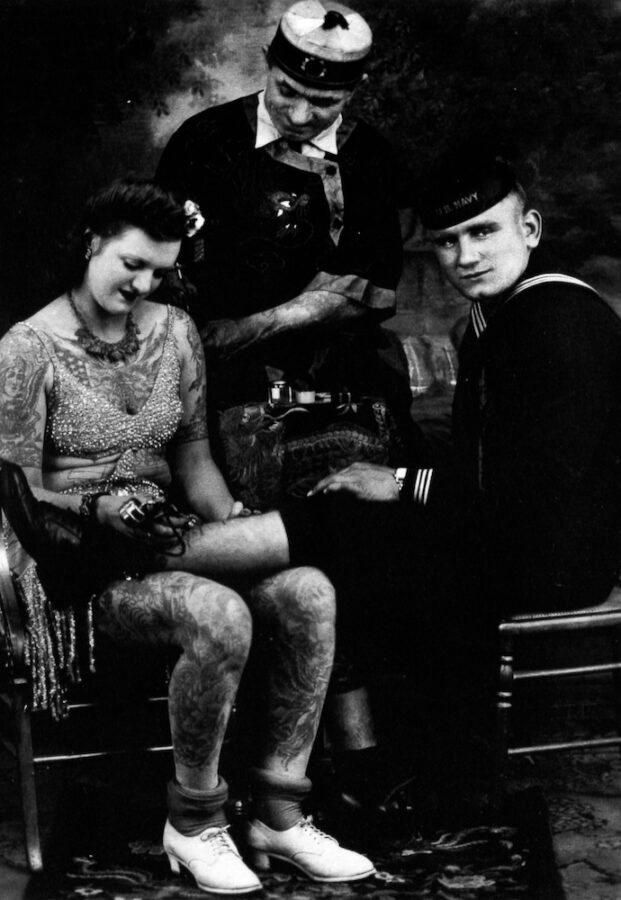

Fellow tattoo artist Irene “Bobbie” Libarry took the never-before-seen photo of Madam Austin here in 1915.

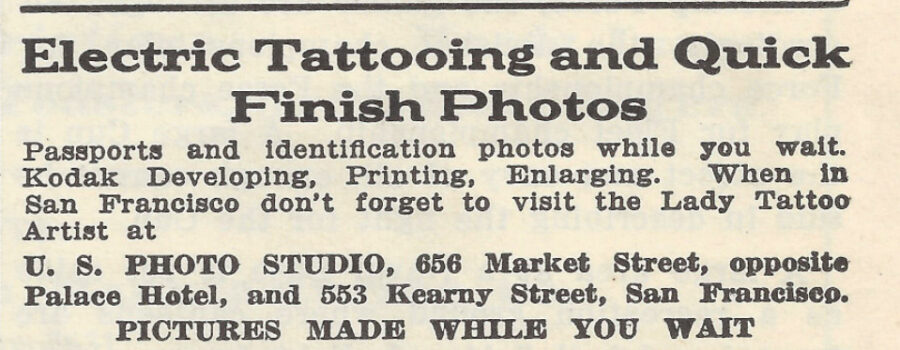

It’s also likely that the “Lady Tattoo Artist” mentioned in this 1915 newspaper clipping was Madam Austin. Her shop would have been located near the Barbary Coast, a notorious red-light district in San Francisco.

Ruth Weyland

Tattoo artist Ruth Weyland worked in San Francisco in the 1930s. This undated photo of Ruth was doctored to make her look heavily tattooed, though the reason for this remains a mystery.

While well-known for tattooing overtly lesbian imagery, like the 1933 design seen here, she also loved to tattoo sailors, calling them “the gems of the earth.”

