Presented by YOUR MUSEUM

Multiply by Six Million is a project by Evvy Eisen and toured by Exhibit Envoy. All photographs and writings are © Evvy Eisen unless stated otherwise. This online exhibition is adapted from the physical touring exhibition.

Introduction

“This is important. This is what happened to me and to my family. It should not be forgotten…”

“Multiply by Six Million: Portraits and Stories of Holocaust Survivors” presents the Holocaust on a human level, as thirty-eight survivors recall their experiences before, during, and after one of the greatest tragedies in human history.

For fifteen years, Evvy Eisen photographed and collected the personal narratives of Holocaust survivors living in the United States and France. During the course of the project, Eisen completed over two hundred portraits. Many of these survivors have since passed away, but their legacy lives on.

Eisen’s images and the stories from each survivor vividly portray the power of human courage in the most desperate circumstances. They are also a testament to the productive lives Holocaust survivors created and their continuing commitment to fight prejudice and injustice. From these portraits and stories, we can be inspired to stand up for those who are targeted today, and to unite against the dehumanization of all men, women, and children.

It is only through personal connections that we can understand the true meaning of such events and prevent them from happening again.

Evvy Eisen, photographer

Multiply by Six Million is a project by Evvy Eisen and toured by Exhibit Envoy. Eisen’s work is in private and museum collections in Europe and the United States, including the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC, the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, and the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris. For additional information about the photographer and her work, visit evvyeisen.com. For more information about this project, visit the Multiply by Six Million project website. In addition, this site features The Survivor Research Archive: Eisen’s complete collection of portraits and survivors’ full texts of their wartime experiences, organized by category.

For more information about hosting this exhibit in an online or physical format, contact Amy Cohen, Executive Director at Exhibit Envoy, at [email protected].

Navigating the Exhibit

In this exhibit, you will meet 38 survivors of the Holocaust. To view each survivor’s full story, simply click on the button that says “Read More About…” Start your journey here with Martin’s story.

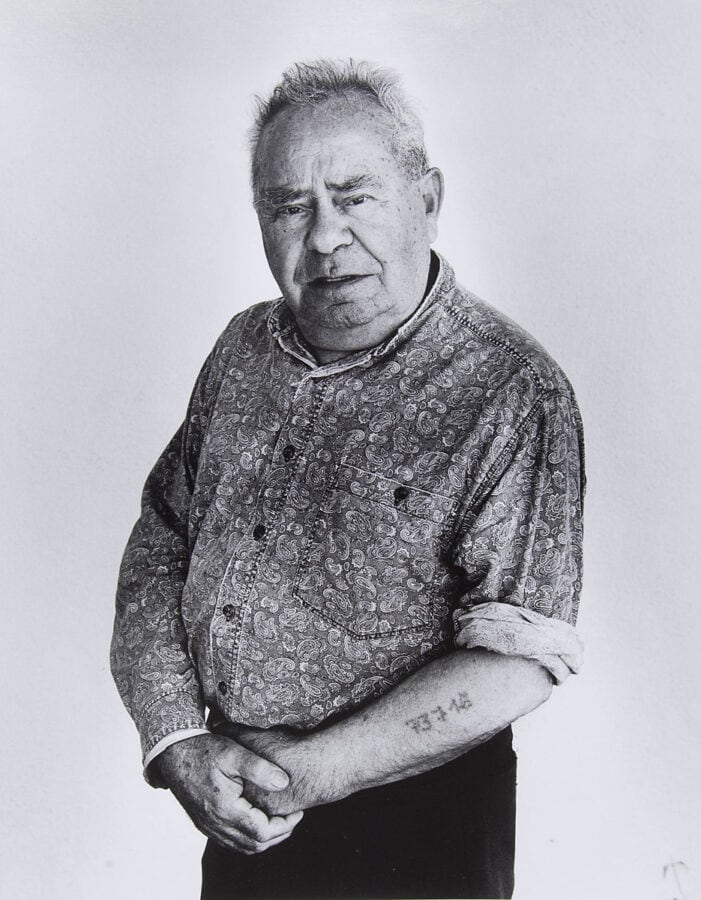

Martin Kahane

Martin Kahane and his entire family were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

I remember when the tanks came into our town – seeing the soldiers in the streets carrying rifles. There was a curfew and the first person I ever saw killed died because he was out after the curfew. He was running and the Germans shot him.

Martin Kahane was born in Ciechanow, Poland in 1923. He lived with his parents, five brothers, and one sister. Ciechanow was a small city in which there were few non-Jewish Poles. Martin’s father was a salesman traveling by horse and cart. His mother took care of the large family, and Martin attended school.

In 1939, the Germans invaded Poland and instituted many restrictions for the Jewish population. At first, the family remained in Ciechanow, and where they were forced to work for the Germans. Three years later, the Germans loaded the entire family onto a train and transported them to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Upon their arrival, Martin’s mother, father, and brother, David, were separated from the rest of the family. Martin never saw them again.

Martin’s sister was grouped with other younger women, and later died in the camp. Another brother, Avram, had been deported to Auschwitz separately with his wife and child, where they all died. Martin, however, remained with his brothers Sidney and Sam. The number 73718 was tattooed on his arm; Sam’s number was 73719, and Sidney’s 73720. At one point, Martin contracted typhus; he was sent to the camp hospital, where the notorious Dr. Mengele examined him.

In Auschwitz, Sidney was assigned to work with recently arrived transports, Sam worked on sewer lines, and Martin made windows and doors for new homes for German officers.

When the end of war was near, Martin was transferred to a camp in the German village of Buchberg. Eventually, Martin reunited with his brothers Sam and Sidney in the camp, and the American forces liberated them.

After the war, Martin went to Israel on his own. He joined the army there and was decorated for his service in the war for independence. In 1950, he rejoined his brothers in Germany and they immigrated together to the United States, eventually settling in California. Martin worked as a machinist and also operated a laundromat. Married and divorced, Martin was the father of two sons and two daughters. Martin did not raise them to be Jewish, explaining that he lost his faith in God from the war.

Definitions

In this exhibit, you’ll encounter specific words related to the Holocaust. Some definitions follow.

This content is only available in the full online exhibition.

The Multiply by Six Million project was partially funded by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, California Humanities, and the Koret Foundation.

Searching for Refuge

Lotte Stein

Lotte and her family escaped from Austria and spent the war years in England.

Lotte Stein (née Pfeffer) was born in 1921 in Vienna. Her father Maximilian, the owner of a bicycle factory, and her mother, Martha, had considered themselves assimilated Jews. After her mother’s death, when Lotte was seven, she and her older sister were raised mostly by servants, simple and devout Christian women from the countryside. Lotte was not taught about her religious heritage and traditions, but felt that she was different from most of the people around her.