“Painless” Nell Bowen

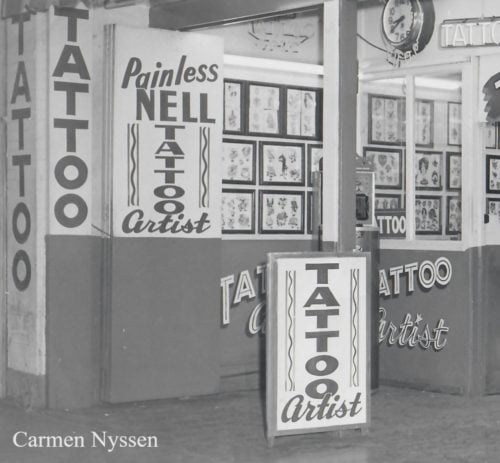

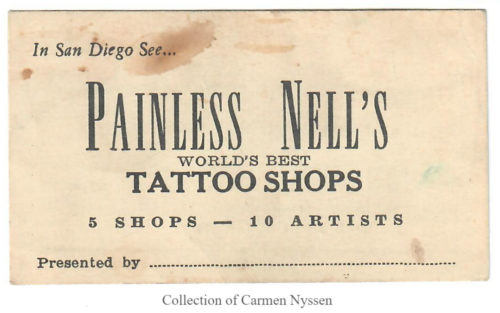

“Painless” Nell Bowen tattooed in San Diego during and after World War II, catering to the city’s large seafaring population. Her many shops monopolized the San Diego tattoo scene.

Nell owned and operated five tattoo shops at one time – a huge feat even today – and employed male and female tattooists. She and her crew worked quickly, inking as many sailors as possible in one day, but often sacrificed cleanliness to do so.

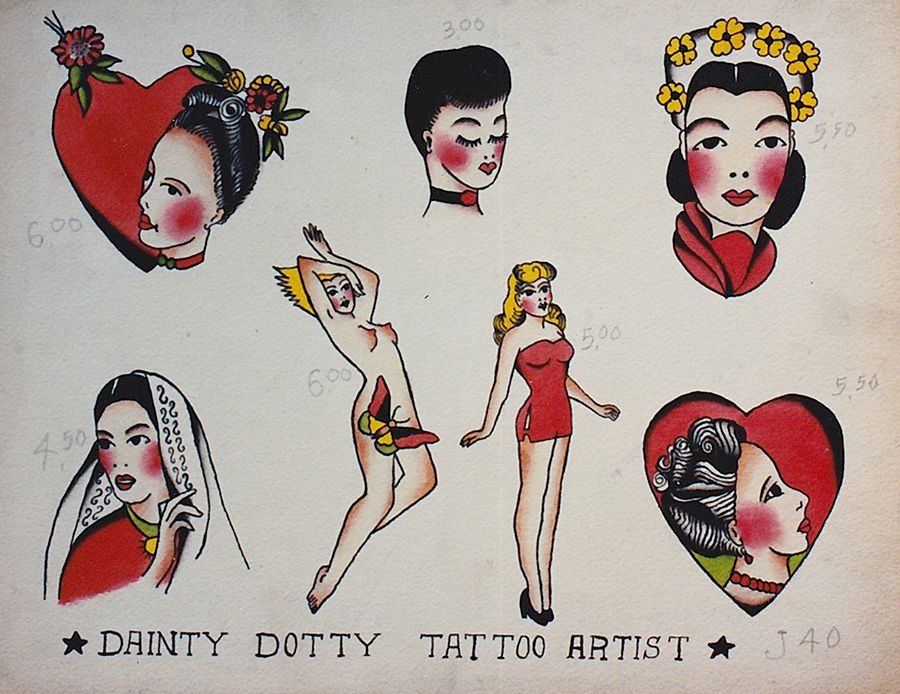

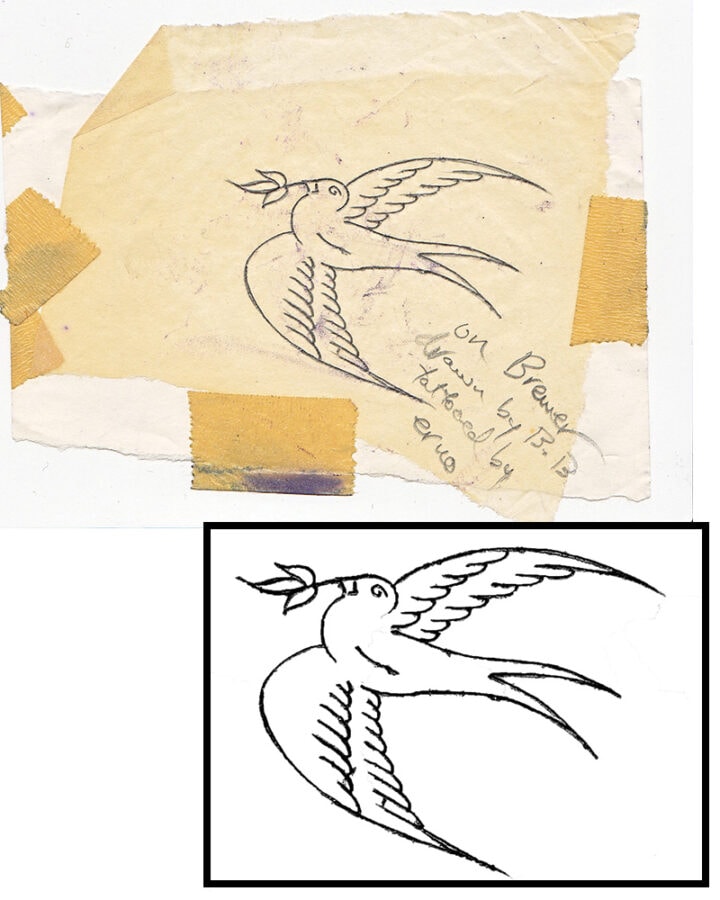

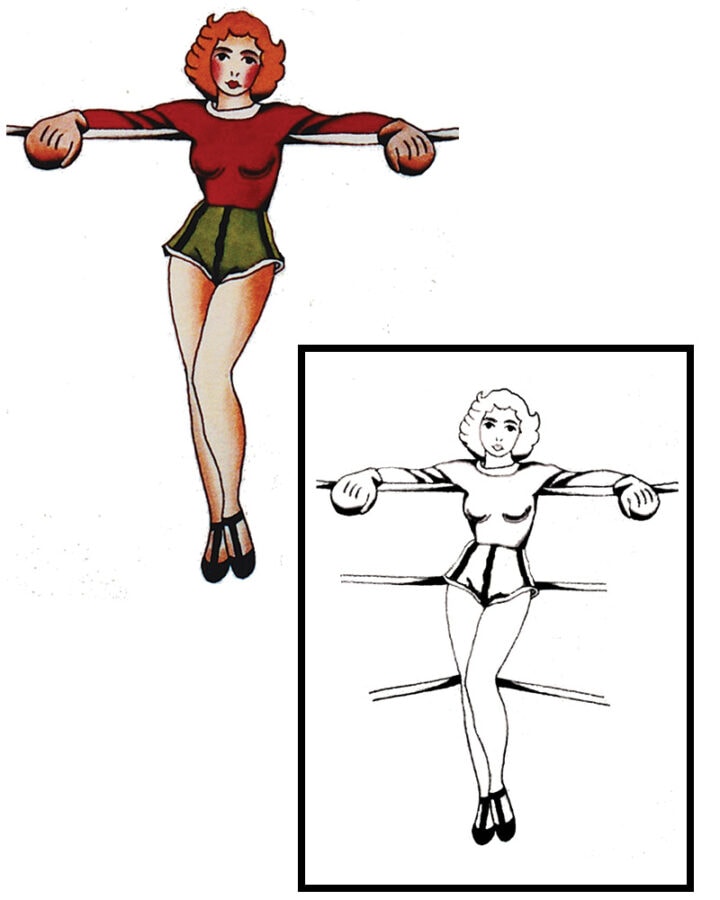

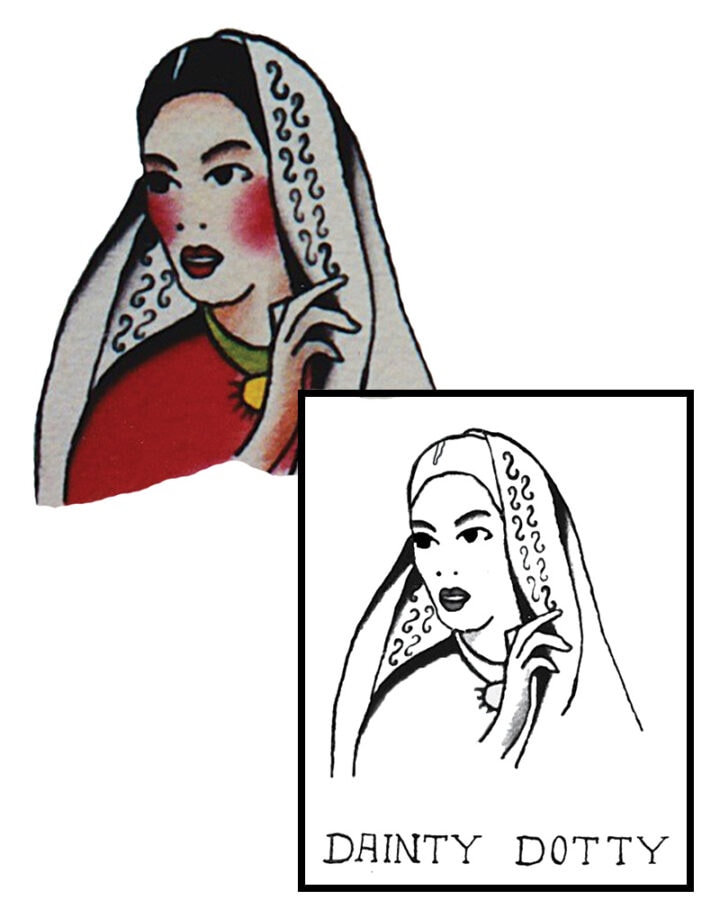

Tattooists often inked their customers with pre-drawn designs known as “flash.”

Both male and female tattooists had a large selection of flash available for customers at pre-determined prices. The quality, style, imagery, and price varied by artist. Though these images were often created by the tattooists themselves, tattooists also used designs by other artists.

Dorothy “Dainty Dotty” Jensen, a former Fat Lady with Ringling Brothers Circus, created two of the sheets of flash seen here. Her tattooist husband, Owen, taught Dotty the trade. They made their home together in Los Angeles after the end of World War II. Lotteva Wagner, the daughter of Maud Wagner (mentioned above), designed the religious flash. Lotteva never got tattooed herself, but was well-regarded in the industry for her work.