The family had not believed the rumors coming out of Germany at the time, and were sure that those kinds of atrocities could never happen to them because they were Austrians and had blended into the Viennese culture. But when Hitler entered Austria in 1938, they were confronted with the fact that they were Jewish. They suffered the many deprivations and restrictions that the Nazis imposed on the Jews; Jews were forbidden to enter restaurants, coffee shops or sit on benches in the park. They were not allowed to use public transportation and the family car was confiscated. Lotte had to move to the back of her class and, after a few months, was forbidden to attend school all together. She was in constant fear of being arrested and deported.

After living for a year under Hitler’s occupation, Lotte, her father, and her sister were able to utilize family connections and leave for England where they survived the war years. However, they were considered enemy aliens and undesirable subjects, and were not trusted to contribute to the war effort. They were dependent upon refugee organizations, and could obtain only menial jobs. Her grandmother, aunt and uncle were not able to leave Austria in time, and died in concentration camps.

My life had become a journey of searching and finding the essence of myself. I felt much more at home in the American multi-cultural society. I felt drawn to the Jewish community and slowly found my way back to my heritage.

In 1946, Lotte immigrated to America where she married and had two daughters. Lotte was drawn to the Jewish community, slowly finding her way back to her Jewish heritage. Determined to resume the studies she had to abandon in 1938, she earned master’s and doctorate degrees and had a career as a Family Therapist.

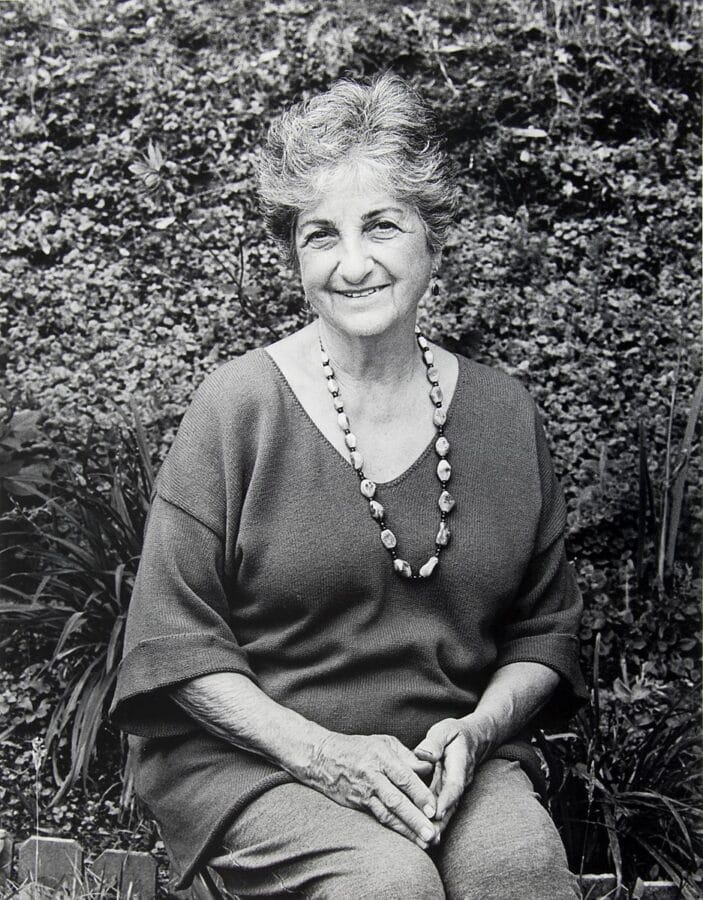

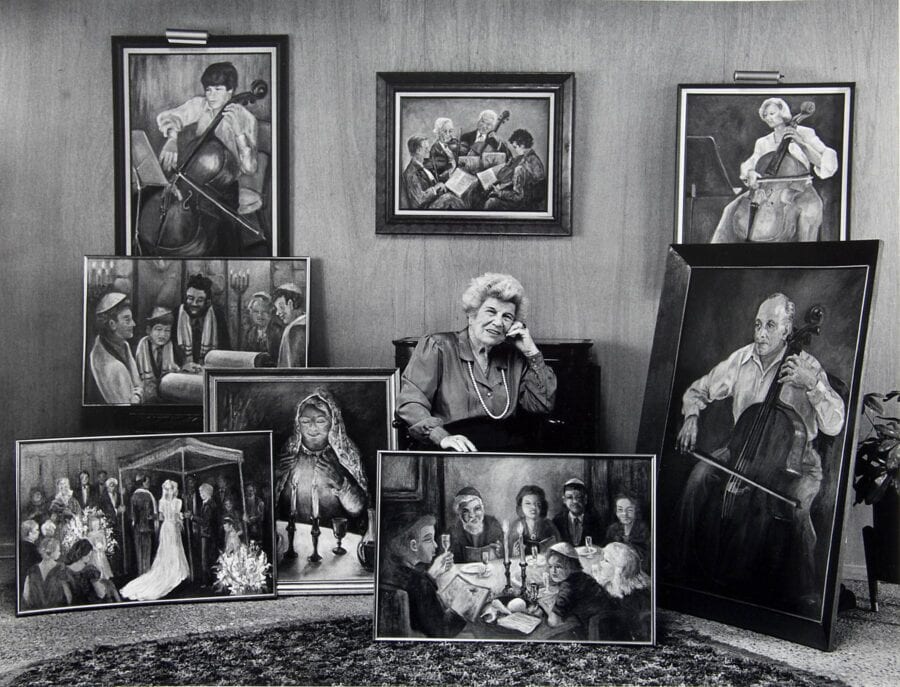

Ruth Geoffey

Ruth Geoffey escaped the Nazis by fleeing to Manila, where she spent the war years.

Ruth Geoffey (née Huber) was born in 1915 in Brünn in the former Czechoslovakia. At the outbreak of World War I, the Austro-Hungarian army recruited her father, an officer at the time. Her parents divorced when she was two, and her mother took young Ruth to her family in Berlin, where Ruth grew up.

When Hitler rose to power in 1933, Ruth had just finished high school, but the new laws made it impossible for her to attend university. Regardless, Ruth’s family encouraged her to develop her talent for drawing, and she went to art school. Ruth illustrated stories for Jewish papers and worked did fashion design.

Ruth married Joseph Reiner, a journalist, in 1938. Together, they made plans to immigrate to Shanghai.

We left by train on Christmas hoping that the guards would be more lenient because of the holiday. The couple we were traveling with was taken away and was never seen again.

Ruth and Joseph arrived safely in Trieste, Italy with all of their hidden “treasures,” which allowed them to survive until their ship for Shanghai sailed. After Shanghai, they went to Manila. Despite carrying Austrian passports with a “J” marking them as Jews, they were considered “Allies of the Axis” and were not interned.