The Continuing Story

The Continuing Story of Women and Tattoos

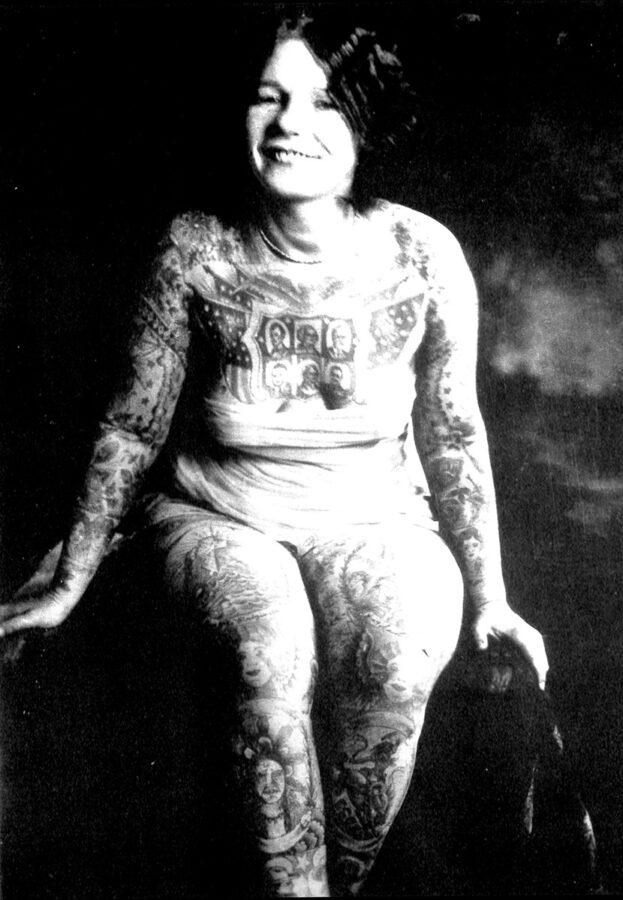

The ominous reputation of tattoos – a perception that still plagues inked women today – grew stronger after World War II. In the 1950s, large numbers of outlaw bikers, gang members, felons, and other social outcasts began getting tattoos. This meant that tattooed women now shone in a less-than-favorable light.

It wasn’t until the late 1960s that there was another tattoo revolution. When rock singer Janis Joplin showed her delicate body art on stage, women across the country clamored for their own. The emerging feminist movement of the 1970s, too, prompted even more women to get inked. Feminists chose to get tattooed to visibly reclaim their bodies and confirm their independence.

Today, tattoos are more popular than ever. But, for how long? As tattooed Millennials and Gen Xers age, will their children want to get inked and look like their mothers? There’s no way to know for sure. But one thing is clear: the future of tattoos will continue to be shaped by its past, and by the tenacious, inked women who staked out their place in California’s history.