Life was very difficult for the Jewish refugee community in Shanghai, which was under the leadership of a Rabbi who had escaped from Germany. Because of tremendous inflation, the couple was forced to sell most of their belongings and plant gardens to eat; this garden became their main source of food. During the war, Ruth secured a travel ticket to Shanghai for her mother, who successfully fled to Asia. No other members her family in Czechoslovakia and Germany survived.

When her husband died in 1945, Ruth remained in Manila. There, she married a Holocaust survivor who had been in several concentration camps. Ruth taught arts and crafts at the American School in Manila, while her husband worked for 20th Century Fox film. They eventually moved to California, where Ruth started painting and received a degree in Fine Arts in 1968.

Later in life, Ruth used her art to paint subjects recalling past times and reviving memories of Jewish traditions. Those topics are the origins of her many paintings surrounding her in her portrait.

Gerda Levy

Gerda’s family escaped Europe and spent the war years in Bolivia and Argentina.

Gerda was born in Breslau, Germany, in 1925, the only child of Georg and Gertrud Bielski. Her father, a well-established businessman, had fought for the German army in World War I. He felt that he was a German first and a Jew second, and that he had nothing to worry about.

When Gerda was 13, SS troops burst into the classroom of her Jewish school and murdered the teacher in front of the students. It was to be the last day of Gerda’s formal education. Her parents attempted to get visas to leave Germany, but it was too late. Their funds were confiscated and their situation began to look hopeless.

My father had hidden in a neighbor’s house when the soldiers approached. My mother and I watched as the SS men threw my piano out the window, and then, piece-by-piece, all of our furniture followed. Our home was destroyed.

An aunt in Switzerland sent money, which Gerda’s father used to purchase counterfeit visas and tickets on a ship scheduled to leave Europe; that voyage was cancelled. The next ship on which the family had reservations also cancelled their tickets the night before sailing. They received a telegram saying that ship had burned at sea a few days later. They finally obtained passage on a ship sailing from Genoa. After two days of waiting with neither food nor water, they boarded and were crammed into a cabin with about fifty other people. There was little to eat during the entire voyage, but at last they were leaving Germany.

Upon the family’s arrival in Chile, officials discovered their counterfeit visas, but a Jewish organization arranged for the family to land and continue on to La Paz, Bolivia. When the government announced that too many immigrants were living in La Paz, they had to move to a small village in the interior of the country. There, they opened a primitive hotel and restaurant.

Three years later, Gerda left to move to the city on her own. She met and married a photographer who was twenty years older than she was. They crossed the border illegally into Argentina where Gerda worked in a photography studio and took boarders into their home.

Gerda eventually moved to California where she became a successful businesswoman owning a chain of photography studios.

Additional stories are only available in the full online exhibition.

In the Concentration Camps

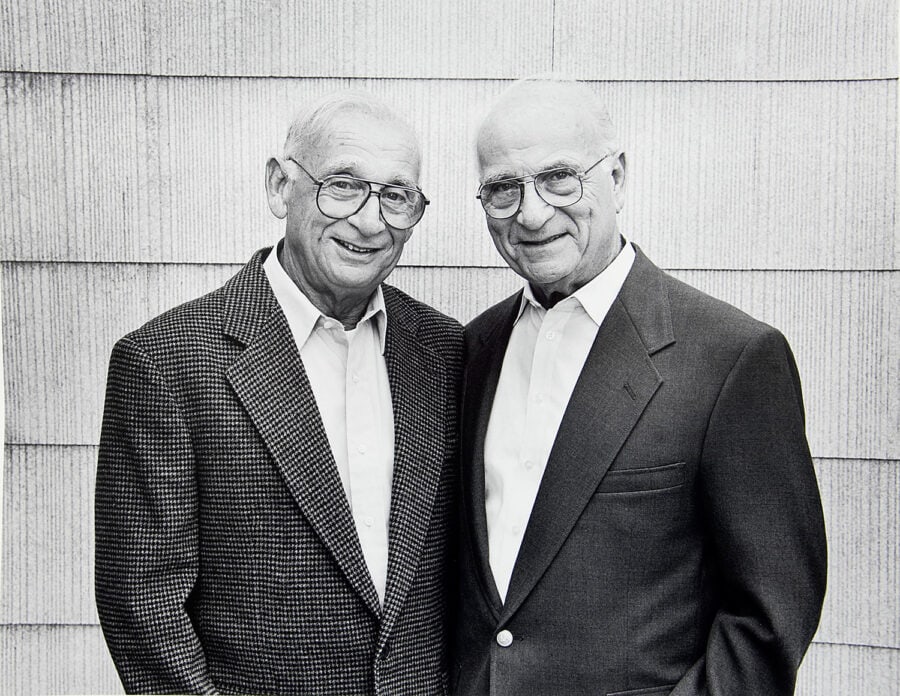

Ernie and Erwin Levy

Brothers Ernest and Erwin Levy were both imprisoned in Auschwitz and other camps. Neither knew the other had survived until after the war.

Beginning in 1934, I was the only Jewish boy in my class and it became impossible for me to study. My teacher was an active Nazi and I was beaten and kicked on a daily basis.

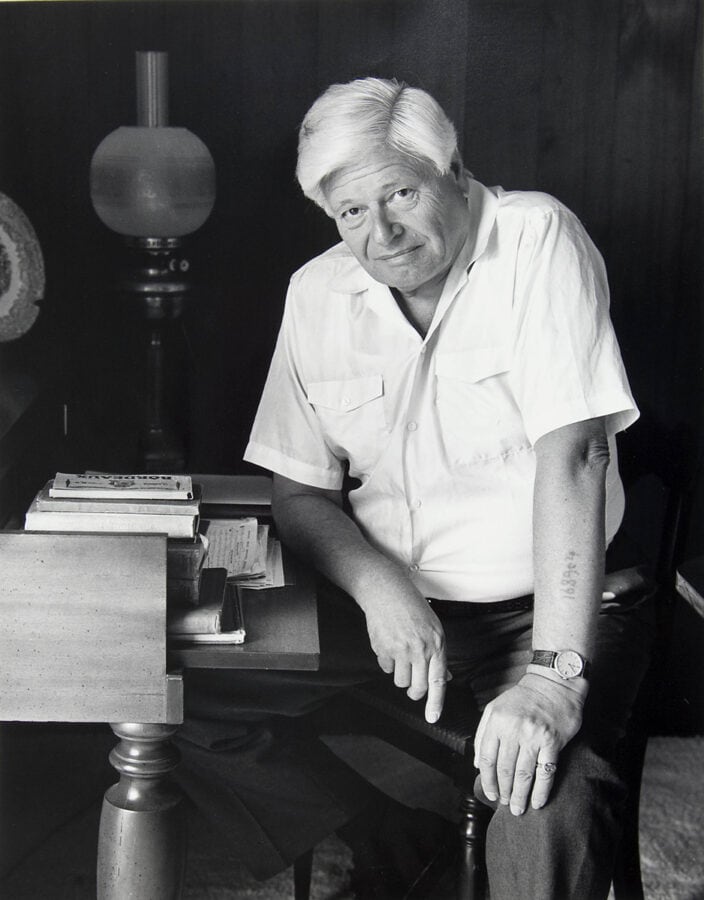

The Levy brothers were born in the small German town of Waldbreitbach (Erwin in 1921 and Ernest in 1925). Their parents were well-educated and, for several generations, the family made a good living as cattle dealers.

In 1938 – one week before Kristalnacht – the family moved to the large city of Cologne. In 1941, the family was sent to the ghetto in Lodz, Poland, but shortly after arriving, they were all separated.

Ernest was taken in a cattle car to Auschwitz. From there, he was sent to Dachau to perform heavy labor, unloading railroad cars digging ditches and building railroad tracks. Just before the liberation of Dachau, Ernest and all the other prisoners who were still able to walk were sent on a Death March into the Alps to be traded for German prisoners of war. Only a handful managed to survive.

Erwin was sent to Posen, and then to Auschwitz; there, he worked as a mechanic and labored in the coal mines. Near starvation, he stole oats from the horses to have some food to eat. Like his brother Ernest, Erwin was sent on a death march, but was liberated by the American Army a week before the war ended.

The brothers had been separated all during the war, and each feared that the other had died. They had a joyous reunion when Erwin traveled to a hospital in Cologne for returning deportees and found Ernest there recovering from typhoid fever. Their parents did not survive and their sister Ruth had disappeared without a trace.

Ernest and Erwin both immigrated to the United States, eventually settling in California. Each man married, continued their education, worked, and created their own businesses.

Once they were reunited, the two brothers remained close for the rest of their lives.

Roma Barnes

Roma Barnes survived several slave labor camps. Her parents and brother were killed in Sobibor.

Roma Barnes (née Rozenman) was born in Demblin, Poland in 1930. Roma’s father’s family owned a sawmill in the town, and she had a happy childhood with a large extended family nearby. When the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939, Roma and her family hid in the nearby forest. When they returned to the town it was occupied.

Roma believed that her family was not as immediately impacted by the occupation because their sawmill was half-owned by a Pole. But, during Passover in 1942, all of the Jews in the town were rounded up in the town square. Her mother told her, “Run! You have to survive!” Roma hid in a Polish farmer’s outhouse, and when she returned to the town, her family was gone.

I came back to the town. I saw friends, people I knew, dead…the doorways, the well, blood was streaming out. My parents and brother were gone…I was alone.

Roma’s survival depended on not looking Jewish and not having an accent when she spoke Polish. She escaped many roundups but eventually was captured with some of her relatives. Roma was sent first to a labor camp, where she worked with other young people in the fields. Roma was transferred to other camps, and remembered how the Germans took some of the children and threw them into a hole they had dug and then threw grenades in. At camp Hasag, an ammunitions factory, she worked making shells until being liberated there by the Russians in January 1945.

The Jewish Refugee Committee was responsible for children who survived the war. They placed Roma in an orphanage in Lodz, Poland and sent her to Czechoslovakia, then to Scotland, and finally to England, where she went to school and worked for seven years. There, she met and married an American, eventually moving to California and raising a family.

Eventually, Roma learned that, along with 2000 Jews from her town, her parents and brother had been taken to the death camp Sobibor in one of the first transports and were all gassed. Of her large extended family, only a few aunts and cousins were alive after the war.

The Menorah in her portrait has been in Roma’s family for 300 years. Buried for protection, it was uncovered after the war by her Aunt Eva.

Leah Laskowski

Leah Laskowski survived the Lodz ghetto, Auschwitz, Stutthof, and a death march.

Leah Laskowski (née Russ) was born in 1912 in Warta, Poland, one of seven siblings. The family moved to Lodz in the mid-1930s, and when the war broke out, they were sent to the ghetto there.

In June 1944, 32-year-old Leah, her mother, and her two sisters were herded into cattle cars and sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. SS guards ordered the prisoners to make two columns. Leah and her two sisters were directed to the right. Their mother, in the left column, was sent to the gas chambers. Leah remembered hearing her mother scream “Don’t run after me. You are still young. Live. Live. Save yourselves.”

After being stripped and having her head shaved, Leah and her sisters were given coarse rags to wear and marched barefooted to barracks. Eventually, Leah was sent to Stutthof concentration camp where the conditions were brutal and where, just for fun, the officers would beat them. Almost a thousand women occupied each barrack, sleeping on wooden planks. They had no sanitary facilities and their clothes were full of lice. Every day hundreds died of starvation and typhoid.

We had to be counted in the yard every morning no matter how we felt, no matter what the weather, rain or cold or snow or wind. Sometimes the count lasted for hours until they got it right. It could never be right because some of us had already died.

In March 1945, the surviving prisoners were marched out. They walked for days, many dying from starvation and exhaustion. They were locked in barns at night, sleeping on wet straw and at one place, a Nazi guard knocked Leah down, leaving her for dead.