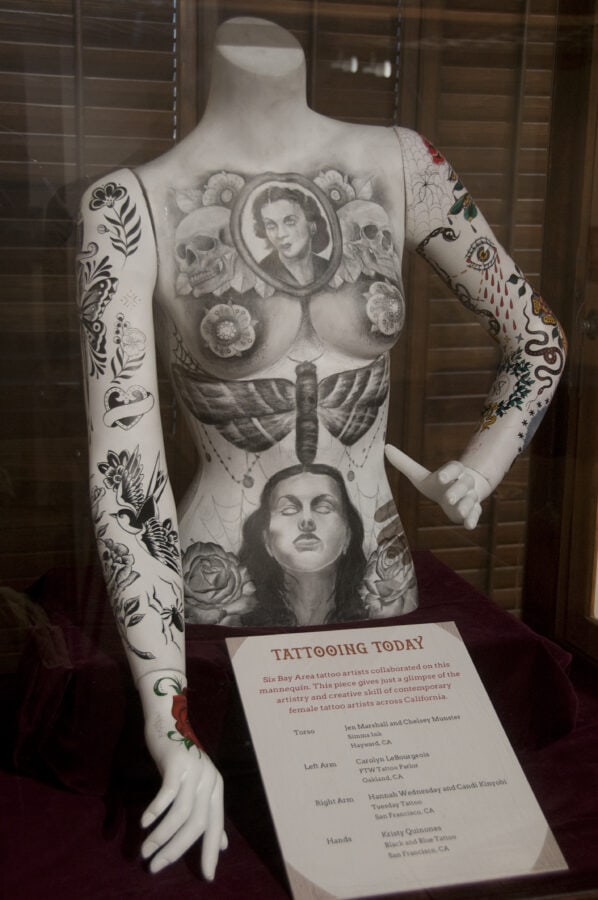

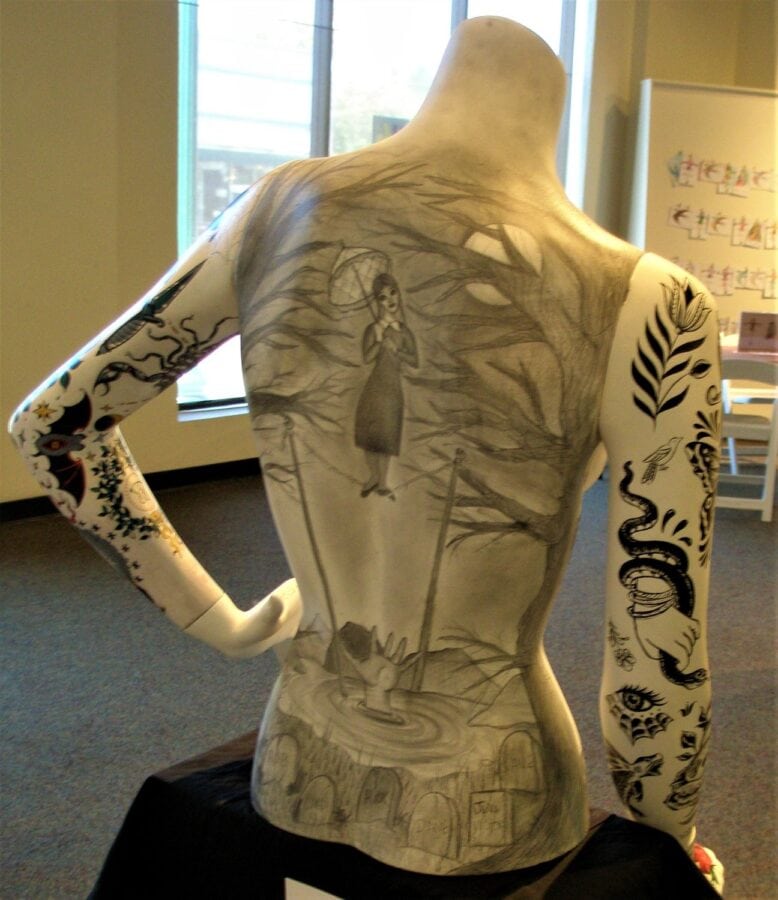

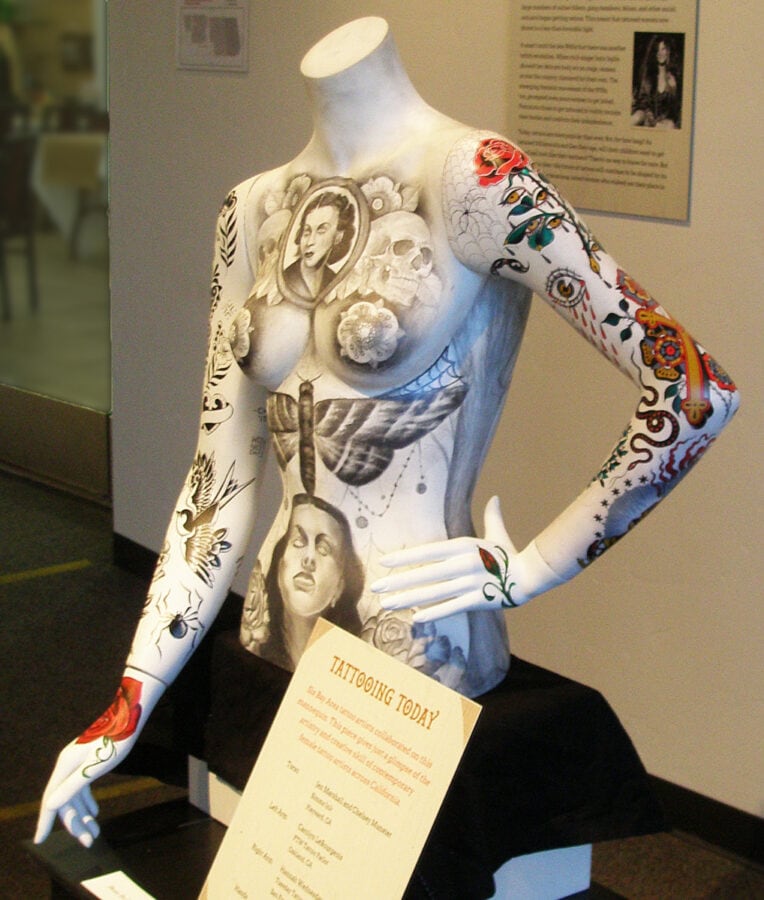

Tattooing Today

Six Bay Area tattoo artists collaborated on this mannequin in 2015. This piece gives just a glimpse of the artistry and creative skill of contemporary female tattoo artists across California.