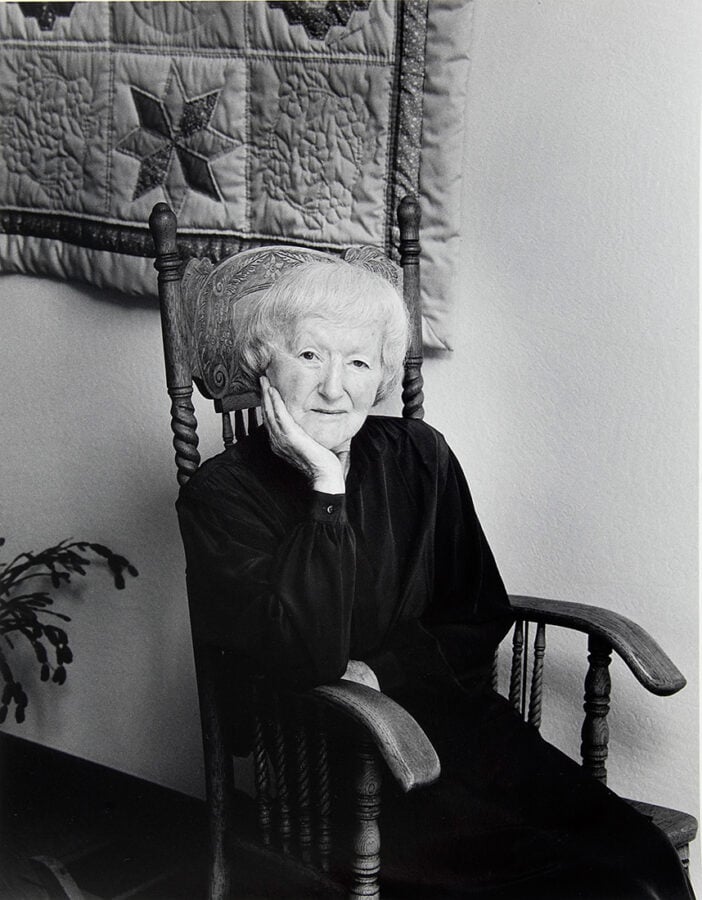

When Leah returned to Lodz after the war, she learned that that the rest of her family had been killed. She then went to Warta, where she married Michael Laskowski. He, with the help of a teenaged Polish neighbor named Dominik Michalak, had escaped the Nazi roundup, and hidden underground for more than four years. Leah, Michael and their daughter Miriam immigrated to the United States in 1950. She chose to be photographed with a pillow she made in a German Displaced Persons camp after the war, and a quilt she created years later in California.

Sam Reselbach

Sam Reselbach worked as a slave laborer at camps in Nazi Germany and occupied Poland. He was the only one of seven children in the family to survive.

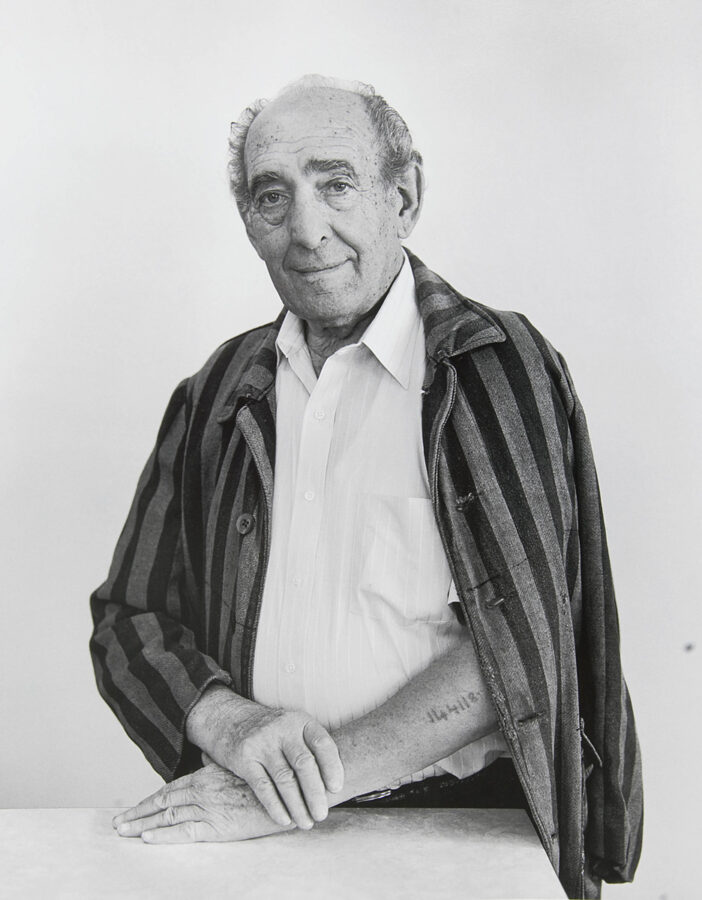

In my portrait I am wearing the jacket I wore in Auschwitz. It was my shield. I put a cement bag under the coat so the water would not seep through. When we were liberated, I kept the coat.

Sam Reselbach was born in Lodz, Poland, in 1919. His father was a painting contractor, and Sam began working as a painter when he was fourteen. In 1941, Sam’s family was sent to the Lodz Ghetto, but the Nazis quickly assigned 22-year-old Sam to work camps. There, he did heavy labor, dragging tree stumps and heavy sacks of cement to build a highway.

Next, he and ~2,000 other men were transported in cattle cars to a labor camp near Berlin, where they procued munitions. It was dangerous work with heavy machinery, and the graphite emitted during the process tore up Sam’s lungs.

In September 1943, all of the men working in the factory were deported to Birkenau. The train journey in a cattle car lasted five days. Of the original 2,000, only 205 remained. Upon arrival, they were undressed and their belongings were taken away. They were all supposed to be gassed, but at the last minute they were spared. Sam was tattooed with the numeral 144118.

At the end of 1944, he was evacuated from the Buna camp and forced to march over 20 miles, all at night and in the snow. After another transport to Camp Dora, deep in Germany, he worked in the tunnels in which the V1 and V2 rockets were produced. Finally, Sam was sent to Bergen-Belsen, where he was liberated by the British Army.

After the war, Sam remained in Germany, where he met and married a Theresienstadt survivor. They immigrated to the U.S., living in California where Sam worked as a painting contractor. When his first wife died, Sam married a longtime friend who was also a Holocaust survivor.

All the other members of Sam’s large family were gassed in Auschwitz. The names of his parents, Abraham and Sarah; his brothers, Schelomo and Pesach; and his sisters, Rifka, Anna, Tauba, and Luba; are all engraved on a tombstone in California.

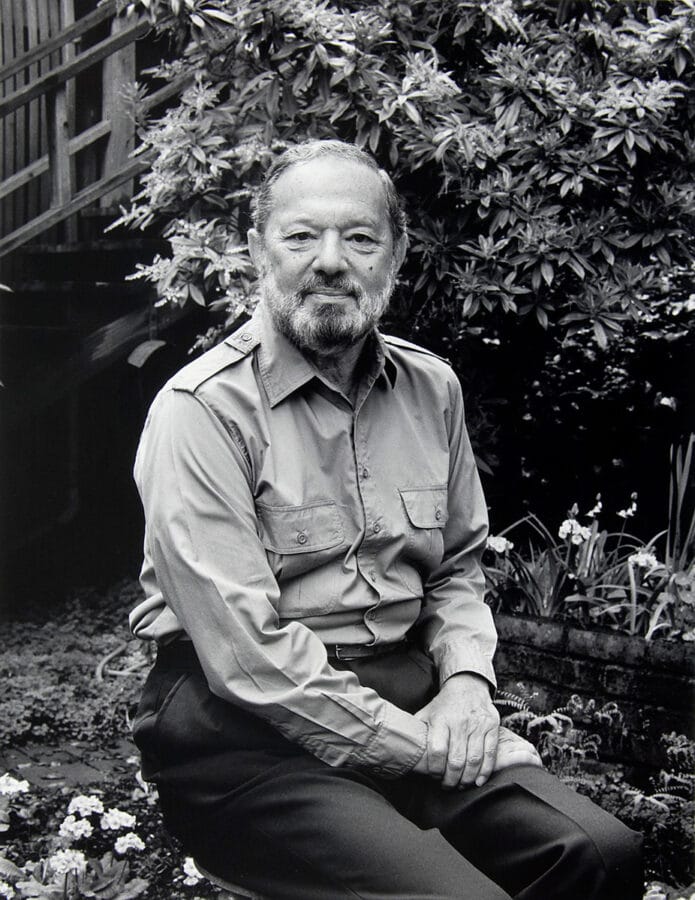

John Steiner

John Steiner survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Dachau, and the slave labor camps Blechhammer and Reichenbach.

Most of my relatives and friends perished in death camps. I survived, but lost my previous capacity for love and happiness.

John Steiner was born in Prague in 1925. His university-educated mother translated Gone with the Wind into German, while his father was employed by the leading private bank in the city. Expelled from his school when he was fifteen because of his “racial” background, John transferred to a Jewish technical school.

The entire family actively resisted the Nazis. John’s mother was interrogated in the Gestapo headquarters in the bank building in which his father had worked. John’s father was sent to Theresienstadt in September 1941. John was sent there in August 1942, in retaliation for the assassination of Nazi security chief Reinhard Heydrich. In November of that year, his mother was also deported.

John was later sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau, as were his parents. His mother was gassed there, and John and his father were sent to the slave labor camp Blechhammer. He resisted his tormenters by keeping up the will to survive, although losing the belief that he actually would.

John’s father was liberated from Blechhammer in February 1945. Just one month earlier, John had been sent on a death march to the slave labor camp Reichenbach. From there, he and hundreds of other prisoners were shipped to Dachau in open cattle wagons.

Only a few – the physically strongest – were still alive after their brutal journey. At the age of 20, John became the spokesman for the small group of survivors, courageously addressing the the SS captain and telling him that he should either shoot them or help them. The captain decided on the latter, and ordered special rations for the group for two weeks.

When John was liberated in April 1945, he was near death. He had suffered severe frostbite and the amputation of the toes of his right foot.

After recovering, he returned to Prague and was reunited with his father. John worked for the government, but because of his work against the Communist regime, he had to leave Czechoslovakia. He went to Australia and then the US where he continued his studies and earned a PhD. John taught at the University of California Berkeley and Sonoma State University, where he founded and directed the Holocaust Studies Center. He authored several books on the Holocaust and entered into a dialogue with former perpetrators resulting in major research on the subject.

Additional stories are only available in the full online exhibition.

Hiding to Survive

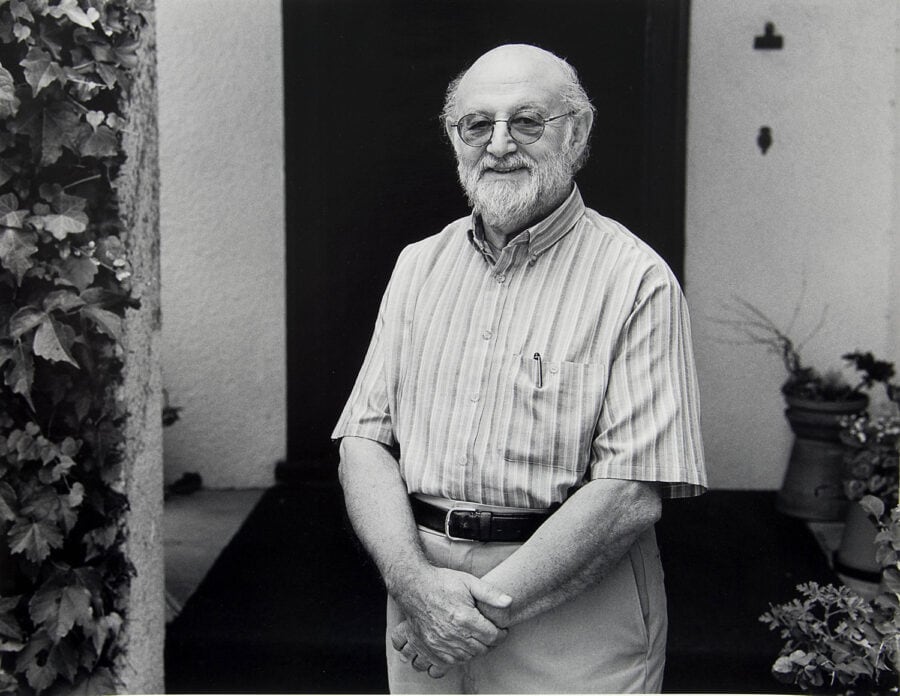

Andre Gabany

After surviving most of the war with false identity papers, Andre Gabany was imprisoned by Nazi sympathizers.

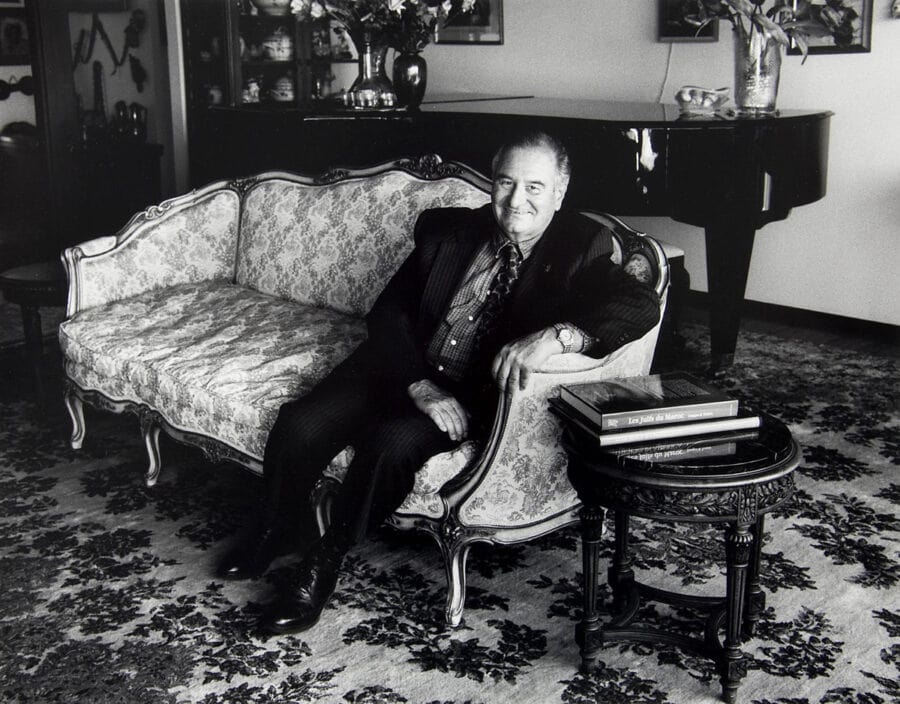

Andre Gabany was born in Debrecen, Hungary in 1930, into a family that included judges, physicians, and business people. At the beginning of the war, Andre’s father and grandfather had been considered “exempt Jews’ because his grandfather was a respected judge. Andre’s father was even inducted into the Hungarian army as a motorcycle messenger.