- Torso: Jen Marshall and Chelsey Munster, Simms Ink, Hayward, CA

- Left Arm (color): Carolyn LeBourgeois, FTW Tattoo Parlor, Oakland, CA

- Right Arm (black and white): Hannah Wednesday and Candi Kinyobi, Tuesday Tattoo, San Francisco, CA

- Hands: Kristy Quinones, Black and Blue Tattoo, San Francisco, CA

Explore More

Color It In: Tattoo Flash

Tattoo artists often separate the tattoo process into three steps: outlining the design in black ink, shading for dimension, and adding in color.

Try your hand at shading and coloring flash – pre-made tattoo designs – by Betty Broadbent and “Dainty Dotty” Jensen, two early female tattoo artists.

Piece It Together: Maud Wagner in Color

This puzzle features a colorized photograph of Maud Wagner, one of the female tattoo artists you met in this exhibit. To view the full photo, click on the square white icon with two small mountains.

Colorized photo by Reddit user u/SteelballJohnny. Original photo from the Library of Congress.

Leave a Comment

What’s your tattoo story?

No matter how you identify, we want to know the story behind your tattoo. Tell us a little bit about yourself and the reason you got inked. Don’t have a tattoo? Tell us why…or about your plans for a future design.

Please note: after you post your comment, the webpage will automatically refresh and then return you to this section of the exhibit.

What’s your tattoo story?

Thank You

Thank you to the Dennis + Leslie Power Library, Laguna College of Art + Design for hosting this exhibit.

To find out more about Laguna College of Art + Design, visit their website.

Thank you to the following people and organizations for their funding and support of this exhibit: Hayward Area Historical Society, History San Jose, and Adrienne McGraw and Susan Spero at John F. Kennedy University. We are especially grateful to Lyle Tuttle for sharing his knowledge and stories of female tattoo artists with the curator, and for his support of this project before, during, and after its first installation in Hayward.

Extra special thanks to the Kickstarter backers who brought the traveling version of this exhibit to life: Hideko Akashi, Austin Beer, Heather Bouchey, Mary Bourke, Brittany Bradley, Alida & Todd Bray, Peter Castillo, Monica Chew & Chris Karlof, David Cohen, Laura Cohen, Lori Cohen, Jonah Comstock, Ivan Cooper, Ofer dal Lal, Bill Dalzell, Brian “Fred” Danaher, Mary Danaher, Rose Danaher, Brian Davidson, Cara Dodge, Jordan Evins, Sara Flynn & Don Libbey, Mark Foster, Michael Fox, Joe Franke, Ellen & Bob Freeman, Aeron Tynes Hammack, Tamara Hayes, John Heylin, Jessica Hicks, Alexandra Higgins, Lesli & Rob Hobart, Alexander Jackson, Robert & Joyce Kleiner, Kelly Kunaniec, Shyam Lal & Rami Randhawa, Jackie Larson & David Schoenstein, Terri Le, Ryan LeBlanc, Mary Anne Longpre, Katherine Lord, Sarah Marsom, Mitzi Mathews, Chelsea Matthews, Adrienne McGraw, Alec McMullen, Gale & Ross Miller, Sarah Moir, Dave Oshry, Triana Patel, Kathy Patterson & Joe Boboschi, Michelle Powers, Candice Rankin, Eleanor Sandys, Jennifer Spotswood, Bob Stern, Cindy Stern, Kat Sullivan, William Wild, Colin Williams, and Dennis Yang.

What others are saying:

My favorite tattoo is a Leonard Cohen drawing. My dad loved Leonard, so I grew up listening to him, and eventually he became one of my favorite artists.