Andre, his mother, and grandfather lived in Budapest. They moved to Sopron to be close to an uncle who had been educated in Germany. They hoped this connection would help them receive better treatment, but things did not turn out that way. In Sopron, forced to wear the Star of David, Andre was spat upon and beaten by his classmates for being Jewish. The Gestapo took hostages and forced most of the Jewish population into ghettos, and his uncle was deported to Auschwitz. Relatives helped his mother to obtain false identity papers, and a Christian neighbor helped them escape from the Sopron ghetto back to Budapest. From there, they traveled to a small village next to Lake Balaton, pretending to be refugees fleeing from the Russian occupation.

An officer asked me to identify the good and the bad Hungarians, so that he could have the Nazis sympathizers executed. I had absolute power at age fifteen and I had not one person killed.

As the Russian army was approaching, Hungarian Nazis patrolled the area and discovered that the Gabanys were Jews. They were beaten and arrested. While they were being transported westward to Germany, they were liberated by the Russian army.

In prison, Andre met a high-ranking Russian officer. After the liberation, he asked Andre to identify the good and the bad Hungarians, so that he could have the Nazi sympathizers executed. Andre refused to do so.

Andre, together with his mother, came to America in 1948. He attended the University of California and Stanford University. Andre worked as a mechanical engineer and participated in major engineering projects including the first American space satellite and the design and construction of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System. He and his wife Solange, who was born in Casablanca, Morocco raised their family in California.

Of his large extended family, only Andre, his mother, and his grandfather survived the Holocaust. His father had been driven out to a minefield by the Nazis and killed. Most of his schoolmates were deported and died.

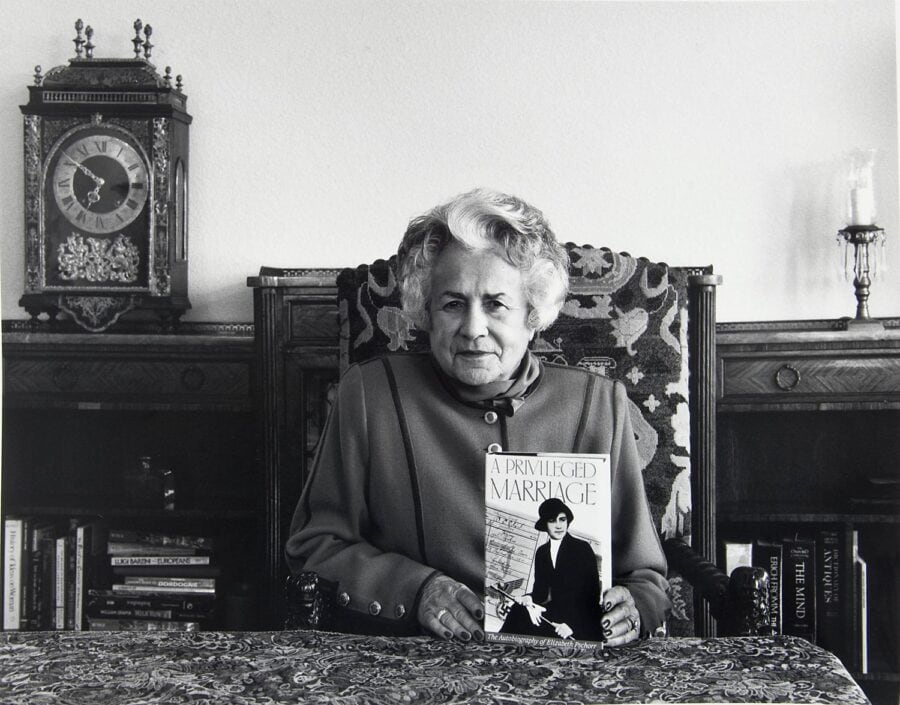

Elizabeth Pschorr

Elizabeth Pschorr was married to an Aryan and survived the war in Germany because of this “Privileged Marriage.”

Elizabeth Pschorr (née Holzer) was born in Hamburg, Germany in 1911. Her mother was a German gentile and her father was an Austrian Jew. Her father felt German first, and Jewish second, and, wishing to save the family from persecution, had the children baptized as Lutheran. Thus, as a child Elizabeth was unaware of her Jewish ancestry. Her first encounter with anti-Semitism occurred when she was about eight years old; her best school friend told her that she could not play with her anymore because she was Jewish.

In 1933, the Nazi party came to power. Elizabeth and her Aryan fiancé, Fritz Georg Pschorr, agreed that their love was stronger than racial politics. Although his family did not approve of his marriage to Elizabeth, the couple decided to remain in Germany and found refuge at the Pschorr family property near Munich, where they tried to live as inconspicuously as possible. Their three children, when born, were baptized. Under the Nuremberg laws, their marriage and the fact that they had children protected Elizabeth to a certain degree. However, she still had to surrender her German passport and carry an identity card stamped with the “J” and the name “Sarah.”

We escaped the destruction of Hamburg by moving to the country and also avoided my registration at the Jewish Center. This was a required act all over Germany and served later for tracing Jews for deportation.

Elizabeth was threatened by local party leaders, who confiscated money and rations. She was desperate and had to find food and medical supplies for the family by begging the neighboring farmers. Elizabeth’s husband was drafted into the army and had to disclose his wife’s identity. He was enlisted in the Organization Todt to do heavy labor, but he fell ill with hepatitis and did not have to serve in the end.

Aided by the organization Joint, the family spent time in a displaced persons camp until they were able to leave for America on a troop transport. Elizabeth wrote a book, A Privileged Marriage, and often spoke to groups describing her wartime experiences.

Louis de Groot

Louis de Groot spent the war hiding in many different cities and with different people in the Netherlands. He was the only one of his immediate family to survive.

Louis de Groot was born in June 1929 in Amersfoort, the Netherlands. He lived with his parents, and his sister Rachel in a spacious apartment above their electrical store in Arnem. On November 16, 1942, a local policeman came into the store; the policeman shared his suspicion that the Germans were planning a roundup of Jews that evening.

The family took the policeman’s warning seriously. They separated, and each went into hiding in a different location. Louis’ parents reminded him that people were risking their lives by opening their home to him. His sister’s last words to the 13-year-old Louis were, “Be strong.”

Because of changing conditions that threatened his safety and increased the risk of discovery, Louis moved thirteen times within the next year. He was helped by a Christian couple, Anne and Dirk Onderweegs and their daughter Bonnette, in whose home he arrived in January 1944.

I am the sole beneficiary of my parents’ brave decision for the family to go into hiding. Every day I thank them for having had the courage to take that step while there were so many unknowns to deal with. They are my heroes.

Louis’ parents went to Amsterdam, a few blocks from where Anne Frank and her family were hiding. In 1944, his parents and sister were denounced and arrested by collaborating Dutch policemen. They were deported to Auschwitz where they were killed.

The Oderweegs treated Louis like their son, and he continued living with them for 16 months after the liberation. In 1946, wishing to return to a Jewish environment, Louis moved to the Jewish Boys’ Orphanage in Amsterdam.

In 1948, Louis volunteered for service in the Haganah, a Jewish paramilitary organization for the founding of the new state of Israel. The following year he returned to Holland and finished high school. He immigrated to the U.S. in 1950, and the following year was inducted into the U.S. Army during the Korean conflict. Louis earned a master’s degree in economics at Columbia University and worked as a business economist with the IBM Corporation. In the U.S., he met his wife Barbara, an artist, who helped him live with his painful wartime losses and to build a family.

Additional stories are only available in the full online exhibition.

The Kindertransport

That first night together we talked for hours, trying to piece together ten years and two worlds.

Both Ursula and Nancy (née Schulz) were born in the free state of Danzig to a Jewish mother and a Catholic father. Although Danzig was still nominally free, it was actually controlled by the Nazis long before its annexation in 1939; Ursula remembered the Hitler Youth storming through the streets and Nazi flags being flown.

The Kindertransport was organized by the Quakers in the months before the outbreak of World War II to rescue Jewish children and send them to England. Nine-year-old Ursula was sent to England on a sealed train in May 1939. Her parents, sister and other relatives came to see her off at the train station.

The first family with whom Ursula was placed spoke no German, and she spoke no English. She was re-assigned to a family closer to her own background. When Ursula set the table there, she placed a German/English dictionary next to her plate and an English/German dictionary next to theirs. Ursula lived in many locations during her ten years in Britain, including the homes of a farmer, a schoolteacher, a coal miner, a salesman, a juvenile parole officer, and at a boarding school. When war was declared, she, together with many other London school children, was evacuated to the south of Wales.

Five-year-old Nancy remained in Danzig with her parents. During the war, she was under strict orders not to tell anyone of their Jewish background, understanding that if she should let it slip, they could be sent away. She often did errands for the family and was sent to the train station to pick up messages. Nancy remembered watching her mother sew jewelry and money into the lining at the bottom of her grandmother’s coat, because she was being sent away to an unknown destination with other elderly Jews. She was never seen again.

After the war ended, Nancy was sent on a Jewish transport to Berlin, where a cousin of her mother’s found her in an orphanage. A few months later, Ursula received a telegram from Nancy with news about the fate of their family. Both of their parents were dead. Their father had been taken by the Russians after their liberation of Danzig and never heard from again. Their mother had died of typhus shortly afterwards. A grandmother, aunt, uncle and cousin had been deported and perished in the camps.

Ursula’s English guardians offered to formally adopt her but she preferred to emigrate to the U.S. to be with her sister. Relatives in California sponsored them, with young Nancy arriving in 1946 and Ursula following in 1949.

Reunited after ten years apart, the sisters began the long and complex process of piecing together their two worlds. They settled close to one another in Northern California where each worked, married, and raised families.

Alan Peters

Alan Peters was sent to England on a Kindertransport.

Alan Peters was born in 1923 in Vienna, Austria. His father had his own business as a cabinetmaker, and the family lived on a quiet street of working-class apartment houses.

In March 1938, the German Army marched into Vienna. Alan was attending high school, but within six weeks, all Jewish students were expelled and had to transfer to new, segregated Jewish schools. Instead, Alan chose to drop out and apprentice for his father unofficially, since Jews were excluded from the official apprenticeship program.

When I was fourteen, the German Army marched into Vienna followed by a motorcade led by Hitler in his limousine. My life and that of my family and friends changed completely.

On the morning after Kristallnacht, November 9th, 1938, an SS officer demanded the keys to the family business and offered to “buy” it for a token sum. Alan’s father and 5000 other Jews were arrested and sent to Dachau. The purpose was to spread fear and encourage Jews to leave Austria.

There had been an unspoken agreement between Alan and his mother that he would not leave Austria without his father. But they felt a new sense of urgency and Alan’s mother urged him to leave now.

The British Government had agreed to shelter 10,000 children from Germany, Austria, and later, Czechoslovakia, and Alan was selected to travel to England with a Kindertransport. Miraculously, his father was released from Buchenwald two days before Alan’s departure on the condition that he leave the country within 30 days. Alan’s father arrived with his head shaved, looking gaunt and scared, but the family was very briefly united.

Alan’s father was forced to leave for Italy alone, and was only allowed to take one suitcase, his wedding ring, and 10 German marks. The war broke out in September 1939, with Alan’s mother still in Vienna and his father in Milan. She was able join him several months later, and the two boarded the last ship to Palestine, saving their lives.

In England, Alan’s sponsors enabled him to attend university, graduating with a degree in engineering. He served as an officer in the British army and was reunited with his parents, who returned to Vienna after the war.

Resisting the Nazis

Resisting the Nazis took many forms. Some Jews and Gentiles joined guerilla groups, while other Jews stood up to guards in concentration camps. All of these acts of resistance – no matter how large or small – could have caused that person to be killed. The stories that follow show just some of the many ways that Jews and Gentiles stood up to the Nazis.

This section is only available in the full online exhibition.

View the Documentary

In this deeply personal film, originally shown on the Sundance channel, you will see Eisen’s portraits of survivors you’ve met within this exhibit and hear their voices describing their wartime experiences. Running time 24 minutes.

The full-length documentary is only available in the full online exhibition.

Continue Exploring

Curriculum Guide

This content is only available in the full online exhibition.

List of Resources

This content is only available in the full online exhibition.

Comment Book

This content is only available in the full online exhibition.

Thank You

Thank you for viewing this exhibit through the MUSEUM.

[Acknowledgements and Other Info Here]

MISSION

To find out more about the MUSEUM, visit THEIR WEBSITE today.

Multiply by Six Million is a project by Evvy Eisen and toured by Exhibit Envoy. Eisen’s work is in private and museum collections in Europe and the United States, including the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC, the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, and the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris. For additional information about the photographer and her work, visit evvyeisen.com. Learn more about Evvy Eisen and this project at evvyeisen.com.

The Multiply by Six Million project was partially funded by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, California Humanities, and the Koret Foundation. The exhibition’s tour is organized by Exhibit Envoy, a non-profit organization that creates and travels exhibitions across California and the United States. This online exhibition is adapted from the physical touring exhibition. All photographs and writings are © Evvy Eisen unless stated otherwise.